On a cold, rainy day in the winter of 1955, a young freelance photographer named Dennis Stock took a few pictures around New York City of actor James Dean, who’d just finished shooting East Of Eden and was about to start Rebel Without A Cause. Stock met Dean at a party thrown by Rebel director Nicholas Ray, and saw him as his ticket out of a string of piddly gigs snapping soirees and red carpet premieres. He convinced the up-and-comer that with his still camera he could tell a story as meaningful as any movie Dean would make—that he could frame him as the complicated artist that he wanted to be. Stock had his liaison at the Magnum Photos agency pitch the idea of a photo essay, “Moody New Star,” to Life magazine, and spent a week chasing a still-skeptical Dean around the city. And then in Times Square, in crummy weather, Stock caught his subject in a long coat, with his collar upturned and shoulders shrugged, and a cigarette dangling from pursed lips.

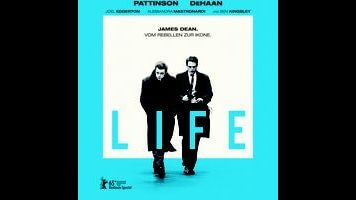

All of the above is in the movie Life, which is director Anton Corbijn and screenwriter Luke Davies’ dramatization of what led up to that photograph—the most famous ever taken of Dean—and what happened in the days that followed. Some of the story comes straight from the historical record, and some of it’s embellished and shaped to offer more of an interpretation of what happened. Davies, who’s probably best known for writing the druggy romantic novel Candy (and co-writing the screenplay for the Heath Ledger movie made from it), does a lot of underlining in Life, usually via the character of Stock, who talks a lot about what Dean means. “It’s like he’s the symbol of a new movement or something,” he tells his Magnum boss John G. Morris, adding, “There’s an awkwardness I want to capture… something very pure. You can’t fake it.”

But while the script is sometimes too heavy footed, on the whole Life has an unassuming quality that wears well over the course of its two hours. Usually, when a prestige-ish movie pops up in December with little fanfare and almost no major festival bookings, there’s something suspect about it. But Life benefits from assured direction by Corbijn, whose years of photographing rock bands like U2 and Depeche Mode makes this project more than a little personal. Corbijn’s unusually attuned to the dynamic relationship between two very different creative types: one a celebrity, and the other trying to take advantage of that fame. And cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen makes masterful use of muted light and deep shadow, burning in Corbijn’s images of a rumpled actor trying to shrink away from his stalker’s remorseless lens.

Corbijn also gets very good and somewhat against “type” performances from Robert Pattinson as Stock and Dane DeHaan as Dean. The latter has the harder job, trying to imitate a well-known young idol who looked more rugged and haunted on screen than DeHaan usually appears. He gets by with it, not straining to be mysterious and gruff, which pays off especially well in the scenes where Dean spends a few happy days with his family in Indiana farm country. DeHaan’s very good at playing Dean’s intellectual curiosity and joie de vivre, even more than his stubbornness and sloth. Meanwhile, Pattinson has shifted easily out of his own “moody new star” years, playing Stock as tentative and desperate—and much more of a man-on-the-make than his subject.

Corbijn’s reserved, removed approach gives his stars the space to develop a real chemistry, which makes their characters pleasant company, once they get past their early clumsiness around each other. Corbijn doesn’t overplay any of the conflict in Davies’ script: not between Dean and his studio bosses (including Ben Kingsley as Jack Warner) or between Stock and Morris (played by Joel Edgerton). But he does seem to revel in the chance to film a replica of 1950s New York, with its imitation Actors Studio and its underlit bars where at any minute Eartha Kitt might drop by.

A lot of Life has to do with Stock’s gradual realization that his own premise was correct. Times really were changing, and Dean wasn’t just playing a role when he said he had no interest in the old Hollywood star system. That’s ultimately what the Times Square photograph captures, with Dean shivering his way past the marquee of a theater playing Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea. Here was the new generation, turning its back on the old. More often than not, Life too freezes that moment in time.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.