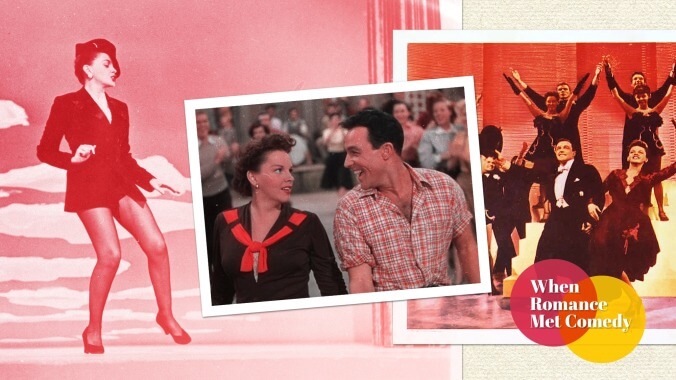

Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, and the bittersweet joys of puttin’ on a show

Image: Photo: BettmannPhoto: LMPC

No one knew it at the time, but Summer Stock marked the end of an era for Judy Garland. The 1950 musical comedy was the last film Garland made for MGM, the studio that had defined her career since her breakout as a 15-year-old singing to a photo of Clark Gable in Broadway Melody Of 1938. In the studio-driven days of classic Hollywood, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer branded itself as the home for stars and musicals. And from the late 1930s through the late 1940s, Garland was one of the studio’s biggest icons, anchoring big budget Technicolor hits like Meet Me In St. Louis, The Harvey Girls, and, of course, The Wizard Of Oz. At least until the nonstop workload brought her crashing down to earth.

In some ways, Summer Stock feels like an ignobly small-scale end to Garland’s run at MGM. The plot is—to quote the film itself—pure hokum. Garland is Jane Falbury, a tenacious young woman trying to keep her struggling farm afloat with the help of her no-nonsense housekeeper, Esme (frequent Garland co-star Marjorie Main). Gene Kelly is Joe Ross, the theater director who shows up to rehearse his new musical in the Falbury barn at the invitation of Jane’s flighty kid sister, Abigail (Gloria DeHaven), who just happens to be his girlfriend and star performer. Only it turns out Abigail didn’t clear the plan with Jane first. So tensions (and comedy) flare as a bunch of theater kids try to adjust to life on a farm, while Jane realizes she just might have grease paint in her veins after all.

Even in 1950, Summer Stock felt old-fashioned. At a time when Kelly was pushing the movie musical format into inventive new heights with films like On The Town and his upcoming An American In Paris, Summer Stock’s simple premise was positively prosaic. But Garland needed something small-scale to ease her back into work. She had just spent three months in rehab being treated for addiction and exhaustion after having been publicly fired from Annie Get Your Gun. The original idea was to reunite Garland and Mickey Rooney for a throwback to the “let’s put on a show!” comedies they’d made famous in the late ’30s and early ’40s. But since Rooney was no longer a box-office draw, MGM turned to Kelly instead. And though Kelly wasn’t a fan of the script, he jumped at the chance to help out Garland. As he’d later put it, “We loved her and we understood what she was going through, and I had every reason to be grateful for all the help she had given me.”

In many ways Kelly was just returning a favor. He first worked with Garland on 1942’s For Me And My Gal, when he was a 29-year-old Broadway star making his first-ever feature film and she was a 19-year-old movie star making her 15th. The erstwhile Dorothy Gale was Kelly’s champion on the set. She helped him adjust his acting style for the camera and supported him in disagreements with director Busby Berkeley. It was an experience Kelly never forgot. He reteamed with Garland again in the bombastic 1948 musical comedy The Pirate, and showed up in full support mode on Summer Stock. For a while, the friendly environment seemed to bolster Garland. But—as was the case with so much of her career—studio pressure to lose weight sent her spiraling back into destructive cycles. Production ballooned into a six-month shoot plagued by Garland’s severe physical and mental health problems.

Yet what’s most remarkable about Summer Stock is how none of those behind-the-scenes issues are visible onscreen. In its final cut, the film is an effervescent, delightfully corny salute to the theater in which Garland keeps up with Kelly step for step, ending her MGM run with her iconic performance of “Get Happy”—a brassy, sexy highlight of her entire career. From the opening scene of Garland belting out “If You Feel Like Singing, Sing,” Summer Stock is bursting with life. The next production number sees an overall-clad Garland riding a tractor down a country road, kicking her leg in the air as she shout-sings, “Howdy, neighbor! Happy harvest!” It’s the sort of sunnily surreal thing that could only exist in a movie musical.

As evidenced by that tractor scene, Summer Stock is a gloriously silly film. Its “theater kids meet country squares” premise lets it make fun of both groups in equal measure. There’s a hilarious montage of Joe’s troupe failing to perform even the most basic farmyard tasks, which really brings me back to my theater school days. Every character actor is having an absolute blast, especially Phil Silvers, who seems to make Kelly laugh in every take. And Summer Stock is one of those classic movie musicals in which the show they’re rehearsing makes absolutely zero sense (particularly once you get to a dog-filled hillbilly number), which somehow only makes the whole thing more charming.

