James Marsters on Dudes & Dragons, the end of Angel, and having fun with John Barrowman

Although he started his acting career in the theater in the ’80s and popped up in a few TV roles during the first half of the ’90s, James Marsters started down the path to proper stardom when Joss Whedon selected him to play Spike in the TV adaptation of Whedon’s 1992 film Buffy The Vampire Slayer, a gig which ultimately carried him to series-regular status during the final season of Angel. Since then, Marsters has forged a body of work that’s kept him on the radar of sci-fi and fantasy fans—appearing on Torchwood, Smallville, and Caprica—in between guest shots on procedurals like Without A Trace, Lie To Me, and Hawaii Five-0. Prior to the release of his new film, Dudes & Dragons, Marsters spoke to The A.V. Club about his sci-fi and fantasy endeavors, what it takes to make a small-budget film look like a million bucks, and how he thinks he’s been able to escape a genre-only career—not that there’s anything wrong with that.

The A.V. Club: Making a swords-and-sorcery comedy like Dudes & Dragons requires a delicate balance. How did you feel when you were pitched the project? Were you hesitant, or were you just looking to have fun?

James Marsters: You know, the script had an interesting, quirky humor to it, it had its own voice, and it interested me. I think that every author has their own style, and when I read someone who seems to have a new voice, who seems to be telling a story with a new narrative flavor, I get really interested. And Maclain [Nelson] and Stephen [Shimek], who wrote and directed the movie, had that. And the script had that. I don’t know how to describe it, except that when I was reading it, the first 10 or 12 pages I was thinking, “What is this?” And then by about the 20th or 25th page, I was laughing as I was reading it, every page.

I really enjoy movies and books and things like that, which take just a little while for you to catch on to what they’re doing—and then once you click into it, you’re off for a really great ride. I find the Coen brothers’ movies are like that for me. It takes me just a little while. Remember the first time you saw O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and you think, “Whoa, this is not Blood Simple!” And then you just give over to what they’re doing. That’s what I experienced when I read the script, it’s certainly what I experienced when I saw the movie for the first time, and the same thing for the audience. I saw it with a large house, and there were little murmurs of laughter in the beginning, nice little titters, everyone’s paying attention, and then—really quickly—big laughs all the way through. Once the train was out of the station, it just didn’t let up, and everyone had a great time all the way to the end credits.

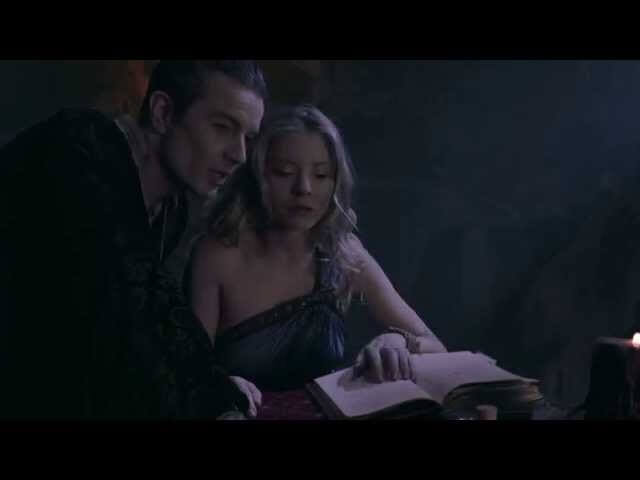

AVC: With Lord Tinsley, how much of the character was on the page, and how much did you bring to it by virtue of your villainous gravitas from the past?

JM: [Laughs.] Well, let’s see: good acting is not messing up good words. I always say that an actor is the waiter and the writer is the chef, and it’s the actor’s responsibility to take the food from the kitchen to the table without dropping it. If you can do that, they’ll make you look really good.

What I saw in my mind when I read the script was a really ruthless bastard, a powerful wizard, but a frightened child underneath it all, so he can really be kind of adorable at the end of the day. Even though he was doing a lot of damage in the world, there was something cute underneath, which I think is important for a comedy villain. It’s a little different from playing a villain in drama. Because I think that the villain should be a little accessible and a little bit vulnerable and a little bit laughable.

