Joss Whedon was never a feminist

Yesterday, Joss Whedon’s ex-wife, Kai Cole, wrote a gutting letter alleging that Whedon spent two decades lying to her about multiple affairs and using his self-purported feminism as a shield against criticism and scrutiny. Like many women I’ve spoken to, I was sad, but not shocked—maybe a little embarrassed I hadn’t looked more closely at some very clear problems in his work. I love Buffy and Firefly and Dr. Horrible in particular, and I love many of the women characters on Whedon’s shows and what they stand for. I have also been outspoken about the utter bullshit that is Angel’s moment of true happiness being a goddamn orgasm—pleasure, fine, but happiness?—which is to say I’m at least occasionally clear-eyed about Whedon’s work. I’ve been critical, but not nearly as critical as others, like the women of color who have repeatedly pointed out that in Buffy, the first slayer is a black woman depicted as a savage, and her powers are forced upon her by a group of white men against her consent. I am also pretty confident that while straight white men can be great allies in toppling the patriarchy, they will never be the Buffy leading the battle. So why have so few white geek-feminists pried open the cracks in Whedon’s work?

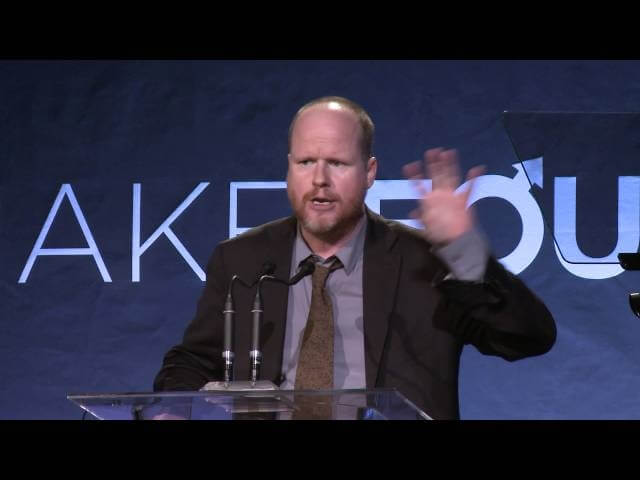

In 2013, Whedon spoke at an Equality Now fundraiser, one of several times over the past decade or so. Whedon spends nearly a quarter-hour picking apart the word “feminist” and why he hates it—in particular, the –ist, which he calls unnatural, something we learn, or something that comes to us. Noah Berlatsky at The Atlantic was one of many who raised an eyebrow at the speech, saying, “This is a speech about the word ‘feminist,’ but there are no feminists in the speech.”

The speech is emblematic of the kind of performative feminism that Whedon’s being accused of. He bulldozes over the fact that, for better or worse, feminism is an –ism. And despite his self-deprecating jokes and satisfyingly barbed nicknames (he suggests referring to misogynists as “pathetic prehistoric rage-filled inbred assclowns”), he doesn’t get to change that. According to Cole’s letter, Whedon’s view of feminism is that it’s simply a list of grievances and inequalities, one that he can overcome with a few great female television characters. And even those characters—like Buffy’s slayerettes or Firefly’s sex worker Inara—are still largely written for the male gaze.

Whedon manipulated the meaning of a word—calling himself a feminist without really understanding what feminism was—and he manipulated his wife. (Whedon has responded to Cole’s accusations with a statement: “While this account includes inaccuracies and misrepresentations which can be harmful to their family, Joss is not commenting, out of concern for his children and out of respect for his ex-wife.”) The problem of manipulative men is well known to women, and that’s why it’s so easy to believe Cole. If you’ve been in an emotionally abusive relationship or otherwise been manipulated by a man you trust, Cole’s letter will sound real fucking familiar. It’s hard to realize you’re being manipulated by somebody you trust—you trust them, that’s kind of the point—and the moment of realization is simultaneously empowering and depleting. You finally see the truth, and the truth punches you in the nose.

And a lot of us trusted Whedon and his characters and, yes, even his performative feminism. His work has plenty of male gaze and women in refrigerators and some narratively pointless rape scenes—it’s all right there, in hundreds of hours of television and film—but boy, it sure is a lot more comfortable to listen to a guy tell you he’s a feminist than listen to a lot of women telling you he’s not. Women are trained to prioritize men; men expect to be trusted. We trust men; men use that to shield bad behavior. I was sexually harassed for four years, beginning when I was 16 years old, by a male boss. I stopped talking about it in public spaces because I got sick of people asking me why I’d let it go on for so long. Aside from the fact that I wasn’t responsible for his behavior, or that I was a kid who didn’t have the vocabulary for what was happening, I also trusted him. He was an authority figure, and an older man, the kind of person I was raised to be polite to and defer to, and he used that trust as a shield for some pretty awful behavior. It’s a commonplace story.

As for Whedon’s bad behavior, or at least the public side of it, it’s no wonder that a lot of women read about it and said, “Well, yeah, sure. Makes sense,” even if, like me, it’s not something you’d really broken apart. Whedon doesn’t get that feminism isn’t an award you earn by writing “strong female characters.” And he can write those characters even as he acts contrary to them—that just means that he’s a good writer, not a good feminist. Cole says that Whedon wrote to her:

When I was running Buffy, I was surrounded by beautiful, needy, aggressive young women. It felt like I had a disease, like something from a Greek myth. Suddenly I am a powerful producer and the world is laid out at my feet and I can’t touch it.

“Beautiful, needy, aggressive young women” are the words of a predator, not a feminist. “It felt like I had a disease, like something from a Greek myth” is just a more poetic way of saying “I couldn’t keep it in my pants.” “The world” isn’t yours for the taking. None of these are words you say if you believe that women are equal, and that we have the right to bodily autonomy, and that we are not things for you to consume and play with. (Hello, Dollhouse.) Feminism isn’t a brand, and it’s not something you can wield to deflect criticism.

I love Buffy and will probably always love Buffy. I have a cross-stitch on my desk of two dinosaurs and the words “Curse your sudden but inevitable betrayal!” I sing along (loudly, terribly) to Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog and get weepy every time I finish. And if I’ve belatedly realized that Whedon was never the feminist he claimed to be, and that I can’t watch his work the same way I always have—that’s okay, and even good. If Whedon is using feminism to shield himself from terrible behavior, then it should poison his work. Whedon is right about at least one thing in that 2013 Equality Now speech, even as its noxious irony is revealed: “You don’t have to hate someone to destroy them, you just have to not get it.”