When Quentin Tarantino coined the term “hangout movie,” he was describing one of the greatest Westerns ever made: Rio Bravo, Howard Hawks’ 1959 masterpiece, which kills most of its running time just laying low with a small-town sheriff and the motley posse he’s assembled to guard a jailhouse, eavesdropping on their conversations as they dig in their spurs and chew the cud. The film, talky and at times nearly plotless, brought the Wild West to life in a different way: These weren’t just mythic archetypes we were watching but complicated people, with personalities and hang-ups and whole interior lives. The Sisters Brothers, a new Western directed by Jacques Audiard (A Prophet, Dheepan) and adapted from the acclaimed novel by Patrick DeWitt, spans a larger geographic radius than Rio Bravo—it’s a kind of road picture, ambling across two states, instead of plunking us down in (basically) a single locale. Nevertheless, there’s a strong whiff of Hawks’ classic in the movie’s conception of its titular outlaws as neurotic chatterboxes. It’s something of a hangout Western, too, and its pleasures mostly come down to the company we get to keep with the characters and the actors easing into their eccentricities.

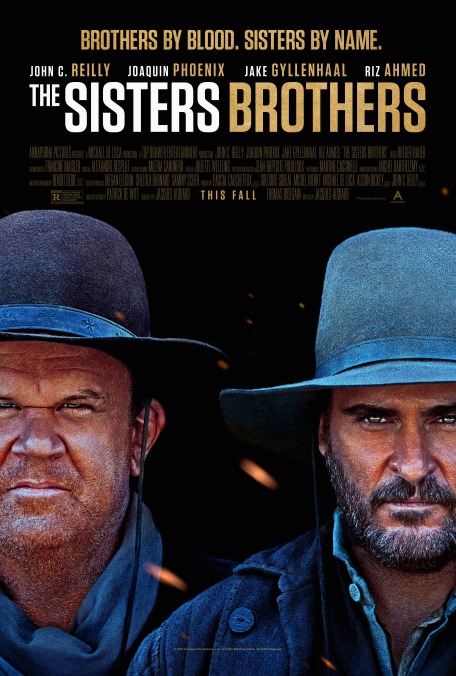

The Sisters brothers are Eli (John C. Reilly) and Charlie (Joaquin Phoenix), squabbling guns for hire. They drop bodies and chase bounties for a mysterious (and largely unseen) Oregon City baron called simply The Commodore. The work suits Charlie, a drunk and maybe a sociopath, who enjoys trouble. But Eli has grown weary of the outlaw life, of killing to make ends meet. Reilly, in a rare starring role, foregrounds the sadsack melancholy that seems to gather around the edges of even his broadest comic performances. He plays Eli as a soft soul born into the wrong family, the wrong line of work, maybe the wrong era altogether—a decent man worn down by the moral toll gunslinging takes. He’s a fine foil, too, for Phoenix, who makes Charlie a figure of casual destructiveness, his menace somehow amplified by his pratfalls. The two forge a bond of believable brotherhood: competitive and petulant, driven by hurt feelings, a shared sense of humor, and a love never entirely obscured by antagonism.

We meet the Sisters boys, and become familiar with their contentious rapport, in the opening minutes, when they get the drop on some marks at a farmhouse, their gunfire cutting through the total black of night with brilliant flashes of illumination. (Benoît Debie, who shoots all of Gaspar Noé’s work, provides some striking images, even as he sticks to an earthy, decidedly non-mythic style that aligns well with the movie’s ramshackle spirit.) There’s more violence to come, but it’s not really the meat of The Sisters Brothers, which is more interested in shooting the breeze than shooting rifles. The episodic structure—an incident involving a poisonous spider; a pitstop in a town named after its wealthiest resident—is straight from DeWitt’s bestseller, which let the sibling rivalry move things along, from one misadventure (and punchy, plainly written chapter) to the next.

Eli and Charlie end up picking up a job that sends them from Oregon to California. Their target: the prospector Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed), who’s invented a chemical formula for revealing gold in riverbanks—a fine metaphor for the hidden good the movie sometimes finds in bad men. The Commodore has sent ahead a scout, the dandy John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal, with a hilariously proper accent), to keep an eye on Hermann before his killers arrive. This Nightcrawler reunion provides The Sisters Brothers with a complimentary mismatched buddy movie, running in parallel to the one Eli and Charlie are bumbling through en route. The tone veers comic (it’s not so hard to imagine Reilly, ever the generous scene partner, paired off with Will Ferrell in a dopier version of this material), but the film never sticks the Western in quotation marks, never condescends to the genre with a wink.

It might seem, from a distance, like a change of pace for Jacques Audiard, making his English-language debut. But the French director often specializes in finding hints of sensitivity in prototypically macho figures: Think of the fighter-who’s-really-a-lover that Matthias Schoenaerts movingly portrayed in Rust And Bone, or the tenderness exhibited by the title character of the inexplicably Cannes-winning Dheepan, at least before he goes full Travis Bickle. Like plenty of Westerns before it, The Sisters Brothers can feel like a eulogy for its own legendary time frame; everything from an early toothbrush to a bustling San Francisco portend an encroaching modernity. But that rapid change—so often greeted with ambivalence if not outright distrust by the genre—could also bring emotional enlightenment, embodied by Ahmed’s good-hearted dreamer, whose idealism proves catching. The best moments of this rambling, minor-key frontier story, like a hilarious and touching encounter between Eli and a prostitute (Fargo’s Allison Tolman), are the ones that find vulnerability in rakes and rogues, pulled away from their baser instincts by their consciences, and by the bonds of friendship and family. There’s something a little Rio Bravo about that, too, isn’t there?

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)