AVC: It may not have had a massive budget, but whatever they had to work with, they certainly made the most of it visually.

JM: That’s something else that I’m so excited about. I used to produce theater in Chicago and Seattle, and I firmly believe—let’s say we had a budget of about $7,000 per production, and we had to cycle through our shows every four weeks, because our subscription base was small, and we didn’t have enough people to come see each play for more than a month run. [Laughs.] But what I heard from critics and some audience members, especially when we got really going in Seattle, was that our shows were just as entertaining as the Seattle rep, as the Intiman Theatre or the bigger houses that were spending, let’s say, a quarter-million per production. I firmly believe that you can do that. If you really know how to tell a story and you know what’s important, you don’t have to throw money at it.

Furthermore, what I discovered was that if you don’t need money, you’re not beholden to anyone, and you can tell whatever story you want in the way that you want to do it. I remember we were doing Peter Weiss’ play The Interview, which is basically just the Nazi war crimes trials of Frankfurt, Germany in 1945.

AVC: So the feel-good hit of the season, then?

JM: Well, it’s this holy grail for artistic directors: Everybody wants to do it, but nobody can talk their board of directors into it because it’s very risky. But we just did it. And I remember being at parties, and all the big-time directors and artistic directors who were my friends and who had hired me as a director were asking me, “How did you talk your board into that?” I said, “I don’t have one. I just put up $7,000 and just did it. Ha ha!” [Laughs.] They were so jealous. I was free! I was free, because I didn’t have to talk any investors into doing what I wanted to do. So I have a soft spot in my heart for independent film and for people who can get a lot down for little. I think it takes real creativity to do that, and I am just blown away with what Maclain and Stephen have been able to do with the money they had.

We shot the whole thing on green screen! The only thing I saw when we filmed it was a couple of rocks and a couple of props and maybe two or three chairs. That was it! Everything else, they said they were going to build on the computer. And I kind of thought, “Well, that’s cute, but there’s no way you’re going to be able to afford to do that. You guys are very ambitious, and I’m really having fun working with you, and the other actors seem to be awesome…” But I really thought, “Well, the jury’s really out on whether you’re going to be able to achieve this.” And they went away and started cooking, and they didn’t give up. And they knew how to spend money, which is that you really try not to. [Laughs.] And when they finally came and said, “We’re ready for you to see it,” and I watched it, I was blown away.

The thing is, the audience has to want to buy it, if you know what I mean. If an audience doesn’t want to buy computer effects, if something’s false about the performance or the script, or if there’s something that’s not charming about that, you don’t want to believe it. And it doesn’t matter how much you put into the computer effects, because they’re just not going to go for the ride. But if you charm them, if you interest them, they’ll go along with it, even if it’s not as visually believable. I think that’s kind of the key to computer effects. [Laughs.] But they did a very good job. Everything looks great. The computer effects are not the latest generation. They probably were first generation three or four years ago. But it’s a digital release, it’s meant for smaller screens, and I think when people watch it, they’re just going to be laughing and enjoying themselves and not picking everything apart.

That said, there are a lot of people who are going to watch this on their computer screens, and they’re just going to say, “Wow, that’s a great movie!” They’re not going to be aware that it’s not a big budget film. They’re not even going to think about it. Actually, I should’ve lied to you. I should’ve claimed that it was a $70 million picture. [Clears throat.] In fact, I, uh, don’t know what you’ve heard, Will, but that was a $70 million picture, and they spent an incredible amount on the special effects. So get your facts right, man! [Laughs.]

AVC: Something that’s fascinating about your career is the way you made your mark through Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Angel, a pair of series that still have an extremely devoted following, yet you didn’t really find yourself locked into playing the same character over and over again.

JM: Well, when Buffy and Angel stopped, the question was, “Do you want to remain blond and British?” And I had an agent that actually said, “Look, if you just want to claim to be British and keep bleaching your hair, there’s work there, man.” And I thought that that would be really stupid. [Laughs.] Like, how pathetic is that? A guy from California going into auditions, claiming to actually be from Britain.

AVC: “’Allo, mate!”

