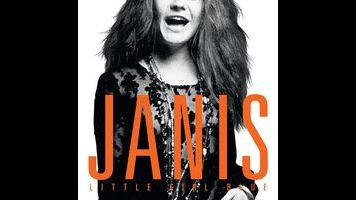

This past summer, Asif Kapadia’s documentary Amy served as a kind of “What happened?” postmortem for anyone looking to understand how fame, drugs, emotional damage, and tabloid shamelessness conspired to kill an uncommonly talented woman at age 27. And now here comes the prequel. Amy Berg’s Janis: Little Girl Blue is about another R&B-loving force of nature who died at 27, consumed by her addictions and by the intense demands on her time. Berg doesn’t have the wealth of Janis Joplin footage or previously unheard music that Kapadia had for Amy Winehouse. But it’s remarkable how similar the two movies are, in terms of the stories they tell about women who came from hard circumstances and developed public images that were hard to live up to. It’s almost like there’s something archetypal about the rise and fall of a certain kind of rock star.

What Little Girl Blue does have going for it is some of the most fiery rock ’n’ roll performances ever captured on film. Joplin may have been a mess off stage (okay, scratch the “maybe”), but she craved the spotlight, and knew what to do when the cameras were pointed her way. Some of the most fascinating material in Berg’s documentary has to do with the singer’s commercial ambitions, which led to her gradually taking over and then abandoning the more mellow, communal collective of hippies in her first band, Big Brother & The Holding Company. Little Girl Blue reconstructs the circumstances behind Joplin’s breakout performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop festival—and subsequent 1968 D.A. Pennebaker documentary—which came about only because Big Brother’s frontwoman overruled her bandmates’ decision not to be filmed, and demanded a second set at the fest to capture her properly.

Berg tells these stories with the help of just about every significant surviving chunk of Joplin’s old TV and film appearances, from The Dick Cavett Show and The Hollywood Palace to Festival Express and Woodstock. She’s also tracked down dozens of people who knew the singer personally: musicians who shared stages with her, men and women who shared beds with her, and family and friends who witnessed her awkward coming-of-age in a Texas small town where she was bullied for being eccentric and mannish. Some of the best insight comes from Joplin’s brother and sister, who speak eloquently about watching her blossom from afar, while also seeing their parents’ embarrassment over a daughter who was a hero to the counterculture they despised.

Little Girl Blue also relies on Joplin’s correspondence with her folks, read in voice-over by the musician Cat Power. There’s a striking, counterintuituve disconnect between the public Janis and the private Janis—with the former more open and vulnerable than the young woman who faked happiness in her letters to try and make her mom and dad proud. It’s at once charming and heartbreaking to hear Joplin apologize for moving back to San Francisco to follow her dream (rather than staying in Texas and studying to be a schoolteacher) and to see her sending news clippings and photos back home from California, as though trying both to reassure her family and rub her success in their face.

This isn’t the first time Joplin’s had a movie made about her. Howard Alk’s 1974 documentary Janis contains a lot of the same performance and archival interview footage, presented without Berg’s shaping and context; and Mark Rydell’s Bette Midler vehicle The Rose is a lightly fictionalized account of Joplin’s final months, right down to her destructive lesbian affair, her stabilizing boyfriend, and her awkward Texas homecoming. Comparatively speaking, The Rose is the best of the bunch, if only because its interpretations and meanings are more open. By contrast, at every turn the interviewees in Little Girl Blue speak bluntly about who they thought Janis was, and why she couldn’t handle success.

But for anyone who just wants “the Janis Joplin story,” told from start to finish—with plenty of examples of why anyone should care about the untimely death of a substance-abuser—Little Girl Blue is the way to go. Far too few posthumous music docs delve into the particulars of what made the greats great, because they’re too busy dwelling on the decadence. But Berg has plenty of actual analysis and appreciation here, showing how Joplin applied her love of the blues and her raspy howl to the untamed sounds coming out of Haight-Ashbury, creating a style that the pop establishment had to take seriously. Whenever the story starts to drag, Berg cuts to a scene like Big Brother’s era-defining performance of “Ball And Chain” at Monterey, which had even Los Angeles’ prematurely jaded rock superstars gaping in justified awe. They knew they were watching something explosive, in a package too fragile to contain it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.