As children, we learn three things about the shark: that its skeleton is made of cartilage, like your nose; that when it loses a tooth, another will pop up in its place; and that if it stops moving, it will die. None of this information is comforting, given what we instinctively believe about the toothier members of the superorder Selachimorpha: that they are dead-eyed swimming and killing machines that prey on dipped toes, thrashing legs, and our fears about open water. Never mind that few species of shark are dangerous, or that one is much more likely to be killed by a cow than a shark. The dorsal fin is one of the animal kingdom’s masterstrokes of branding; it looks like a tooth, and we don’t need to see the rest of the shark to have the bejesus scared out of us. The classic Jaws exploited this effect (due in part to malfunctioning animatronics, which necessitated keeping the man-eating shark off-screen), and in the process taught the world that a creature feature could make Scrooge McDuck-ian piles of money. But if there’s anything that these last four decades of Jaws knock-offs and wannabes have taught us, it’s that it takes a Steven Spielberg-level talent to make a great movie about a killer shark.

The Meg, in which the bullet-headed Jason Statham faces off against a humongous prehistoric shark, owes even more to a later Spielberg hit, the Michael Crichton adaptation Jurassic Park, than it does to Jaws. In fact, Steve Alten’s crummy, sub-Crichton potboiler Meg: A Novel Of Deep Terror was first optioned in 1997, when Hollywood was in the middle of its post-Jurassic Park boom of rehashed monster B-movies. Over the years, it’s passed from director to director, changed studios, and gained a definite article along with what appears to be a significant Chinese investment. One presumes the added “the” is meant to avoid confusion, so that audiences know that the movie isn’t about a Meg or Megan that they know, but the Meg: the extinct Carcharocles megalodon, of which nothing survives except teeth and coprolites, i.e., fossilized turds. From these, science has deduced the following: that megalodon was the biggest and baddest of all sharks and, less cinematically, that it had a lower intestine not unlike that of some modern shark species. Scientists estimate its length at around 40 to 50 feet, Alten’s novel bumps it up to 65 feet, and the movie ballparks it at “75 to 90 feet.”

This ancient, ugly cartilaginous bastard with rows of snaggleteeth takes its time showing up. After a prologue that introduces the deep-sea rescue specialist Jonas Taylor (Statham), director Jon Turteltaub (better known for his fun National Treasure movies) fast-forwards some years and whisks us away to Mana One, a high-tech marine research station where Dr. Zhang (Winston Chao) is readying an expedition to prove his theory that species long presumed extinct have survived in a hidden part of the Mariana Trench. After a languorous stretch of exposition that introduces a lot of pseudoscientific mumbo-jumbo and enough supporting characters to fill a Dickens novel (played by the likes of Rainn Wilson, Cliff Curtis, and Ruby Rose), we follow a three-person submersible down to the ocean depths. There, it is attacked and disabled by a big, unseen blob. That’s when Jonas re-enters the picture. It turns out the pilot of the submersible, Lori (Jessica McNamee), is his ex-wife, and the Mana One’s medic (Robert Taylor) is the same guy who blackballed him years ago for blaming the deaths of his partners on a sea monster. Jonas has spent the last few years drinking himself into a stupor in Thailand, but apparently, one chopper ride to Mana One and some ill-defined motivation is all it takes for him to kick the bottle.

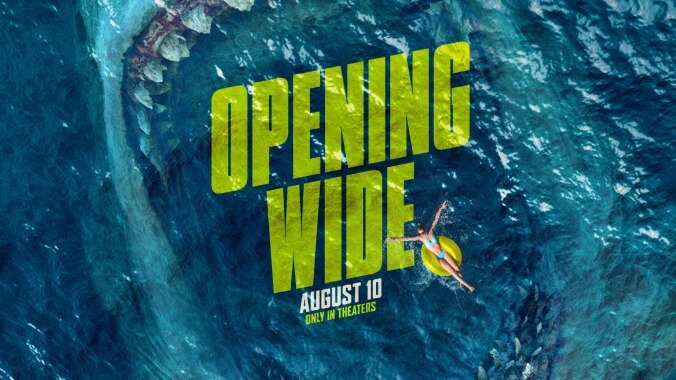

It’s never really clear what Statham, the limiest of limeys, is doing in The Meg; though it does briefly take advantage of his background as a competitive diver, the role mostly relies on his furrowed brows and less-than-sparkling chemistry with Zhao’s recently divorced daughter, Suyin (Li Bingbing). If the movie can’t get us to care about these characters and their pointless backstories, it can at least provide us with the sick thrill of watching people get eaten by a big-ass shark. (After all, it has so many cast members to expend!) But it’s only toward the end that the film acknowledges its potential for sadistic, Piranha-esque mayhem. As an escaped megalodon swims close to a busy beach, we see humanity at its most chompable: chubby kids in floaties, doofuses on pontoons, some dork in a tight Speedo rolling around in one of those big inflatable Zorb balls. But alas, the movie is a gore-free PG-13, and though CGI has long since replaced animatronics as the monster movie’s weapon of choice, one thing hasn’t changed: giant killer fish still look like they’re made of rubber.

Then again, Turteltaub’s direction never suggests that it’s motivated by anything except commercial and contractual considerations. The Meg is lackadaisically paced, dull to look at, and has trouble keeping track of space and plot (it’s never clear what Mana One does), but it’s always very clear on what kind of expensive watches the characters are wearing; at any given moment, a scene might be interrupted by a reaction shot awkwardly centered on someone’s wrist, the sleeve tucked down to showcase yet another hockey-puck-sized piece of waterproof horological luxury. Whoever negotiated the placement of those watches got their money’s worth. You won’t.