JM: [Laughs.] Yeah! [Affects British accent.] “No, truly, I’m from Britain. No, I’m from West Hamfordshire, seriously. I just love your work.” It was just kind of too laughable for words. Also, the kind of roles that that would’ve gotten me would’ve been drug dealers, rock stars, and other vampires, I think. So once you ditch the accent and ditch the hair, you kind of start from zero, and you’re not really that same product that you got famous for.

So it’s a double-edged sword, but I think it’s worked out really well. People are aware that I did Buffy The Vampire Slayer, they’re aware that I played Spike, so they take a look. But they can’t have that Spike thing going on, so I’ve got to do something else. So, yeah, I think it may have been less money in the short term, but I think it’s a longer career choice just to show people my own hair color!

AVC: So what was the process of building Spike? Joss Whedon obviously brings a lot to the page from the get-go, but how much were you able to help build the character yourself?

JM: That’s something I’m a little less aware of. Another actor was asking me about this—“What’s your process?”—and getting specifically into that. I’d done probably 100 plays before I came down to Los Angeles, and a lot of this stuff is, at least in my experience, just exploring and playing.

What I will say is that we had three days between the time that I got cast and the time I was filming the character. They had hoped to find someone more famous for Spike. They had hoped to find kind of a “name,” and they couldn’t find what they were looking for. And Joss basically told casting, “Scrape the bottom of the barrel and just call in everybody that we wouldn’t normally see. We’ve got to find someone. We’ve got our backs up against the wall, I’m going to kill this character after five episodes anyway… Find anybody who can do the accent!” And at the bottom of the barrel was li’l James Marsters! [Laughs.] So because there was a time constraint, there wasn’t a lot of complexity.

I’ll also say that I had just moved down from Seattle and I was very lucky that I had just done a production of Macbeth that was really successful. I was playing the title character, and to do that, I had to get comfortable with the idea that I would have fun killing somebody. And that took a long time. Luckily, in stage, you have—or at least we had—six weeks to rehearse it, so I had six weeks to wrap my mind around playing somebody whose job it is to repeatedly kill people, and he really doesn’t mind. In fact, he kind of likes his job. And I found out that that’s actually the thing that trips up warriors more than anything: The moment of murder is actually really oftentimes very fun. There’s an adrenaline rush and a sense of power and control that one naturally feels, and you end up spending the rest of your life feeling guilty about feeling that way.

I’d already kind of experienced that, so when I auditioned for Spike, I noticed that one of the main things is that he’s having a blast being a murderer. It’s important to have fun when you’re performing. Where I come from, they say, “It’s called a play for a reason. It’s not called a work. Nobody’s going to pay money to watch you work.” So you have to have fun up in front of an audience or in front of a camera.

The other thing is that Joss wanted me to be “the Sid Vicious of the vampire set.” And I know enough about punk rock that I went to Joss and said, “You don’t want Sid! Come on, Sid was an idiot! Sid couldn’t play bass. Sid didn’t play on Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols, man. He barely toured. He was pretty, but…” This is Sid. [Starts talking laconically, with a British accent.] “Girls like me because I’ve got a nice face and a good figure.” [Laughs.] I mean, Sid was not the sharpest tack, no disrespect. What he wanted, I was hoping, was Johnny Rotten, or John Lydon. He wrote the songs, he was the singer, he was the frontman, he was the driving force… Well, Steve Jones was a driving force, too. Anyway, I told him, “I think I’d rather try to give you Johnny Rotten.” And he kind of rolled his eyes, like, “Whatever, kid: just punk rock, all right?” “Yes! Okay! Got it!”

They tried to dye my hair black, like Sid’s, but it didn’t really look good with my skin. At that point, the hairdresser just kind of looked at me with pity and said, “I’m so sorry, but we’re going to have to bleach you. I’m so sorry!” [Laughs.] So they started bleaching me, and if you know anybody man or woman who has really bleached blond hair, just give ’em proper respect, because it’s not the easiest thing to go through.

The only other thing I remember about thinking about playing Spike was stealing a bit from Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner. It’s kind of a way that Rutger Hauer was talking to his minions that I really ripped off. It’s kind of a calm, eerie quality that he had that I just tried to keep in my mind. And there was a way that Malcolm McDowell walked when he was in Cat People. Not a good movie, but it’s a really good performance. He just had this feline predator walk that I thought was really fucking cool.

