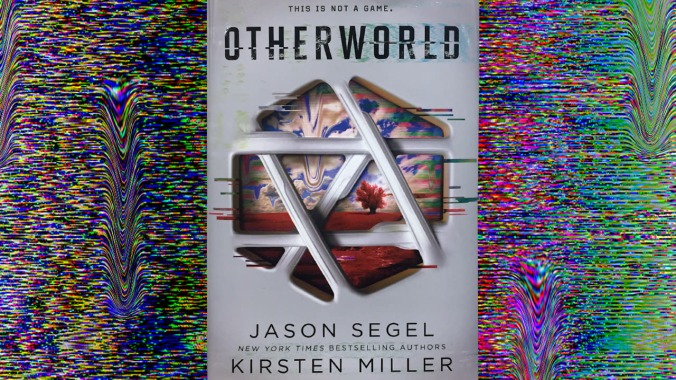

Jason Segel and Kirsten Miller craft an engaging VR cautionary tale in Otherworld

Jason Segel may be best-known for playing Marshall in the long-running sitcom How I Met Your Mother, but it turns out acting is only one of his talents. He’s also a songwriter and a screenwriter, having penned movies like Forgetting Sarah Marshall and The Muppets; and now he turns his pen toward the world of YA fiction. He and novelist Kirsten Miller have already created a middle-grade series called Nightmares! And now, for the slightly older set, they’ve crafted a series based on an immersive, all-encompassing virtual reality game called Otherworld.

Segel was inspired by a VR demonstration at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival that was so shockingly lifelike that he wondered, “If we can be anything we want here, why would we ever leave?” This first volume in a scheduled trilogy does a decent job of setting up that conundrum. Otherworld’s teenaged protagonist, Simon, is a rich kid who hates his parents, and whose most prominent characteristics appears to be a strong sense of rebellion and a really big nose, shared by his avatar. He’s still pining over his best friend, Kat, after she deserted him, when she gets caught in an explosion that leaves her in the comalike “locked-in” syndrome. She and other comatose patients then receive special disks that enable them to enter the exclusive game of Otherworld. Simon grabs his own disk try to find Kat in Otherworld and bring her back to consciousness.

Maybe we’ve all been spoiled by such well-crafted worlds like J.K. Rowling’s, Suzanne Collins’, Rick Riordan’s, and even Veronica Roth’s in her Divergent series. Otherworld is a bit harder to get a handle on, as it has to create its own universe for the game right out of the gate. The game has realms that appear to be loosely based on the seven deadly sins, like Nostrum, a murder-filled jungle that preys on the players’ unbridled rage, and the greed-fueled world of Mammon, where the inhabitants are involved in an unending accumulation of wealth and riches that will never be enough. Of course, Imra is a hedonist’s paradise, filled with drugs and food and orgies. As Simon navigates these strange lands, helped along by avatars like soccer mom Carole and ogre Gorog, he finds that Otherworld has an effect on him, more than the other way around. For example, as he stands over his first kill in Nostrum, “Hot blood pours out of his body and over my hand. It feels fantastic. Not as good as sex, but damn close.”

What’s more problematic is Otherworld’s bizarre and intersecting hierarchies of avatars and nonplayer characters versus non-NPCs; what’s artificial intelligence and what isn’t; and the “guests” who are the players of the game, and the Elementals (leaders of each realm), Beasts, and their unfortunate mutant offspring, called Children, who roam the unfamiliar terrain of Otherworld, trying to win it back from the guests. Like a first-time player, it takes a while for the reader to get a handle on it all, but that knowledge becomes fairly solid by the end of the book. More successful are Simon’s forays back into the real world, as he travels between Otherworld and reality trying to uncover the conspiracy of The Company behind the game, what its true purpose is, and why it is that for some of the players, like himself, their death in Otherworld will translate into death in the real world as well.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.