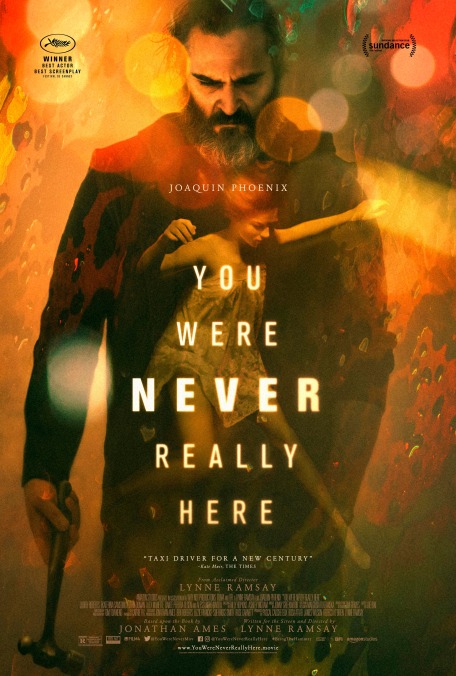

Joaquin Phoenix is a human wrecking ball in Lynne Ramsay's electrifying You Were Never Really Here

In Lynne Ramsay’s fragmentary, ferociously beautiful You Were Never Really Here, the great shape-shifter Joaquin Phoenix balloons his body into a fearsome new form: a bulkiness every bit as convincing and psychologically revealing as the bony odd angles of The Master’s Freddie Quell. “Intimidating” isn’t a word one often uses to describe this American chameleon, who hasn’t added too many tough guys to his eclectic repertoire. But to play Joe, a mercenary with a jumbled montage of horror stories where his mind should be, Phoenix has packed on mounds upon mounds of new flesh, scribbled with battle scars that imply a whole history of violence, plus a shaggy gray beard that seems to enhance his menace and his outsider vulnerability all at once. He just looks giant, and Phoenix carries that extra weight like a weapon of mass destruction. His actual weapon, meanwhile, is a goddamn hammer.

Joe is big, but he’s also fast, moving with a scary, lumbering grace. For the right price, you can point this human wrecking ball in the direction of those you want hurt. “They said you’re brutal,” murmurs a potential client, awe and a little fear on his breath. “I can be,” Joe calmly replies. As hired muscle, he specializes in finding missing girls. Is there a personal stake, a nursed grudge, in that particular line of work? Joe, who lives with his elderly, ailing mother in New York, spends every waking moment drowning in an ocean of bad memories—the trauma bubbling to the surface of his subconscious, through unexplained and sometimes near-subliminal flashes of flashback. Some of these jarring peeks into the past imply a childhood of unspeakable suffering. Others offer a glimpse into his occupational hazards, the heinous things he’s seen and can never un-see. Still one more reveals time overseas, killing for country.

The plot, a grim little corker about a teenage girl forced into a sex ring and the bull of an enforcer who comes to break her loose, has been adapted from a novella by Bored To Death creator Jonathan Ames. Ramsay, the gifted Scottish filmmaker behind Morvern Callar and We Need To Talk About Kevin, twists the source material into a spooky haiku of carnage, short and sour. Her film unfolds in a subjective haze, through whispers and glances. Ramsay often shoots in extreme close-up, narrowing our field of vision to whatever’s caught in the crosshairs of Joe’s thousand-yard stare, and she captures his raw-nerve sensitivity by turning the normal sounds of the city into a deafening symphony of noise—PTSD as a sonic assault. We’re locked into the embattled headspace of this broken, suicidal man, barely keeping his grasp on his own sanity, let alone the specifics of his case. Admirably resistant to explaining itself, You Were Never Really Here counts on the audience to make connections with his submerged backstory, to sketch out its details in our own heads.

Watching Joe prowl the streets, absorbing its seediness through a car windshield, it’s hard not to think of Travis Bickle, another ex-military man determined to rescue a barely teenage girl from the clutches of New York pimps. Ramsay doesn’t interrogate vigilante “justice” the way Scorsese did; if this is a modern Taxi Driver, shattering that classic into shards, it’s one that comes closer to making Bickle look like the hero he thinks he is, albeit a seriously, perhaps irreparably fucked-up hero. The film’s genre DNA runs deeper than any one source, though. Ramsay is riffing on a whole history of lean, mean, existential crime pictures: a little of the Lee Marvin man-on-a-mission art thriller Point Blank, a little of the nocturnal seductiveness of Drive, even a touch of Steven Soderbergh’s peerlessly cool L.A. revenge yarn The Limey. And if Phoenix playing a half-mad veteran isn’t enough to suggest The Master configured into something more savage, there’s the sinister, serpentine swell of a Jonny Greenwood score. Here, the Radiohead axman uses a warble of atonal guitar, a throb of Cliff Martinez-style ambience, and that familiar, eerie tangle of strings to chart the jagged ups and downs of an unstable mind.

For all the influences glowing dimly under its skin, You Were Never Really Here remains its own bewildering animal, unmistakably Ramsay’s. The filmmaker elides a lot: exposition, finer details of the criminal conspiracy, a full sense of resolution. But she also delivers on the promise of her genre, finding electrifying, radically unconventional vantages in which to view the mayhem. One amazing sequence traces Joe’s rampage across a hotel brothel entirely from the perspective of security cameras, the big lug passing from one static angle to another, appearing for a second to deliver some righteous fury before the system cuts away to an empty frame. Ramsay also undercuts the brutality with stray, unexpected moments of tenderness. Joe, for all his merciless force, is really a deeply wounded soul. In one of the film’s strangest, most affecting scenes, a grisly showdown ends on an odd note of sing-along communion, an unlikely glimmer of compassion in the ruthless world Ramsay creates.

It’s a true tour-de-force of execution (and executions): a haunting, sometimes terrifying distortion of noir themes, refracted through the cracked prism of Ramsay’s remarkable style. But is there more to these hypnotic, disturbing 90 minutes than an exercise in giving pulp clichés the glean of art? Though no one of this writer-director’s movies is a dead ringer for another, they all seem to go deep into damaged psyches, reshaping the world around their characters’ duress. In its thin, primal skeleton of a story—and in Phoenix’s monstrous transformation at its center—You Were Never Really Here recognizes a horrible cycle: a tortured man both hounded and fueled by the traumas of his past, protecting someone who may already be too far down the same dark path he’s forged. There’s an awful thrill to walking it with them.