Jenny Slate’s memoir is as strange and whimsical as she is

Readers have come to expect certain things from a comedy memoir, especially when it’s written by a woman. There are amusing descriptions of their awkward adolescence, followed by the wry exploration of their years spent trying to make it in an industry littered with crass men, hyper-competitiveness, and the impossible standards set by Hollywood. Finally, a breakthrough and the candid bewilderment of being the weird, loud, adjective-not-usually-considered-feminine center of everyone’s attention. It’s not a bad formula, and for a profession that relies on voice as much as comedy does, it works. Still, there tend to be few surprises when it comes to more literary matters like, say, structure or less conventional genres.

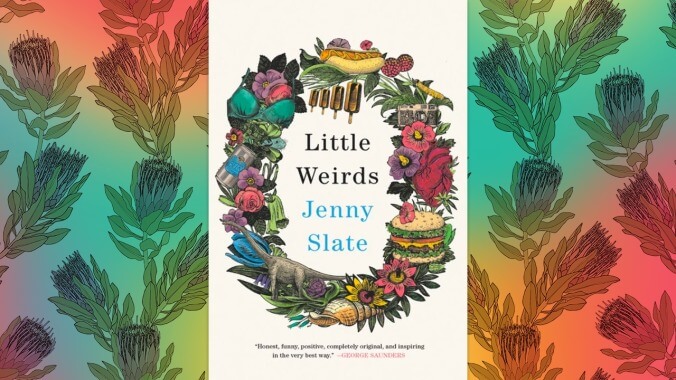

Every so often, someone will decide to stray from that outline and gift us with something so unexpected that it may not tickle our funny bone but it might tickle us pink. Jenny Slate’s nonfiction collection Little Weirds is one such book. It’s an extremely personal narrative, and there are elements of humor in it, but that may be all it has in common with the efforts of her peers. Slate—who in some circles is best known for playing the Id-driven Mona Lisa on Parks & Recreation; voicing Marcel The Shell and a series of other cartoon characters in others; and as Captain America’s ex in yet other circles—has made a career for herself by voraciously embracing and thriving in the niche, to the point where everyone seems to recognize her even if they can’t quite place exactly from where. In this way, the oddness of this genre-defying book fits in nicely with the path she has set out for herself as a performer.

The book is mostly composed of vignettes detailing scenes, moments, and thoughts from Slate’s life. There are flash essays peppered throughout, consisting of a paragraph at most. The aesthetic is more small press chapbook of lyrical prose than personal essay. One will find descriptions of a conversation with her mom about flowers, her creepy description of her haunted childhood home, an absurdist breakdown of an everyday activity like going to a restaurant, and speculations on what dreaming about a massive dog who is also a spirit guide might mean. What readers won’t get are straightforward chronological facts about Slate’s rise to fame nor any insider gossip about the inner workings of Hollywood. “This book is the act of pressing onward through an inner world that was dark and dismantled,” she explains early on. A collection that relies so heavily on whimsy shouldn’t be this effective, but the emotions in it are so raw that delving into her words creates an intimate connection to the work.

What does permeate these pages is a lot of heartbreak. The book is at its most poignant when she focuses on the loss of love. There is no need to know the details of her divorce from filmmaker Dean Fleischer-Camp or her subsequent romances to feel moved by the sadness that followed or her earnest hunger for a partner. There is an undeniable feminist bent to the book, like an entire chapter on how the Code Of Hammurabi basically ruined the relationship between the sexes, which prevents her desire from coming off as doe-eyed. In fact, it’s refreshing to have someone lay bare the gamut of emotions that come with a breakup beyond anger, though that is included as well. “I Died: Listening” may have one of the more relatable descriptions of gaslighting to date: “It is hard to even describe what it’s like to have someone use your own revelation of suffering as a way to accuse you of being cruel.”

Even so, it’s the tender imagining of growing old with someone or the vulnerability of a trip to the Arctic Circle, where she quietly crushes on a tall, handsome man, that stand out for their honest longing. On this vacation, we hear about a plate of sausages that give her joy, how much she loves her friend when she realizes she forgot to bring wine, and seeing her crush’s butt when he skinny-dips. (Slate is a comedian, after all, and there is still some levity.) It’s the power and the beauty of tiny moments like these that Slate is interested in mining. As she concludes at the end of her vacation, “Something had happened but nothing had happened, really. Nobody touched me but it felt like I had been touched.”

Because of her preference for these small experiences that still pack an emotional punch, it’s hard to determine who the audience is for this book. With a new Netflix special under her belt, there may be more hardcore Jenny Slate fans than expected, ready to follow wherever her fascinating-but-strange mind may lead. This isn’t, however, a collection that aims for wide appeal, and therein lies both its strength and its weakness. If it weren’t for Slate’s truly admirable writing chops, made more exuberant with her knack for fanciful descriptors, it could easily run the risk of coming off as precious.

There is the very real possibility that Slate cared little about catering to the common denominator when writing Little Weirds. “This book is me putting myself back together so that I can dwell happily in our shared outer world,” she writes, and she takes us through the internal journey of picking up the shattered pieces of her previous life to rebuild a new one. It is a strange read, an odd look into personal pain, but an engrossing one—what we get are no little insights but a big chunk of heart.