Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell: “How Is Lady Pole?”

In episode two of BBC’s adaption of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, the main characters finally meet, quickly perpetuating the narrative that will carry us through to the end of the series. Norrell and Strange come together much sooner in the show than they do in the book, a wise decision on the writers’ part that allows the story to roll along without gathering moss. Altering the structure of Clarke’s book—part one focused on Norrell and part two switched to Strange’s perspective—makes for engaging television, but it comes at the expense of the characters. With the exception of Norrell, they don’t get enough time to develop under this new TV-friendly arrangement.

Upon seeing Strange’s display of magic—the first magic he’s ever seen come from someone else—dowdy Norrell is brought briefly to life. It necessarily humanizes Norrell, as he also continues to demonstrate his selfishness and ignorance, the consequences of bringing Lady Pole back to life in the first episode made clear to him here. Rather than learning from his devastating spell, Norrell feigns ignorance and throws a few temper tantrums, refusing to believe that he, who spent so many years reading about magic in books, does not understand it. His self interest is neatly captured when he barks at the Gentleman that he doesn’t care about the happiness of Lady Pole, but only cares about the success of English magic.

Norrell’s refusal to face the consequences of his magic bodes well for the show, with the darkness at the heart of Susanna Clarke’s source material brought to light in this episode. The growing calamity is highlighted in increasingly distressing scenes of Lady Pole and Stephen, a servant in her house, taken against their wills to the land of Lost Hope every night to join in the fairies’ “revelries.” Lady Pole appears to her husband to be mad, the result of exhaustion and the seemingly random stories she tells. Whenever she tries to speak of what’s happening to her, she is rendered unable to, instead spouting non sequiturs as though her life depended on it. The fairy summoned by Norrell—known as the Gentleman—also takes a liking to Stephen, bringing him along for the Lost Hope revelries.

Why the Gentleman brings Lady Pole and Stephen to Lost Hope is muddled, another casualty of less-than-fleshed-out characters. While the fairy in the book is an odd, fanciful creation, it’s always clear that he’s more childlike than malicious, believing he’s bestowing a real treat on Stephen and not fully aware of how devastating it is to be forced to dance in the fairy world every night. Here he’s played by Marc Warren with a cold slyness, as if he’s cognizant of how horrible it is for Stephen and doesn’t care. It’s hard to tell if anything he’s saying is sincere or not, and that’s a real loss from the character Clarke creates in her book.

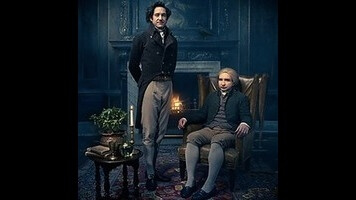

Strange’s character, on the other hand, is a pitch-perfect personification who is in need of more attention, but at least his broad strokes are aptly filled in by a strong performance from Bertie Carvel. He has excellent chemistry with Eddie Marsan, who plays Norrell wonderfully, giving him appropriately pursed lips and a stiff way of moving, jerking into place with a minimal amount of actual movement. He won’t move a muscle if a flick of the eye will do. His stiffness is more pronounced than ever as he meets Strange for the first time, who Carvel makes as loose-limbed and springy as Marsan plays Norrell unflexible and creaky. But Norrell finally becomes animated in this scene, as delighted as a child upon seeing Strange’s display of magic. He breaks into a genuine grin, which, I believe, is the first sign of happiness we’ve seen from him thus far.

This scene is also where the show sparks to life. The friendship and rivalry between the men and all that hinges on their magic gives this story its juice, and the complicated relationship makes for a compelling narrative that churns into action after they meet. Though Norrell is thrilled to discover another practical magician, he clearly doesn’t understand how Strange does his intuitive brand of magic, and there’s deep-seated insecurity and pride that will compel Norrell to his own self-interested ends. Strange’s explanation that his heuristic understanding of magic is like hearing music recalls Mozart and Salieri. If this reference is any sign, the relationship between student and teacher will be a dramatic one.

The divide and difference between the two magicians’ styles of making extraordinary things happen is one of the many reasons the world Clarke created stands out among a sea of magical books. Norrell’s and Strange’s varying magic isn’t really explained here, and in this episode we see that it may not be possible to elegantly cram almost 800 pages of story into seven hour-long episodes. In a clunky expository line, Arabella says she has been married to Strange for a year. This episode certainly doesn’t feel like it’s covered nearly that much time. The story is clipping along, but it’s clear we’re getting an abridged version of it.

What this adaptation does do well is bring the magic to fully realized life, as in the sand-to-horses magic Strange performs. The effects are seamless and the scene spectacular, displaying an imaginativeness on behalf of the showrunner that enhances both the power of the magic on display and the power of the storytelling. The blurry edges that come with human interaction with the Gentleman is also a nice touch used to signal to the viewer that something not-quite-right, something creepy and magical, is taking place. The final scene hints at more devastation to come with the Gentleman’s interest in Arabella, and Norrell is the only one who can see it. With the rest of the cast in need of filling out, it’s Norrell’s show, as much a character study of a selfish, lonely man as it is a story of magic returning to England.

Stray observations:

- Will we get one action-packed scene per episode? Last episode got my heart racing when Vinculus and Childermass read prophesies; this one had me clapping with delight when Strange sent his raging sand horses into the sea. Seems like with an hour, there could be at least one more such scene per episode.

- Speaking of Vinculus, where has he gotten to? Readers of the book will know Vinculus has more to say several years after his first appearance, but the qualities of the television medium allow for him to pop up, maybe with some street magic as our main characters walk by.

- Susanna Clarke said in an interview a month after Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell was published in England that she is working on a sequel focused on the early lives of Vinculus and Childermass. This suggests that they already knew each other in scene from the first episode where they interact.

- There are also one or two fantastic lines per episode. My favorite in this one is Strange barking at Segundus, “I’m rather of the opinion that in England a gentleman’s dreams are his own private concern.”

- A strayer observation than most of my stray observations, but the preoccupation with “English” magic is interesting. Why English only? Are there other nations with other magics? Do other nations matter at all to these people?

- Every time I type “Mr Norrell” as part of the proper title, my heart dies a little.