Is there a more pathetic object of desire than Captain John (Thomas E. Breen), the one-legged American who becomes a figure of romantic fantasy in The River? Breen was all of 26 at the time of filming, though like so many of the World War II generation, he seems a good decade older. His red hair is gelled back in sticky waves, his pants are belted mid-abdomen, and his shirts and jackets are cut baggy. His clothes drape awkwardly over his body, and at the pivotal moment of the film—the moment when Captain John’s false leg gives out from under him—they seem to drift an inch behind him, like parachutes unfurling too late.

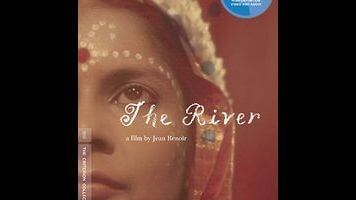

Released in 1951, The River was Jean Renoir’s first film in color, and is now widely seen as the start of the French master’s late period; plenty of filmmakers and critics have argued for it as the highpoint of Renoir’s post-war career, equivalent to The Rules Of The Game, Renoir’s pre-war consensus masterpiece. It is, in some ways, an easy movie, which is to say that it’s easy on the eyes and that it lacks the wild contrasts of acting style that defined Renoir’s 1930s work, moving instead with a dreamy effortlessness. Lacking complicated camera movements—which Renoir, shooting on location in India, didn’t have the resources to mount—or marquee stars, The River relies almost entirely on Renoir’s mastery of filmmaking basics. Yet it’s also a complex and mysterious work.

The setting is indeterminate. Rumer Godden’s semi-autobiographical novel, which she adapted in collaboration with Renoir, took place in the early 1920s, but there are no visual cues as to the exact timeframe. The India seen here—filmed with the help of a largely local crew that included future great Satyajit Ray, as well as Ray’s soon-to-be collaborators Bansi Chandragupta and Subrata Mitra—is the India of the early 1950s, but it could just as easily be (and, in fact, often seems to be) India under the British Raj. Captain John is a veteran of what is only referred to as “the war,” and contemporary reviews suggest that, to viewers in 1951, that meant the one that had ended just a few years prior. (Breen, son of head Hollywood censor Joseph Breen, was a World War II veteran, having lost a leg in the Battle Of Guam.) And yet everything about Captain John suggests the archetype of the forgotten man of the post-World War I years.

Which is to say that while most commentaries on The River have focused on its imagery of a timeless India seen from the perspective of English and American whites, its version of the West seems equally out-of-time. For all its rich sensitivity, The River pivots on an irony as biting as anything in Renoir’s canonized pre-war French work: that in a place as widely exoticized as India, a social nobody like Captain John would appear enigmatic and exotic. Foreignness, which can be as tantalizing as beauty, is similarly in the eye of the beholder. There is a pervading sense of two timeless worlds locked in mutual fascination—which is appropriate, because The River is a movie about desire, rendered in complex terms. It’s a movie about India and the West, but also about the masculine and the feminine, figurated as lonesome colonials or as characters of local myth.

There is Harriet (Patricia Walters), teenage daughter of a British jute merchant. Captain John is a cousin of her neighbor, called Mr. John. Harriet scribbles about him in her diary and writes him fancy formal invitations to dinner—the stuff of romantic make-believe. Her best friend Valerie (Adrienne Corri) openly flirts with him. They are maybe a couple of years apart at most, but Harriet’s doll-like dresses pin her as a young girl, while Valerie’s bare shoulders, brushed by long hair, create at least the illusion of free-spirited sexuality.

Captain John, who is kind of a doofus, fumbles between treating them as adults and children, as though he hasn’t been desired for a long time or maybe ever and doesn’t know how to behave himself. This is desire defined by fluctuating boundaries and vulnerabilities, complicated by age and fantasy and by Captain John’s unconcealed attraction to the half-Indian, half-English, age-appropriate Melanie (Radha), herself an object of fascination for the girls, especially Harriet. The title is usually taken to refer to the popular Western image of India as an unchanging place of constant movement, but it could just as easily refer to these needy one-way relationships, or to the way the movie accumulates details and subtleties as though they were tributaries flowing into a larger body.

Though subsequent films like French Cancan would find Renoir experimenting further with stylized color schemes, The River—painted mostly in vivid Technicolor brown and green, the colors of the countryside—makes remarkable and pointed use of isolated bursts of color. (It can’t have been an accident that all three of the movie’s major white characters, though unrelated, have red hair.) And here, in a project that relies so heavily on young and non-professional actors, Renoir’s knack for handling and editing performance becomes self-evident. Framed right, their awkwardness becomes characterization and depth. The result is a work of careful construction, with moments of graceful lyricism and subtle tragedy, which seems to move as elegantly and mysteriously as rivers do.

The River is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Criterion. It’s also currently streaming on Hulu Plus.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.