AVC: How tired did you get of people suggesting that you were inspired by Billy Idol?

JM: Well, that was the joke: “He wanted a Sex Pistol, and he got Billy Idol!” [Laughs.] And there’s nothing wrong with Billy Idol, you know? Billy’s awesome. And he’s still rocking, by the way. Someone told me they saw him live not long ago, and he still rocks. So I’ll take it, man. Billy Idol? Sure!

AVC: Angel ended far more abruptly than certain viewers would’ve preferred. Were you as bummed as they were, or did you feel like it was as good an ending as could’ve been managed under the circumstances?

JM: No, we were all bummed! Because we were so proud that the show was doing well. That last season, the audience almost doubled—I think it went up by 80 percent—and we were all riding high, we were all full of ourselves, and we were all thinking, “There’s no way they’re going to cancel us now! Ha ha ha ha ha ha!” And then life happened. [Laughs.] It was, like, “Nope! You’re gone!” And the problem was that Joss likes to plan ahead, and this one caught him completely by surprise, so he hadn’t saved any budget or built up a storyline to finish the arc of Angel.

Angel is all about regret and making up for the damage that you do early in life, metaphorically speaking, and trying to grow out of that and heal from that and be better. So if Angel starts as a villain, the end of his arc is true hero, and how do you accomplish that with absolutely no money saved at all?

I think Joss’ idea was that Angel and his friends are up against a battle that they’re not sure that they’re going to win, but they’re going to go out swinging. They’re going to try anyway and sacrifice their lives, most likely, but they’re still going to do it. And yet he could only afford one quick computer-generated shot of hell opening up and evil dragons and other winged creatures coming out of this rift in space. The rest of it, he just had to film our faces looking grim and manly, hopefully. And that’s the best we could do! [Laughs.] So we were freaked out! We were, like, “What are we going to do? We’ve got nothing!”

To his credit, a lot of shows get canceled abruptly, and there is no attempt to bring it to a thematic conclusion. And I think Joss pulled one out of his hat right there and gave us one anyway.

AVC: It’s been reported that you had way too much fun working on Torchwood.

JM: [Laughs.] How can you not? How can you not have fun when you’re working with John Barrowman? He’s one of the kindest, most supportive, most professional, and most insane people I’ve ever worked with. You’ve just got to give over to him. It’s like being on Space Mountain: You’ve just got to throw back your head and laugh and enjoy the ride.

I had an absolute blast. The entire cast was very professional and very kind and willing to risk. I can have the most fun when I feel safe, and when I feel like everyone around me is working hard and trying to make it really good, and at that point you can just release. And I got to kiss a guy and then beat the crap out of him. [Laughs.] That was awesome!

I’m a subversive artist by nature, and when I had a theater company, a lot of our shows were about subversion. Subversion is not about making people angry on purpose, it’s about divesting the audience’s lies they get taught in childhood, and some of these lies can be “violence works,” “you can buy yourself identity,” “you can buy Christmas,” “old people are boring,” stuff like that. When I met Russell T. Davies, who did Torchwood and the first few seasons of Doctor Who, he said that he wanted Torchwood to be his Buffy. And I didn’t quite understand what he meant by that, but as I got into it, I understood: Buffy was subversive in its day because it was taking after the lie that women can’t defend themselves, and Torchwood was taking after the lie that gay people can’t be heroes. And because it was subverting that, it was offending all the right people. And it was something that makes me just too happy to be a part of. “Oh, I’m sorry, are you uncomfortable? Well, watch this!” [Laughs.] So, yeah, I had a blast. An absolute blast.

AVC: You’ve been playing both sides when it comes to comic-book characters. On the Marvel front, you’ve voiced characters in two different Spider-Man animated series as well as Mr. Fantastic in The Super Hero Squad Show. Meanwhile, over on the DC side of things, you played Brainiac on Smallville and voiced Lex Luthor in Superman: Doomsday and DC Universe Online.

