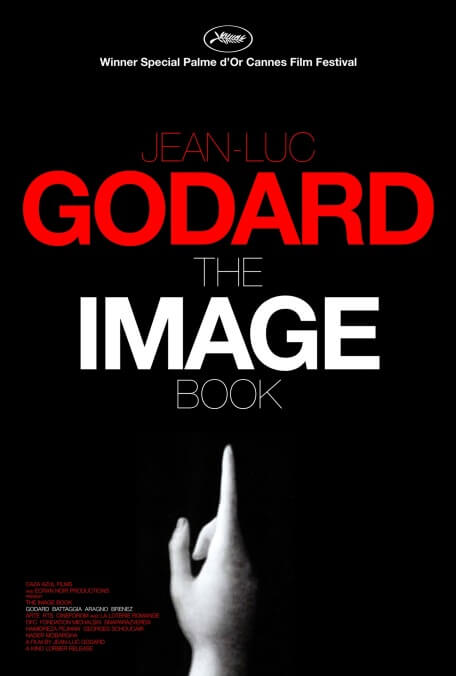

Deemed so unclassifiable by Cate Blanchett’s 2018 Cannes jury as to merit an entirely new award, the “Special Palme,” Jean-Luc Godard’s The Image Book is as dense and alienating as anything the iconoclastic director has made this century. No longer the relatively mainstream artist of the French New Wave, Godard has spent much of his time since the ’70s reinventing his style by experimenting with new technologies, cameras, and media. And yet, unlike 2013’s Goodbye To Language, his groundbreaking foray into the realm of 3D, this new patchwork largely consists of techniques, images, and aphorisms that have recurred throughout his storied career. It’s telling that while making his latest, the French-Swiss filmmaker returned to the same equipment he used two decades earlier to develop Histoire(s) Du Cinéma, a 265-minute opus assembled from 19th-century paintings, images from 20th-century catastrophes, and works from his personal cinema canon (including films by Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles)—all of which are the basis for the collage aesthetic of The Image Book. No wonder the first chapter is titled “Remakes.”

The Image Book is composed of five semi-distinct segments, each of which correspond to a finger from the hand of Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist (the film’s first image, believed to be the Renaissance painter’s final work): the aforementioned “Remakes,” contrasting war footage with films that internalize historical trauma; “St. Petersburg Evenings,” which contains the film’s most luxurious pastels, from an abstract smearing of Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard to the vibrating impressionism of severely degraded footage from Sergei Bondarchuk’s War And Peace; “Those Flowers Between The Rails, In The Confused Wind Of Travels,” a treatise on cinema’s most enduring icon, the train; and “Spirit Of Laws,” which juxtaposes scenes of Western corruption against the ideal wholly embodied by Henry Fonda in John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln. Like every other film from the director’s late period (from at least 2001’s In Praise Of Love onwards), The Image Book sets out to offend aesthetic norms. The sound is out of sync, the montage moves too fast, the aspect ratio constantly shifts, and the images strobe between varying levels of degradation. To the untrained eye, the film could appear amateurish. But its beauty lies in what seems like deficiency.

Although Godard never once appears on screen (his image figures heavily throughout Histoire(s)), his presence is made known through aural intrusions on the blaring 7.1 Dolby Atmos sound mix. Godard’s raspy, immediately identifiable voice booms from all corners of the theater, pouring out from isolated channels to one’s right or left, back or front. It can be frustrating, if not impossible, to make out the precise content of Godard’s mumbling (not in the least because, once again, only half the film has been subtitled for English-language viewers). But even when it seems as though the filmmaker is trying to summarize decades of inquiry within the span of an hour, his intonation evokes a multitude of passion, feeling, and anguish that exceeds mere thought.

Uttered in Histoire(s) and again here, Godard’s cryptic edict that “man’s true condition” is to “think with his hands” has an uncharacteristically literal significance. In describing the film’s production, co-editor, co-producer, and cinematographer Fabrice Aragno (who also worked on Goodbye To Language) stated in an interview with Film Comment that Godard edited on analog video, leaving behind “mistakes,” like the deliberate gaps between images or abrupt changes in aspect ratios; Aragno would then directly transcribe these sequences into digital editing software more in keeping with contemporary standards. There’s a pragmatic reason for this production cycle: Godard is getting old and lacks the nimbleness required for digital editing. Every frame in The Image Book thus indexes the physical hands of its maker.

The extent to which Godard emphasizes his own presence is strange in light of the formal strategies he has developed since his post-1968 films. One of the primary objectives of the Dziga Vertov Group (founded by Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin in the wake of May 1968 turmoil in France) was to dismantle the idea of the “auteur,” which Godard helped popularize during his tenure at Cahiers Du Cinéma. His subsequent films often question the ethics of authorship: how to limit the “violence of representation,” the reductive frameworks imposed on the camera’s subjects, particularly those “foreign” to the West.

This is the subject of The Image Book’s final and most ingenious chapter, “La Région Centrale” (named after Michael Snow’s 1971 avant-garde milestone). Where the previous four movements connected cinematic and real-world violence, this extended essay on “Joyful Arabia” considers cinema’s legacy as an ideological weapon. Its narrative—and indeed this is one part of the movie that can be said to tell a story—comes from a book called Une Ambition Dans Le Désert by the Egyptian-born French writer Albert Cossery. Integrated without annotations, excerpts from Cossery’s text are read over Western-produced images of the Middle East (including those from Michael Bay’s 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers Of Benghazi), nonfiction footage of the Arab Spring, and numerous indigenous films that will be unknown to most English-language viewers. Making the most of a presumed Western ignorance, this section projects fiction as history; it discusses the life of “Ben Kadem,” the leader of a Persian country unravaged by American imperialism, as if he were a real person.

If Godard weren’t Godard, would we be so inclined to accept this faux history lesson as truth? To put it another way, what does it mean that Western viewers, potentially unaware of the region’s aesthetic traditions, might even assume this passage authentic? Couldn’t Godard’s auteur status then be used to obfuscate, misrepresent, or even do harm to the region and people that, through his career, his cinema has sought to defend? Now 88 years old, his voice crackling on the soundtrack, Godard appears to question the legacy of his artistic militancy, or perhaps, even the very notion of the author. All that remains for him now is to write his own elegy. The Image Book concludes with a scene from Max Ophüls’ Le Plaisir: a man dancing around, around, and around, until finally, he collapses.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)