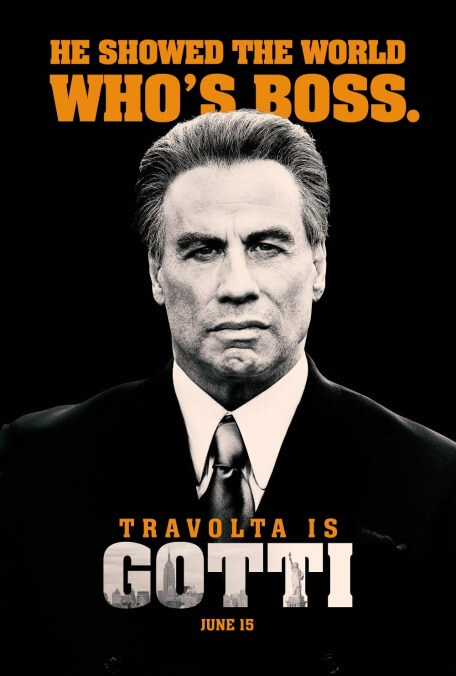

John Travolta and E from Entourage turn infamous mob boss Gotti into a scowling bore

Mob boss John Gotti—dubbed the “Teflon Don” after repeatedly being acquitted of crimes that he’d obviously committed—often sported a knowing smirk in public, taking evident pleasure in having literally gotten away with murder. Precious little of that mocking arrogance turns up in Gotti, a weirdly fawning biopic directed by former Entourage star Kevin Connolly. Working from clichés derived from other movies, John Travolta scowls and barks his way through the title role, rarely coming across as more than a generic (if unusually well-dressed) New York wiseguy; when Gotti tells viewers, speaking directly to the camera at film’s end, that they’ll never see another man like him, an attorney should really spring up and object that the statement assumes facts not in evidence. Indeed, by that point, it’s no longer entirely clear that Gotti is even about the John Gotti, given how much time and energy the film devotes to arguing for the comparative innocence and unjust persecution of John A. “Junior” Gotti (played by Spencer Lofranco).

To that end, screenwriters Leo Rossi and Lem Dobbs structure the film around a prison visit that Junior pays to his father, late in Gotti Sr.’s life, when he was dying from throat cancer. (Travolta goes without a wig in these scenes—a rare and refreshing sight.) As Junior pleads for Dad’s blessing to cut a deal with feds and get out of the business once and for all, Gotti flashes back to the ’70s and ’80s, following the Dapper Don’s ascent to head of the Gambino family—a position he famously acquired by having its previous occupant, Paul Castellano, gunned down in front of a midtown steak house. Connolly handles this sequence reasonably well, but it’s the only jolt of energy in an otherwise torpid movie. Gotti avoided prison for years by buying and threatening witnesses, but these machinations barely get mentioned, much less dramatized. Likewise, a neighbor who accidentally kills Gotti’s 12-year-old son, Frank, mysteriously disappears, never to be seen again, but this information is conveyed solely via a brief news report. Even Sammy “The Bull” Gravano (William DeMeo)—arguably the most famous rat in Mafia history, whose testimony finally put Gotti away in 1992—barely registers on screen before (or when!) he takes the stand.

Here and there, Connolly throws in archival footage from the period, presumably to add some New York flavor to a film that was shot almost entirely in Cincinnati. Some of these clips seem ill-advised—for example, showing the real Junior in 2009, when he was 45, then cutting directly to the 25-year-old Lofranco (with no significant age makeup), playing Junior at ostensibly the same time in his life. Footage of ordinary, presumably non-Mafia-affiliated New Yorkers protesting Gotti’s conviction and proclaiming him a hero, however, is apropos, since that’s essentially the movie’s own attitude. Gotti doesn’t pretend that Gotti Sr. was framed—he’s shown murdering people early in his “career”—but it does mostly ignore criminal acts in favor of tedious domestic melodrama (Travolta’s real-life wife, Kelly Preston, screams up a how-dare-you? storm as Victoria Gotti) and the mob equivalent of banal staff meetings (featuring Stacy Keach as Gotti’s mentor, Neil Dellacroce, and Pruitt Taylor Vince as his best friend, Angelo Ruggiero).

Martin Scorsese, too, has often been accused of glorifying repugnant characters, in everything from Taxi Driver to The Wolf Of Wall Street. That’s a blinkered viewpoint, in his case, but at least the charge has some juice. Scorsese goes to the trouble of making his antiheroes charismatic and exciting. Gotti, by contrast, inadvertently argues that John Gotti and his namesake son are too dull to be evil. It’s DrabFellas.