JM: I’m just super lucky. I don’t know how else to explain it. I just keep trying to have fun when I’m doing stuff, and people keep calling. You know, with Brainiac, my brother was more into Superman comics, and I was more into Batman comics, because I always felt like, “If Batman goes to work, he might get shot, and if he gets shot, he might die!” So it was inherently exciting to watch Batman go to work, whereas Superman, you know he’s going to be fine, so how do you get that character into a real adventure if his life is never forfeit?

And what I thought was genius about Smallville was that it took Superman before he was a man, before he knew he was super, when he was a teenager, so he’s therefore vulnerable every day. Not to the thing that we’re used to seeing him vulnerable to, but to family, to friends, to grades, teachers, girlfriends, self-identity. What freaked me out about Brainiac in the comic books was that he always had this maniacal smile, which I’d never seen on a robot before and which made me feel very uncomfortable. But on the TV show, that wasn’t in there so much. And I remember a scene with Tom Welling when he was in his Fortress Of Solitude, and it wasn’t written, but I thought, “Oh, this is my chance! This is my chance to get that maniacal, crazy smile.” So I kind of snuck it in there, straight from the comics.

I did kind of a Hugh Hefner-esque Lex Luthor voice for Doomsday, and they liked that a lot and called me in for the video game. And I started doing that version of the voice, and after about a minute, the director just said, “James, could you come into the booth? We want to show you something.” So they showed me the drawing of the character that they were doing, and this Lex Luthor was not just this cool guy in a suit, this guy was in battle armor, with rocket launchers on his shoulders. And then they said, “Yeah, we’d like you to beef it up a little bit.” I said, “Oh. Yeah, okay, I can see that.” [Laughs.] So I started just going off. [Growling.] “I will destroy you, Superman!” And that worked out really well. In fact, I’ve been doing that for years. They just had me back in the booth to do some more downloadable content for the game, and it just keeps rolling, so I’m having a blast doing that.

AVC: You’ve managed to find your way into a number of sci-fi franchises: You’ve done a voice for Star Wars: The Clone Wars, and then a year or two after that, you found your way into the Battlestar Galactica universe via a recurring role in Caprica.

JM: Yeah! Oh, man, that was a wonderful experience. I loved Battlestar Galactica. I thought that was so good. And it was such an exciting idea to show a world that the audience knows is about to blow up and the characters don’t, and you just get to watch this inevitable unraveling of society. Which seems like kind of a hard sell, and thematically it’s a little depressing. [Laughs.] Because it’s kind of a warning for us now on Earth: Are we marching toward oblivion, and how aware are we of our demise? I don’t think that it’s a guarantee that our own world is going to stop, but I think it’s a good thing to worry about.

You know how they say that if you put a frog in some water and bring it to a slow boil, the frog won’t leap out because it doesn’t realize it’s happening because it’s so slow? [Laughs.] That’s the kind of metaphor for Caprica that I think is applicable to the world now. The great thing was, they were so talented—because it was the same team that did Battlestar Galactica—and they were so tight working together as a crew. They would get seven different camera angles in one take, which—technically speaking, as far as lighting that and making room for all the cameras and focusing all those cameras—the degree of difficulty of doing that is just astronomical. I’ve seen lighting directors and cinematographers just lose it over having to accommodate two cameras. And they were doing seven! It was just jaw-dropping.

And what that meant was that you’d do one take, and they’d have the wide angle, they’d have the close-up, they’d have all the different angles they needed in that one take. And then the director could come to me and say, “Okay, we got all of that. Now let’s do a completely different take. Last time I wanted you to be furious. Now I want you to be understanding and loving and just absolutely different. I want you to switch it up!” It was incredible. It was so much fun. It was never trying to recreate what had been done before. We were always experimenting to see what might work now, and that was just glorious.

AVC: Is there any franchise or universe you haven’t ventured into yet that you’d like to take a shot at?

JM: Harry Potter? [Laughs.] I don’t know, man. There are so many universes. Every author has their own universe inside their head, and there will more invented. I look forward to getting into as many as I can!

AVC: You’ve done a bit of writing yourself: You’ve penned a few graphic novels within the Buffy-verse.

