Jason Schwartzman goes tragically toxic in the great Listen Up Philip

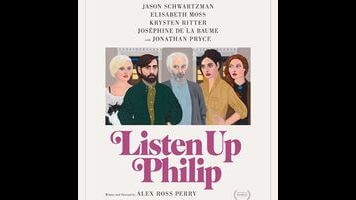

A triumph of composition and organization, Alex Ross Perry’s third feature, Listen Up Philip, tracks three creative types—a novelist, a commercial photographer, and an aging literary icon—across three seasons spent in, around, and as far away as possible from New York. In lieu of a hip, urgent now, Perry constructs the movie in a novelistic past tense, employing a third-person narrator and a very cool jazz quintet score to wrap everything together. He also uses endpoints—of romances, creative phases, and friendships—as starting points, which gives Listen Up Philip the structure of an extended epilogue.

It’s a movie of aftermaths—yet it crackles with a sense of immediacy, the handheld camera pushing its way into tight emotional spaces, framing the actors in revealing and unflattering close-up. Aside from James Gray’s The Immigrant, no other movie released this year has a richer relationship with its characters. It’s generous, but completely unsentimental. Its world is a present day composed of carryovers from decades past, captured on a grainy 16mm stock that has all the textural qualities of Arches paper, with every diffuse light source rendered as a watercolor stain.

But, the thing is, Listen Up Philip is a comedy—a howlingly funny black comedy with really sharp teeth. It plays like a how-to guide for destroying relationships, alienating acquaintances, and undermining any and every conceivable social interaction. The ill-advised entrances are perfectly timed, the asides are impressively insensitive, and the patronizing gestures ooze entitled resentment. Perry likes to place his protagonists into no-man’s-land scenarios, where they can behave as badly as they want, either because they’re already disliked by everyone else in the room or because they’re in an environment in which their worst tendencies are tolerated. He also has a knack for relating to unlikable characters; he singles them out for their meanness, their obliviousness, and their narcissism, but then sympathizes with them.

Listen Up Philip begins where most stories about young artists end. After years of struggling, Philip Lewis Friedman (Jason Schwartzman) has completed and sold his second novel, which will pave the way for a successful literary career that will eventually turn Philip into one of this country’s most respected writers. (The narration, read by Eric Bogosian, occasionally refers to events in the characters’ pasts and futures, which has the effect of making an already diverse, expansive narrative seem even bigger.) After chewing out his college ex for showing up late to a catch-up lunch, Philip goes on a tear. He immediately arranges for another college friend to meet him for an afternoon beer, just so he can give him an unwarranted dressing-down. Having experienced a modest rush of guilty pleasure, he begins to seek out people to slight.

Listen Up Philip has a tricky relationship with its title character. On the one hand, he’s a profoundly shitty person who mistreats other people whenever he thinks he can get away with it; on the other, he’s a tragic figure, incapable of changing or of ever really understanding his own actions, because he never tries to understand their effect on others. Listen Up Philip is about different kinds of individuality, with Philip’s toxic narcissism on one end of the spectrum and the self-determination of his girlfriend, Ashley Kane (Elisabeth Moss), on the other. It’s also about the way people color each other, and how others shape our perceptions of ourselves.

There’s a case to be made that Ashley is the real protagonist of the film; she is, after all, a more dynamic character, and Philip disappears for a large chunk of the movie’s middle third, turning her into the de facto lead. She’s capable of changing her circumstances, while Philip is enabled—and trapped—by his. Perry’s previous feature, The Color Wheel, was a caustic, eccentric road comedy bubbling with undercurrents of claustrophobic psychodrama. Similarly, Listen Up Philip is a comedy about male narcissism that could easily be inverted into a feminist drama; it turns a familiar sad-sack question—“Why do girls date assholes?”—into something like an existential query.

Philip isn’t the movie’s definitive narcissist. That dubious honor belongs to his idol, the vaguely Philip Roth-like Ike Zimmerman (Jonathan Pryce, giving what might be the finest performance of his career). A montage of perfectly spot-on mock first-edition covers à la The Royal Tenenbaums introduces the viewer to Ike’s vast oeuvre, including such classics as Madness & Woman and The Audit, and his very telling failed attempt at expanding his range, A Woman’s Perspective. Ike proposes the younger writer use his country home to work on his next manuscript—an offer he makes without bothering to notify his daughter, Melanie (Krysten Ritter), and which Philip accepts without consulting Ashley. In some ways, Philip and Ike are different versions of the same character, with Ike functioning as a vision of what Philip will eventually become: respected, creatively fulfilled, and completely incapable of recognizing how needy, lonely, and pathetic he is.

Listen Up Philip is orchestrated around absences: Philip’s disappearance from Ashley’s life; his lack of a social filter; the lack of anything resembling affection in Philip’s later relationship with French lit professor Yvette Dussart (Joséphine De La Baume); Ike’s emotional detachment from Melanie. Also notably absent is Philip and Ike’s writing; the viewer never learns anything about their work aside from the titles of their novels (Philip’s breakthrough is the ridiculously oblique Obidant) and one line of rejected prose read by the narrator toward the end of the movie. Perry’s interest seems to lie less in the act of writing, and more in the lifestyle and expectations it creates. Writers are expected to be difficult and solitary in a way other artists aren’t; Philip even goes out of his way to cultivate the proper level of mystique. When a contemporary and literary competitor commits suicide, he reacts as though he’s been outfoxed.

Writing pithy wisecracks is easy. What Perry does is write banter that reveals his character’s insecurities and weaknesses; the jokes they crack become jokes about their own snobbishness and egoism. There’s a level of criticism at play in the film, which immediately sets it apart from similarly set New York art-world horror stories, but it doesn’t cancel out the writer-director’s clear empathy for his characters, who never quite manage to empathize with each other. This sort of mature perspective is a rare thing, and Listen Up Philip establishes Perry as a major talent.