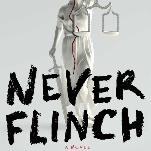

Judith Miller, Stephen Engelberg & William Broad: Germs: Biological Weapons And America's Secret War

On Oct. 12, Judith Miller, a reporter for The New York Times, was on the phone with another writer, hammering out the details of a story they were preparing before deadline, when she casually opened an envelope with a Florida postmark and no return address. The envelope contained a threatening letter and a white powder that scattered over her face, hands, and clothes. Though the substance was later revealed to be non-toxic, the incident required the clearing of the Times building's third floor, which effectively disrupted business, wasted health resources, and spread terror, all for the price of a 34-cent stamp. (If Miller herself was at all shaken by the event, she hasn't shown it. In the days since, her byline has appeared frequently, and, in a recent CNN appearance, she eviscerated an al-Jazeera broadcaster for his network's habit of referring to suicide bombers in the West Bank as "martyrs" and the Sept. 11 hijackers as "terrorists.") The Times incident was a classic example of an attack on the messenger: An expert on the Middle East and the former Soviet republics, Miller and two colleagues (Stephen Engelberg and William Broad, who specialize in national security and science, respectively) had just published Germs, an urgent and incisive exposé on the secret past and imposing future of biological weapons. The book offers some scant comfort regarding America's current bout with bio-terrorism: With the potential for genetically manipulated pathogens and more sophisticated delivery systems, the situation could be a great deal worse. At once chilling and reassuring, though the balance tips decidedly toward the former, Germs presents a thorough and accessible account of the largely covert development of biological weapons and surveys an unstable international landscape that threatens devastation on a massive scale. The book opens with the first act of bio-terrorism ever committed on U.S. soil, an obscure outbreak of salmonella poisoning inflicted on the small town of The Dalles, Oregon, in 1984. In a sinister plot to gain political clout in the county by incapacitating its citizenry, the Rajneeshee religious cult used homegrown strains to contaminate several local restaurants, resulting in the hospitalization of more than 750 people. No one died, but the virtually unreported incident was symbolic of two of Germs' major points: Biological terrorism can happen in America, and the country's persistent failure to confront the issue may result in serious consequences. From there, the authors detail the complex, five-decade history of germ development around the world, with a special focus on the Cold War buildup between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. As the U.S. tailed off its research in accordance with the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, a treaty that banned biological weapons, the Soviets stepped up a hidden program of astonishing sophistication and proportion. In the book's most frightening chapter, an American inspector visits a facility at Stepnogorsk that housed 10 four-story-high fermentation vats, each capable of manufacturing enough anthrax spores per year to wipe out the entire U.S. population. This leads the authors to more pressing questions: What happened to the hundreds of scientists—many of whom were skilled in producing recombinant DNA germs that resisted vaccines and antibodies—who lost their jobs after the Cold War? Did rogue states or well-funded terrorist organizations recruit them to develop anthrax, botulinum, smallpox, and other diabolical afflictions? Germs sounds an important warning that America is "woefully unprepared" to defend itself against large-scale biological warfare, even as it notes the extreme difficulty of weaponizing disease. For now, it's a small reassurance that the threat is contained in an envelope.