JM: Yeah, and I recently wrote a comic for Dark Horse where I wanted to return Spike to the underdog status that I think is where he works the best. I think Spike is the best when he’s getting his butt kicked, frankly. And I wanted to write a story where he finds a girl but loses the girl, and he tries to be a hero, but he has his butt handed to him by the villain. But I wanted it to have a happy ending, in that he figures out how to get a new pair of shoes without paying for them and without hurting anybody and without having to get a damned job. [Laughs.]

The question for me was, once Spike has a soul, how do you continue that journey where he’s kind of reclaiming his soul without retreading Angel? Because Joss already did that brilliantly. So I thought, “Well, if Angel’s journey was always epic, and he was always kind of sipping port wine in a mansion in front of a large fire and stuff like that, it would be fun to go the opposite way. If Spike can’t hurt anybody to get a meal, and he can’t steal anything to get a new pair of shoes, well, maybe he’s homeless. And maybe he’s starving to death. And he can’t figure out how to be a good person and survive. So the happy ending was just that he makes the first small step to figuring out how to exist in the world with a soul. And I think it came off pretty well. I was really happy with it.

AVC: Well, you might not have made into the world of Harry Potter, but on the magic side of things, you’ve narrated all of the audio books for the Dresden Files novels and you had a recurring role on Witches Of East End. In the what-might’ve-been column, though, there’s the pilot for HBO’s The Devil You Know. Looking at the people involved, it seems inexplicable that they opted not to pick up.

JM: Oh, my God, yeah. Jenji Kohan created it, with Gus Van Sant directing. We were sure we were going to get picked up! [Laughs.]

As soon as the dailies came in to HBO, they couldn’t say enough. “These are the best dailies we’ve ever seen!” Everybody was so excited about it. And I think… [Hesitates.] I don’t know why it wasn’t picked up, but I do know that if it would’ve been picked up, it would’ve been very controversial, even for HBO. There was a lot of sexual content, but I think that HBO is used to sexual content that’s kind of exciting or titillating. And this was Gus Van Sant, and he cuts a little deeper than that. And the sexual content on this project was unsettling. It all made a point. There was a purpose to it all. But it’d make you squirm. And it’s possible that to read a script is one thing, but to watch people do it makes it more intense, and I think maybe HBO just said, “Ah, I don’t know. This may be too much even for us.”

It was the most fun I’ve ever had in my life while being hypothermic. [Laughs.] Because we did it in Massachusetts in the wintertime, and it was brutally cold. We were freezing! I went to Jenji one time when she was in a tent, watching on a monitor, and I poked my head and I just said, “Jenji, thank you for this experience.” And she looked at me funny, and I would love to see her again and explain to her that I wasn’t being sarcastic! Because we were all dying in the cold, and I think she thought I was saying [Snarls.] “Thanks a lot, Jenji!” But it was an honest statement: I was happy to be there.

AVC: Beyond your theory about the sexual content, do you think HBO’s failure to pick up the series could’ve had anything to do with Salem, which trod similar ground, having premiered on WGN in the interim?

JM: I don’t know, man. I’m not in those rooms. [Laughs.] But I can tell you that it would’ve been so different from that project. Like, we didn’t wear any makeup. There was no makeup on The Devil You Know. I think Salem is kind of very glamorous, and ours was absolutely the other way: hyper-realistic, but with amazing lighting so it looked like a painting. It was very different.

AVC: Not to dwell on projects that didn’t pan out, but you also did a pilot for Syfy called Three Inches that they passed on, although they did at least air it.

JM: Yeah! That was a cute script, man. One of my favorite cartoons was The Tick, and this was about a group of people who had superpowers, but they were very small. The lead character could move any object with telekinesis, but he could only move it up to three inches, and there was one character whose superpower was that he could stink things out really bad, the idea being that even with that amount of power you can really change the world and help people. I thought it was a really fun idea. But there was another project for the network that was a team of superheroes that had big powers [Alphas], and they went with that one at the end of the day.

Three Inches was a fun project, though. And one of the producers on that [Harley Peyton] hired me for another series, one that only ended up running for one season, but it was called Wedding Band. That was a blast: I got to play a Roger Daltrey type of character, a guy who’d been a huge rock star and was still enjoying it. That was fabulous.