But there’s a level of poignancy underneath the hokum, too. The value of revisiting Summer Stock’s old-fashioned formula with actors in their late 20s and 30s is that the material takes on new emotional weight. These aren’t teens putting on a show for fun but adults making personal and professional decisions that will affect the rest of their lives. In their best scenes, Kelly and Garland lean into the more dramatic side of the featherlight material, as does director Charles Walters, a dancer-turned-choreographer who’d known Garland since he was her onscreen dance partner in 1943’s Presenting Lily Mars.

Walters was chosen to helm Summer Stock because he’d worked so well with Garland as the director of her 1948 hit Easter Parade. Reflecting on Garland’s Summer Stock troubles, Walters recalled, “Gene took her left arm and I took her right one, and between us, we literally tried to keep her on her feet.” Though Walters wasn’t thrilled with the old-fashioned script either, he did his best to elevate the material to meet Garland and Kelly’s talents. There’s one gorgeously romantic long shot in Garland’s ballad “Friendly Star” where Walters pulls back the camera to reveal Kelly sitting and listening to her mournful love song, before circling back around to Garland again.

At its best, Summer Stock’s stripped-back simplicity feeds into the film’s celebration of the magic of live theater. In the movie’s most touching scene, Joe takes Jane on a late night tour of his newly constructed stage while explaining the power of musical theater as an art form. “We’re trying to tell a story with music and song and dance and… well, not just with words,” Joe explains. “For instance, if the boy tells the girl that he loves her, he just doesn’t say it, he sings it.” “Well, why doesn’t he just say it?” Jane asks. “Why?” Joe responds with Kelly’s signature sly smile. “Oh, I don’t know, but it’s kind of nice.”

It’s not really an explanation, but for people who love musical theater, it’s the only explanation there is. “It’s like electricity,” Joe explains of his love of opening night. After having Jane take a whiff of grease paint, he only half jokes, “Go easy. That’s very potent stuff. You smell it once too often, it gets way down deep inside you. You can wipe it off your face, all right. But you’ll never get it out of your blood.” It’s a scene that lands with extra resonance because it reflects the attitude of its two stars. Garland and Kelly were lifelong workhorses who redefined the movie musical—her with her brassy vocals and naturalistic acting; him with his athletic, highly artistic approach to dance. Summer Stock’s pared-back style even inspired Kelly to create one of the most simple, evocative dance routines of his entire career. With just a squeaky floorboard, a few pieces of newspaper, and an empty stage, Kelly crafts a five-minute sequence that’s every bit as compelling as his biggest production number.

Jane and Joe get a conventional rom-com love story that’s beautifully acted by Garland and especially Kelly, whose real-life admiration for his co-star beams through in every one of Joe’s love-struck looks. But there’s a broader feeling of love for musical theater that permeates the entire film, too. This is as much a story of Jane falling in love with performing as it is about her falling in love with Joe. And Garland has perhaps never been funnier than she is in the scene where a frazzled Jane—now roped into starring in the musical—chews out her nerdy fiancé Orville (a hilarious Eddie Bracken) as she prepares to rehearse her onstage entrance another “forty, fifty… a lotta of times.” Jane’s salt-of-the-earth farmer gumption translates into exactly the sort of work ethic Joe expects from his cast (and that Kelly famously demanded in real life as well). It’s a scene that shows off Garland’s complete mastery of subtle comedic timing, which is maybe the most under-appreciated of her vast repertoire of skills.

It’s of course important to acknowledge the tragedies of Garland’s life—particularly when so many of them stemmed from the abuses of an inhumane studio system and a judgmental patriarchal culture, both of which still exist today. (Nearly every retrospective on Summer Stock includes a lengthy discussion of Garland’s onscreen weight fluctuations, which is truly the least interesting framing imaginable for her fiery performance.) But it’s also important to acknowledge what Garland brought to her art, too. In Summer Stock, she makes Jane as funny and tenacious as any of her best characters. And Garland was also crucial in shaping the film’s breakout musical number, “Get Happy,” which was added shortly after production wrapped when MGM realized the movie was missing a big final showcase for its leading lady.

Garland chose the song, suggested reusing a costume that was cut from Easter Parade, and requested that Walters stage and choreograph the number himself. (Nick Castle is the credited choreographer on the film, although Kelly choreographed several of his own numbers as well.) The result is one of Garland’s most iconic musical performances ever, one that’s been homaged endless times over the years because its simple, sultry staging is so effective. With each tip of her fedora and swivel of her hips, Garland conveys the sense of a performer in full command of her craft.

Garland and Kelly both had career highlights ahead of them after Summer Stock. He would reach his creative pinnacle with the one-two punch of An American In Paris and Singin’ In The Rain, while she would return from a four-year acting hiatus to deliver perhaps her best performance in 1954’s A Star Is Born. But Summer Stock is a bittersweet sendoff to Garland’s MGM career and her onscreen partnership with Kelly. The ability to forget your troubles and get happy is a gift that Garland and Kelly have given to audiences for decades—one that’s especially welcome at a time when the world’s troubles seem scarier than ever. In its own goofy, homespun way, Summer Stock is a celebration of musical theater’s ability to provide a beam of sunshine on a cloudy day, and a tribute to the artists who work so hard to make it look effortless.

Next time: Let’s celebrate 15 years of Failure To Launch.