Landline is set in 1995. The movie announces as much from the start, but it doesn’t really need to, because scarcely a scene passes without some reminder of this fact. There are, as one might expect, several landline telephones. A younger Hillary Clinton shows up on television, sadly unaware of what the audience knows about her future. Characters discuss Mad About You, rent movies at Blockbuster Video, and crack jokes about Lorena Bobbitt. At one point, someone puts on P.J. Harvey. At another, someone listens to a CD at one of those record-store headphone stations. Not every detail is 100-percent accurate: A scene at an arthouse movie theater, for example, includes a poster for Chungking Express, but the artwork is from the mid-2000s Criterion release. Yes, that’s a nitpick, but any movie this obsessed with its near-past setting should at least get the period signifiers right.

There’s no particular reason why this movie had to be set in 1995. The Big Sick, which coincidentally premiered right after it in the same theater at Sundance this year, smartly opted to relocate its true story to present day, mostly to avoid the very kind of distracting signposts of era that Landline actively embraces. The film is set when it’s set because its director, Gillian Robespierre, and one of her cowriters, Elisabeth Holm, grew up in New York City during the mid-’90s. Like the pair’s last collaboration, Obvious Child, this new one is a minor, slightly tidy, but very likable indie showcase for Jenny Slate. Unlike Obvious Child, it’s more of an ensemble piece, planting the comedian at the center of several intersecting storylines. Landline doesn’t need its bevy of nostalgic cultural references (the story would work just fine in the here and now), but it’s not like these I Love The ’90s callbacks really spoil its pleasures, either.

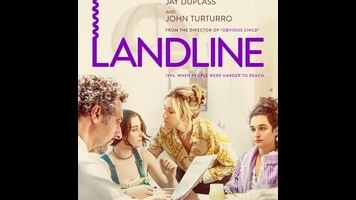

Building another screwball neurotic around her loopy comic charm, Slate plays Dana, eldest daughter of a Manhattan family in crisis. Dana is engaged to be married to Ben (Jay Duplass), but she’s restless, and her cold feet send her running into temptation—specifically a flirtation with an old college hookup (Finn Wittrock). Perhaps infidelity runs in the family: Dana’s father, failed playwright Alan (John Turturro), has at the very least been “emotionally cheating” on her mother, overtaxed EPA agent Pat (Edie Falco). Dana learns this because her rebellious teenage sister, Ali (newcomer Abby Quinn), discovers their father’s secret stash of love poems, addressed to someone named “C.” In so much as Landline has a plot, as opposed to a series of shaggy character moments, it concerns Dana temporarily moving back into the family home, helping her sister snoop on their dad to avoid confronting her own pre-wedding jitters and transgressions.

Robespierre and Holm create a credibly complicated New York clan, speaking with candor in the moment (they’re the type of family that fancies themselves able to talk about anything) but often hiding their true feelings from each other and themselves. Landline has an occasionally ribald comic snap, too, scoring laughs from sexual misadventures. (A golden showers joke, for example, distinguishes Robespierre’s voice—if this is her version of a genteel Nicole Holofcener family comedy, it’s at least a more winningly profane one.) But it’s the cast that sells the relationships. Turturro and Falco conjure the impression of a domestic comfort dimmed by unspoken tension, while Quinn impressively throws up a wall of withering teenage resentment, while offering periodic peaks to the vulnerabilities on the other side. (She also as a beautiful singing voice—something in the neighborhood of Regina Spektor, to make a non-1995 allusion.) It’s Slate, though, who offers the most indelible character—a woman taken aback by her own desires and desperation. As in Obvious Child, she makes “flailing,” in Dana’s own words, touchingly funny.

Landline rarely feels less than truthful, but there’s also something a little sitcom-easy about its storytelling. This is the kind of movie that acknowledges that there are no quick fixes for a life’s (or a relationship’s) big problems, while still resolving the messes its characters make too cleanly. Still, Robespierre remains great with her actors, with the crackle of their warmly adversarial rapport, and especially with the little stuff: the way Ali says “love you” back to her mother after she’s left the room, or how Dana nonchalantly plows through her phone messages, blithely slipping past one about a desired wedding venue in a way that speaks volumes about where she’s at emotionally. It’s the kind of revealing detail that matters. That she checks those messages on a payphone doesn’t so much.

Correction: This review originally stated that Jenny Slate grew up in New York City. She was actually born and raised in Milton, Massachusetts.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)