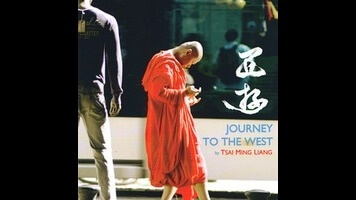

That may sound hopelessly abstract, but Journey To The West is as simple, in its wordless variations on a single visual idea, as a Buddhist parable. The film consists of 14 static shots, all but two of which depict a monk—bald, barefoot, draped in a red robe—moving at tortoise speed, each step taken as slowly as possible. Emerging, early on, from some kind of underground temple, he makes his gradual way across a beach and into modern Marseille. Is he on a spiritual pilgrimage? The silent stranger is based on an actual 17th-century monk, though you won’t learn that from the film. Tsai shoots him from above and below, in close-up and at a great distance. He places him in center frame, allowing a swarm of pedestrians (some mesmerized, some indifferent) to pass around him, and has him wander in the background of shots, visible through open windows and around the edges of the frame. There are times when watching the film is like paging through a Where’s Waldo? book; you scan each crowd scene for a slow-moving red speck.

The monk is played, inevitably, by Lee Kang-Sheng, star of every feature Tsai has ever shot. Journey To The West continues the director’s habit of bringing back old characters—especially those embodied by his permanent leading man—by allowing Lee to reprise a role he occupied in a series of shorts and anthology segments the two made together. Journey, the culmination of this project, introduces a second character, played by that chameleon of French cinema, Denis Lavant. The first image of the movie, in fact, is a close-up of Lavant’s face—half-engulfed by shadows, marked with stubble, and deathly still, save for the flicker of his eyelids and gentle bob of his breathing. He seems vaguely haunted, or perhaps just unfulfilled, at least until a pair of subsequent shots put him on the path of Lee’s “walker.” One of them places Lavant’s slumbering face in the foreground and Lee’s wandering figure in the background, as though the latter were inching into the former’s subconscious. The other, a remarkable display of synchronized movement, suggests that the monk has gained a disciple—or, alternatively, that Lavant’s shape-shifting thespian from Holy Motors has found a new part to play. If there’s a narrative at all here, it’s in the relationship between the two.

Barely a feature at 56 minutes, Journey To The West lacks the sheer emotional pull of Tsai’s greatest films, to say nothing of the deadpan humor that used to enliven his consistently demanding work. There’s also something a little borderline preachy about its juxtapositions, which place this pokey, reverent traveler against the hustle and bustle of the city, possibly to damn the rat race with a Zen alternative. But, oh those compositions: Filming his star from multiple angles, Tsai keeps finding new ways of making one action—a guy walking at a snail’s pace—visually interesting. (His most striking setups include a long scene of Lee descending a staircase, backlit by the heavenly glow of daylight, and an upside-down panorama of metropolitan life, glimpsed through the reflection of a mirrored canopy.) As for the director’s famously protracted takes, they create, in this context, a proper sense of suspended animation, allowing the audience to take it all in, just as the protagonist does. It’s truly meditative cinema—a fitting approach to the leisurely advance of a mute monk. If this does turn out to be Tsai’s swan song, at least he found one fine, final excuse to treat his camera like unblinking eyes.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)