John Hawkes can’t jazz up the jazzman biopic Low Down

Perhaps the best thing that can be said about Jeff Preiss’ Low Down is that it opens by committing one of the cardinal sins of cinema, and then gets away with it scot-free. Beginning a film with a voice-over that isn’t used again (or only resurfaces much later) has become a mercilessly reliable indicator of shoddy storytelling, almost as transparent an admission of failure as when a film introduces voice-over during its final scene in order to wrap things up. (See: An Education.) And yet, by using its voice-over to frame the film with a lyricism that’s pointedly absent from the story it tells, Low Down crystallizes the bittersweet divide between the idyll of adolescence and the grim reality of living through it. “I often thought my father was born of music, some wayward melody that took the form of a man,” Low Down begins, the disembodied voice of a young girl telling us about the parent she loved out of proportion.

It’s hard to quantify Joe Albany’s success, beyond to say that he’s the kind of guy who has a Wikipedia page, but it’s short and below a banner that insists on verification. He was one of the few white pianists to play jazz with the great Charlie Parker (though the film insists that Parker wasn’t entirely satisfied with their collaboration). Albany spent most of his adult life defined less by his love for music than his need for heroin, caught in the infinite limbo between potential and greatness. Low Down quietly observes that agonizing morass through the widening eyes of Albany’s young daughter, Amy (Elle Fanning), who would grow up to write the memoir upon which this film is based.

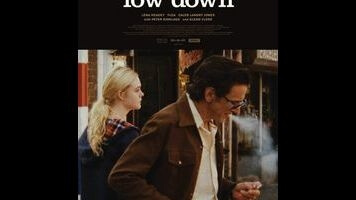

A frustrating film about a frustrated time, Low Down immediately cements the dynamic between Amy and Joe (John Hawkes). He crosses the street on his way toward her, and she watches from the window of the rundown Los Angeles apartment they share. It’s clear that she sees Joe as a lovable scamp, even before a group of men materialize and violently shake him down for some unpaid debts. He’s a man with a good heart and a bad habit, and the film about him radiates with the same conflicted sweetness.

While Joe has various places to disappear (gigs, halfway houses, foreign countries), Amy is more or less stranded at home. A teenager on the cusp of caring about the world beyond her door, she’s still young enough to be charmed by the bohemian decrepitude of her living situation. She remembers how the building would enjoy sudden yawns of breezy jazz that would carry from her dad’s living room all the way down to the lobby, and no one would complain. She also remembers the various guests that her dad would receive—parole officers on some days, junkies on others—and from whom he’d try to protect her. The most difficult times would be when her absent mother (Lena Headey) crashed into town, a tidal wave that was invariably followed by an extended visit from Amy’s grandmother (a severe Glenn Close). There were also men: a little person (Peter Dinklage) who lived in the building’s basement, and Cole (Caleb Landry Jones), the local kid who would be her first love.

Amy’s story is strung between the scorched haze of its history and the presentness of its telling. The directorial debut of cinematographer Preiss, whose career has been firmly located at the intersection between music and movies (he lensed Bruce Weber’s 1988 Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost), Low Down was shot on 16mm, and its pallid conception of ’70s L.A. provides the film with a fine texture that almost compensates for the flatness of its telling. It’s a rich, albeit limited, cinematic world, one that looks the part but never truly plays it. Fanning shines during the few opportunities when Amy is allowed to express herself, but the character is defined by a kind of passivity unique to memoirs, where life has already happened and the protagonist is overcome with powerlessness to change it. Hawkes is perfectly cast, the deep lines in his face like the grooves in one of the records Joe spins when he’s too tired to play.

And yet, the most palpable takeaway from the relationship between father and daughter is the distance between them, which is both immediately sad and enduringly dull. Shambling along with the clipped pace of a pre-war dirge, Low Down makes it as difficult for viewers to feel the virtuosic razzmatazz of bebop music as it was for young Amy Albany. It’s clear that Joe loves his daughter, just as it’s clear that his addiction doesn’t care. Low Down keeps the histrionics to a minimum, but the inertia of a good man failing to be a good father isn’t enough to sustain nearly two hours of reflection, especially when Preiss consistently suggests that telling Amy’s story from Joe’s perspective would have made for a much better film.