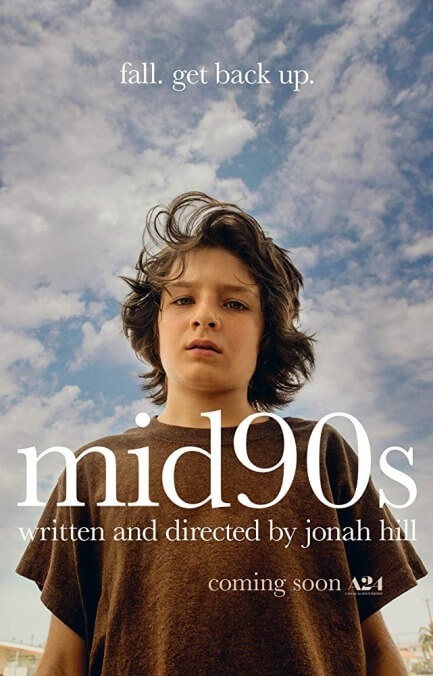

Nostalgia will radiate off the screen for audience members of a certain age almost immediately in Mid90s, when the camera pans across a bedroom, catching sight of Ninja Turtles sheets and a Hulk Hogan pillow before settling on a kid around 13 years old. Stevie (Sunny Suljic) is in front of a mirror, nursing bruises he’s received at the hands of his older brother, Ian (Lucas Hedges), as seen moments earlier. Ian’s bedroom is its own monument to ’90s culture, jockier and more fastidious, with neatly arranged cassettes, CDs, and ball caps, and when Stevie sneaks in to catch a glimpse of his older-brother mystique, Ian serves him a vicious beating. Stevie getting slammed against a wall is the first shot of Jonah Hill’s feature debut, not counting the modified version of the A24 studio logo spelled out in skateboards.

Stevie isn’t a skater, at least not when the movie starts. But he’s lonely, tortured by his brother, and sometimes made uncomfortable by his slightly oversharing single mom (Katherine Waterston), first seen telling her sons about a potential suitor who strikes her as “player-ish.” So when Stevie catches sight of older kids Fourth Grade (Ryder McLaughlin), Fuckshit (Olan Prenatt), and the coolly un-nicknamed Ray (Na-kel Smith) mouthing off to adults and hanging out in a local skate shop where Ray works, their camaraderie and shit-talking looks appealing. Ruben (Gio Galicia), who seems to be filling the role of the youngest and most insecure member of the group, is Stevie’s way in; he’s all too pleased to have someone to order around and receive dirtbag wisdom like “Don’t thank people, they’ll think you’re gay.”

Lines like that, funny for their authentic coarseness, lean into Hill’s comic instincts, honed through years in various Judd Apatow-affiliated ensembles. He also nurtures a talented young cast of kids to give believable, lived-in performances that rarely feel calculated to fill their nonetheless designated roles (the hard-partying screwup, the dumb guy, the gawky new kid). The exception is Ray—not because of the wonderful Smith, who might have the most immediate presence of anyone in the ensemble, but because the character occasionally feels screenplay-engineered to comfort the audience. Despite hanging out with troublemaking skaters, Ray is warm-hearted, level-headed, wise, and reluctant to do drugs, tidily providing the gentle acceptance that Stevie’s brother withholds.

The rest of the skating world is far less idealized, which makes Ray stand out even more. For Stevie, skateboarding becomes a form of self-harm that he can control—and for the more naturally talented Ray, who is trying to build relationships with pro skaters, it’s a potential way out. Stevie, who his new buddies nickname Sunburn, learns to seek acceptance by chasing oblivion, simultaneously putting himself out there and punishing himself for his perceived shortcomings. It’s a provocative idea not fully fleshed out by the movie, which drifts back and forth between thought-provoking immersion and strenuously earnest coming-of-age drama.

Technically speaking, Mid90s is shot in the old Academy ratio of 4:3, but in this context the boxy 16mm images bring to mind television and home video. The smaller frame means that Hill uses a lot of tight one-shots, mixed in with more expressive images like an endless sea of skaters fleeing from cops or a slow push-in on Stevie and Ian having an uncomfortable conversation while playing video games on their couch. The different approaches to image-making don’t always flow together, leaving the movie resembling some bizarre middle ground between a lyrical A24 indie of 2018 and a pan-and-scan VHS of a rougher-hewn indie of the era it depicts.

That’s not necessarily a roadblock for the movie—at least not one that can’t be snaked around. Skate Kitchen, a movie from earlier this year that preemptively compensated for the lack of young women in Mid90s (a few conversations and interactions are pretty much limited to hooking up), had a similar mixed-up vibe. Both movies are instantly ingratiating even as they feel uncertain of how much of their stories should rely on string-pulling incident and how much should be more relaxed and observant. It’s arguable that Hill’s film in particular is mirroring the actual give-and-take between underground and commercial culture that defined so much of the actual ’90s, where homemade skating videos could inspire professionally made music videos, which would then inspire more crappy homemade versions. (Stevie’s pre-skating T-shirts reflect this, too: They’re all underground-aesthetic cartoons like Ren & Stimpy or Beavis And Butt-Head that went on to take malls by storm.)

What Hill hasn’t yet mastered, despite considerable skill as a first-time filmmaker, is how to impose a narrative more quietly, especially in finding the right ending. He also doesn’t seem to fully trust his sense of humor, which after a while feels not just backgrounded but actively suppressed, even as the cutting stays snappy. Mid90s is more than an exercise in refracting the nostalgic radiance of its cultural touchstones. It’s something both rougher and more tender, and still a little bit unformed.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.