Jeff Tweedy shows a lot of himself in his memoir, just not what you’d expect

There’s a single line that’s tossed off midway through Jeff Tweedy’s new memoir that effectively sums up the entire book: “I just like writing songs.” Those five words come in a chapter in which the Wilco frontman discusses his writing process. He constructs the music first and then adds gibberish to help discern the song’s vocal melody. It’s a roundabout way of explaining that his songs rarely have an inherent meaning, as he feels the music itself expresses everything he wants and the words are an afterthought. Tweedy just likes writing songs, and there’s not much more to it than that.

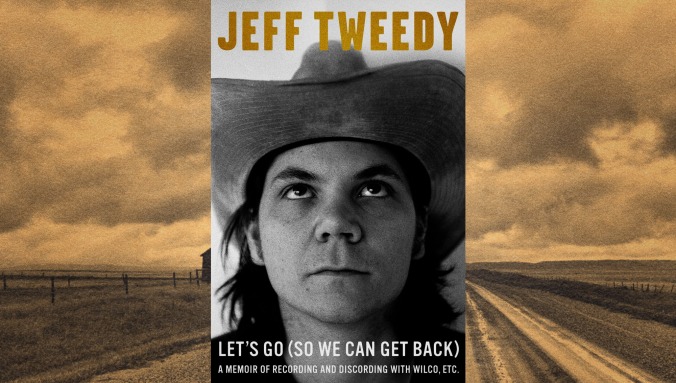

As a memoir, Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back) functions in a similar way. Much like Tweedy knows songs should have meanings, he knows a memoir should have anecdotes that speak to who he is as a person. And while Tweedy provides those, they are often minor moments, the kind that imprinted deeply on him but could seem like random recollections to anyone else.

If that sounds like Tweedy avoids writing about himself, that’s not entirely accurate, but he does take a slightly sideways approach. The stories from his childhood are largely about music, be it hearing bands like the Ramones and The Clash, or traveling to a dingy club to see The Replacements. While details of his early life are present and accounted for, Tweedy’s writing is at its most evocative when he’s explaining how the songs he loved changed his worldview and pushed him to become a musician.

There are even moments when he effectively cedes control to his family members, presenting conversations with them about what should be included in the book. And while that sounds like an unnecessary deviation, it actually lends a great deal of insight into Tweedy himself. These passages are illuminating because Tweedy avoids rehashing the most sensational moments of his life and instead explores what was happening inside his head and how it was affecting the people closest to him, who aren’t shy about sharing their honest experiences either.

Unlike a biographer, who might attempt to prop up Tweedy’s achievements and legacy, he often finds himself pushing back against those things. The self-deprecating memoirist is in itself a cliché, but it’s telling just how authentic Let’s Go feels when taken as a whole. Instead of feeding the lore behind the dissolution of Uncle Tupelo, or rehashing the drama surrounding Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, he writes about those situations as if he were still unpacking them himself. He does get into why his relationships with Jay Farrar and Jay Bennett ultimately dissolved, but he approaches each situation with relative grace. Tweedy explains his side of things while still showing a genuine affection for the collaborators with whom he had very public fallings-out.

Tweedy saves the barbs for himself, taking digs at his singing voice and offering a warts-and-all depiction of his struggle with addiction. Often times, Tweedy’s presents his past self as a character unworthy of sympathy, which makes the book’s end, where he finds peace in spite of that, that much more compelling. As a result, it’s easy to get the sense that his guard is down throughout Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back). The stories he elects to tell may be frustrating for fans who want to learn more about, say, the creation of specific Wilco albums, but it offers a compelling portrait of an artist whose everyman nature proves to be anything but a front.