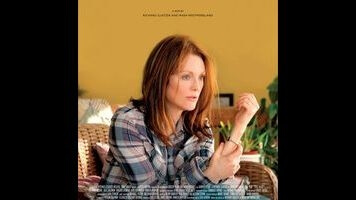

Rarely letting on how much time is slipping by between scenes, writer-directors Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland (Quinceañera, The Last Of Robin Hood) frame the movie around routines and repetitions. Alice jogs every day around the Columbia campus, until she doesn’t; she goes for walks on her own, until she can’t; she’s able to make her own way around the house, until she pisses herself looking for the bathroom. It sounds rigidly schematic, but isn’t, because instead of foregrounding structure, Glatzer and Westmoreland focus on Moore’s nuanced performance—never more clearly than in the long, locked-in close-up that covers her first visit to the doctor—and on her character’s changing relationships with her husband, her children, and to her own sense of self.

Parenthood, aging, marriage, a work-life balance—these are common grown-up anxieties, which the movie magnifies, using Alice’s disease as a kind of catalytic agent. (It’s no coincidence that the film opens on her 50th birthday, with her condition still undiagnosed, but already showing its symptoms.) She isn’t an easy person to begin with; she can be overbearing and bullheaded, and she makes no secret of her disappointment in her youngest daughter, Lydia (Kristen Stewart), who has moved out to L.A. to try to make it as an actor. Her marriage to John (Alec Baldwin) is built on mutual values of independence; both have committed to their academic careers, and he refuses to put his on hold.

What these relationships and anxieties have in common is that they’re all motivated by expectations about the future. As Alice’s condition worsens, the future recedes, disappearing even more quickly than the past. In many ways, Still Alice’s big subject is the issue of what gets left behind when all the things that define a person—past, future, independence—crumble away. Its title might as well have a question mark at the end of it.