John Hodgman asks, “How did I get here?” in the comic and somber Medallion Status

There was a point, not all that long ago, when nearly every person in America knew John Hodgman’s face. Whether or not you were a fan of extremely nerdy books of comical fake trivia, Hodgman was briefly ubiquitous in your life, thanks to starring alongside Justin Long in a massively successful Apple ad campaign that turned his particular arch take on stolid nerdiness into an irresistible virtue. But commercial celebrity is an even more disposable commodity than most, and so while he’s worked with some regularity in film and TV since, Hodgman has mostly settled back over the years into the less rarefied worlds of literary, podcast, and comedy fame. The upshot of all this is that John Hodgman is a famous person who is not, objectively, terribly famous.

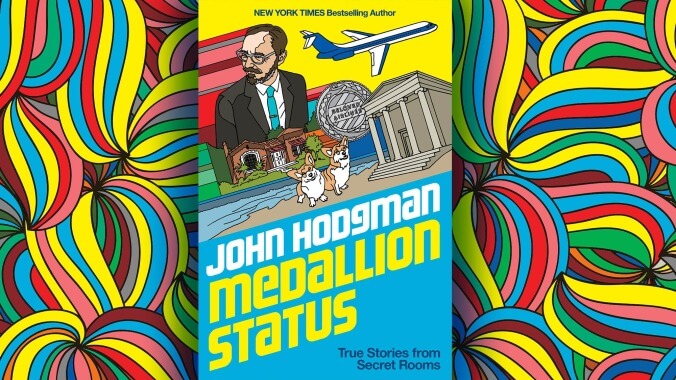

That paradox is a feature, not a bug, of Hodgman’s latest, a similarly detached follow-up to his 2017 semi-somber memoir Vacationland. Simultaneously intimate and at a remove—the tone that used to coldly dismiss readers in the form of fake trivia footnotes is still occasionally present, just more personable in its mostly mock disdain—Hodgman has moved from early autobiography and home ownership to tales of his own wildly improbable career. Knowledge of the details of that transition—from author, to Daily Show guest, to Daily Show correspondent, to inescapable Apple pitchman, and beyond—is mostly assumed at this point; instead, the focus is on the bizarre state of being liminally famous in a culture that so desperately celebrates fame. Hence the book’s central metaphor (and title): Hodgman’s acting-fueled quest to achieve a variety of precious-metal-named preferred statuses with his airline of choice, a pursuit that is as ridiculous, utterly transactional, and compulsive as the hunt for celebrity itself. (It also allows him to tell some very funny stories about the highly specific culture of airline courtesy lounges.)

Hodgman has dozens of funny stories to tell, ranging from recollections of early jobs to the time Benedict Cumberbatch messed with his mind. (Also: A lot of material on the logos of extinct hockey teams.) And yet, Medallion Status is far less gabby or tell-all than its subtitle, True Stories From Secret Rooms, might suggest. It’s telling that the question Hodgman returns to, time and time again, is not “What did Neil Armstrong or Colin Powell say next?” It’s “Why the hell is John Hodgman in a room with them in the first place?”

A book-length meditation on the old Groucho line about not wanting to be a member of any club that would have him for a member—and the sheepish admission that, actually, most of us probably might—Medallion Status can occasionally lose itself in the weeds of naval gazing, even as Hodgman’s attitude toward name-dropping sometimes threatens to breach the walls of coy and spill over into outright twee. Every once in a while, one feels urged to yell at one of his euphemistic references, “Just call it the Chateau Marmont!” And yet even as Hodgman waxes eloquently on the trials and travails of being a supporting player on the canceled FX series Married, Medallion Status stays grounded by never blinking when examining the self-loathing inherent to its titular pursuit. “This is all ridiculous,” Hodgman acknowledges with every dry aside or cheerfully dark reminder of the kids he’s flown away from for yet another TV job. And while it’s not as overtly silly a topic as the itemized lists of hundreds of hobo or mole man names that used to be his stock in trade, it’s worth remembering that taking the ridiculous seriously has always been a major part of John Hodgman’s brand.

Subtle in its wider concerns—to the point that it sometimes resembles little more than a series of vaguely related anecdotes, including the question of whether Hodgman ever did, or did not, shit in Paul F. Tompkins’ bed—Medallion Status relies on an underlying sense of melancholy to unify itself around its chosen themes. There are jokes and humorous asides aplenty, but to the extent that the book is a comedy, it’s one of unalterable human folly. Whether partying with the awkward youths of a Yale secret society or road-tripping to stand outside the equally dismal Mar-a-Lago or the Florida headquarters of the Church of Scientology, Hodgman exudes a relatable sense of exhaustion, not just at the world, but at his own desire for more than what he’s already got.

Medallion Status is by no means a depressive or dour slog—Hodgman relates these stories, about Paul Rudd, about Disneyland, and, yes, also, about airlines, to his readers in a style that is conversational, funny, and still filled with clever little switchbacks and verbal tricks. But the underlying sense never stops being of a man who has accepted that part of him will always be an outsider, no matter how many secret rooms he’s invited into.