AVC: In the midst of all of the fantasy and science fiction, you actually did something that was science non-fiction: You played Buzz Aldrin in History Channel’s Moonshot.

JM: Yes! I’m a science geek, a science fan, so when I meet someone who’s a scientist—and I often do—I geek out. [Laughs.] I’ve met someone who helped design the Mars Rover, I met the person who works at the Large Hadron Collider, the particle accelerator in France and Switzerland, the largest machine built by human beings, and I always geek out. So getting to play Buzz Aldrin was amazing.

The director explained to us that the purpose, what we were trying to achieve, was to show the mission as it really happened. His idea was that when NASA is filmed, because cameras are very large, you have to make the capsule very large, and it always kind of looks like Star Trek, with room to walk around. In fact, it was a very cramped atmosphere, and it was a very dangerous mission, fraught with peril at all times. The thing is, when you listen to the astronauts communicating with ground control, they’re very professional. They’re all fighter pilots, so their voices seem very calm when they’re talking about what’s going on, but in fact it’s life and death. Often death could be imminent, and most people are not aware of how dangerous it was.

NASA only gave it a 50/50 chance that the astronauts would make it back alive when they landed on the moon the first time, because the walls of the lunar landing module were only as thick as three sheets of aluminum foil. If any of them would’ve bumped the wall, it would’ve depressurized, and they would’ve died. When they were landing, the telemetry wasn’t lining up, and what was supposed to be an automatic landing ended up having to be a descent controlled by Neil Armstrong. And when he finally landed safely, he only had 10 seconds of fuel left. Because the telemetry wasn’t working, they overshot the mark. They were planning to land on a nice, safe, flat area of the moon, but because they overshot it, they ended up in one of the rockiest, most dangerous places to land.

When they tried to get back off the moon, they had broken one toggle switch—while they were getting either in or out of their space suits, someone bumped the switch—and that switch was basically the one that, when you flip it, you blast off. That’s the switch that was broken. They were going to die on the moon unless they figured out how to fix that, but as it happened, Buzz had borrowed a felt-tip pin from Michael Collins, who was the third astronaut, orbiting the moon and waiting for them to come back up. So he could stick that pen in and not short out the circuitry, like a ballpoint pen would’ve, and once he got that in there, he could press the button inside the console. If he hadn’t had that pen, they’d still be up there. And they’d be dead.

There were just so many close calls. That’s not even all of them! So it was a dangerous mission. And the director said, “You’re not going to be comfortable. I want to prepare you guys. We want to show that this mission was not comfortable, and that you had to bring it on this mission. So as actors, we’re going to put you through it.” But everybody was on board with it, and it was fabulous. And when Buzz Aldrin saw it, he said, “That was great. Finally it looked like the mission. That film actually looked like the mission.” And I think that’s the highest compliment an astronaut can give you.

AVC: Circling back to something we touched on earlier—you obviously do plenty of genre stuff, but you’ve also had arcs on Without A Trace and Hawaii Five-0, so you clearly can get high-profile gigs that are non-genre. It must be nice to have that luxury to bounce between the two.

JM: Well, look, I enjoy the genre stuff. I love it. But I’m a greedy actor: I want to do everything! [Laughs.] I think all actors do. I’m just very fortunate to be able to do lots of different types of projects.

But I remember talking to David Fury once—David was a writer/producer on Buffy, and he was working on 24 at the time, but he also did Lost—and I was, like, “Are you having fun over on 24? It’s such a hit!” And he said, “Yeah, it’s great, but sometimes I get frustrated: I just want to write a demon to burst through a wall and rip someone’s head off, and I’ve gotten constrained by the real world.” He was working on this project where there are threats of nuclear annihilation and people running constantly, an exciting project, but after Buffy, he felt like it was a little tame. [Laughs.] So there’s something kind of wonderful about having the freedom that fantasy and sci-fi give you to do what you want.

But I’m going to take my life as it comes. And I hope I can continue to do projects of all varieties. But if they all end up being sci-fi and fantasy, that’s good, too.