Movies have a long, storied history of self-fascination, and one can’t help but wonder whether part of it has to do with the fact that film sets look interesting—funny, cinematic, equipped with their own frames within frames where the difference between what’s real and what isn’t is hard to suss out. Film begs to lampoon or fetishize itself: the phoniness of props and effects, the background activity of a crew, the graceful glide of a camera dolly. Even Nanni Moretti’s Mia Madre—a minor effort in which the movie-within-the-movie never seems like a real project—can’t help but be riveted by the fake production it’s mounted within itself.

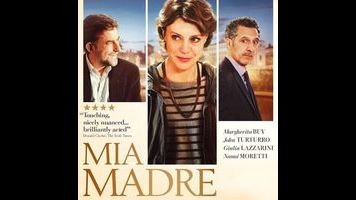

It’s a shame that Moretti can’t sustain the same level of interest in the family drama that makes up half of his latest film. With an offbeat back-and-forth structure that recalls the Italian writer-director-actor’s last movie, We Have A Pope, Mia Madre alternates between the set of a ham-fisted, sub-Elio Petri social-issue flick and the hospital where the director, Margherita (Margherita Buy), makes nightly visits to her dying mother, Ada (Giulia Lazzarini), a former classics teacher. The premise echoes some earlier Moretti films (namely, the more overtly satirical The Caiman), and as with almost all of his work, its basis is autobiographical, inspired by his mother’s death during the production of We Have A Pope. But the most personal parts of Mia Madre are also the most thinly conceived.

In contrast, the side of the film that deals with Margherita’s movie is indulgent, dominated by the persona of American ham actor Barry Huggins (John Turturro, very good), who struggles to pronounce his Italian dialogue when he can actually remember it, and by Moretti’s interest in the ricketiness of a tightly budgeted film set. One farcical sequence finds Margherita trying to direct Barry through a driving scene, only to discover that he can’t act and steer at the same time; elsewhere, the machinery of the working factory that serves as the main filming location dwarfs the meager lights and furnishings brought in for Margherita’s earnest (and seemingly awful) labor-rights drama.

The repeated use of Philip Glass’ sawing “String Quartet No. 2” to score the filming scenes is partly mocking and partly sincere; Mia Madre is mesmerized by the filming process, even at its silliest. But the two sides of the film—the wacky behind-the-scenes comedy and the family drama, linked only by the character of Margherita—don’t work together at all. It smacks of the concerns of middle-aged navel-gazing (creativity, health, therapy, political and artistic ideals, etc.), which has been Moretti’s stock-in-trade since before he even entered middle age.

His best films—like the comic quasi-mockumentary Caro Diario or the Palme D’Or-winning The Son’s Room, his first foray into drama—have put these to pointed and lucid use, but here they’re left out in the open, undigested. It’s not so much restrained as simply unwilling to budge: The relationship between mother and daughter is thinly sketched, and Margherita is less a character than a collection of relationships (to her boyfriend, to her teen daughter, to her film) undermined by an anxiety that Mia Madre never figures out how to phrase. (The lean on musical cues, including songs by Jarvis Cocker and Leonard Cohen and an embarrassment of Arvo Pärt compositions, doesn’t help things.)

The result is that Barry—the buffoonish foil of the film set, equally endearing and annoying—ends up coming across as a more complex and conflicted personality than Margherita, the gender-swapped writer-director stand-in who’s in every scene. Maybe it’s because the droll, bearded Moretti—who plays a smaller role here as Margherita’s brother, Giovanni—is the best fit for his own brand of pokey neurosis. But even with a weak center, Mia Madre manages its share of grace notes, like the small, sweet scene in which Giovanni makes a meal at the hospital for Ada, or the goofy impromptu dance that Barry leads through the set.