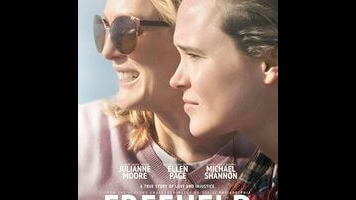

Julianne Moore lends dignity to award-season material with Freeheld

Based on a rousing true story, Freeheld focuses on a dying woman crusading for gay rights, and features an imposing cast of Oscar nominees. But it doesn’t quite feel like the prestige pictures that blow through theaters this time of year; it’s a drama often dignified by its workmanlike approach, one that feels relatively judicious with its uplift. For one thing, the movie mostly refuses to sentimentalize its central character’s terminal illness. Veteran detective Laurel Hester (Julianne Moore) has just remodeled a house with much-younger gearhead girlfriend Stacie Andree (Ellen Page) when she’s diagnosed with late-stage lung cancer. Laurel counters any and all shows of we’re-gonna-fight-this solidarity with a stiff dose of realism: No, we’re not; the survival rate is almost vanishingly small.

The ins and outs of work also get some screen time in Freeheld, and while the film is not always sophisticated on the topic—the garage that employs Stacie, for example, is sketchily realized—the professional details nonetheless help to ground the proceedings. It’s Laurel’s dream to become the first female lieutenant in Ocean County, New Jersey—the film opens with her on the job, in the middle of a boardwalk drug sting. The bust puts her and her wise-cracking partner, Dane Wells (Michael Shannon), on the path to solving a double homicide, a thread that the film periodically picks up, but never takes the time to make wholly intelligible. The case mostly serves to establish that Laurel is good at what she does. A decade’s worth of murky off-the-book procedurals like the now-playing Sicario have conditioned viewers to brace themselves when an officer of the law turns off the video camera during a closed-doors interrogation. But when Laurel takes that particular action here, there’s no beating in store. Far from it—the detective has something of a heart-to-heart with the woman in custody, who afterward finally fingers two bad-guy acquaintances, providing a big break in the investigation. Indeed, the sole professional liability Laurel seems to have is her sexual orientation. She’s vigilant about keeping this secret from the rest of the force, only informing Dane of her domestic partnership when he shows up unannounced to deliver a housewarming rhododendron and finds Stacie tending the garden.

Freeheld, directed by Peter Sollett (Raising Victor Vargas, Nick And Norah’s Infinite Playlist) from a screenplay by Ron Nyswaner (Philadelphia), soon strikes its keynote as a political drama, giving a thorough, if not always balanced, sense of the local-level factors at play. A pushback—first small, then substantial—comes after the county’s governing body, a board of five “freeholders,” denies the recently diagnosed Laurel’s request to leave her pension to Stacie upon her death. The loyal but gruff Dane steps up, helping the couple strategize a process of appeals and lobbying a reluctant police force for support. And Steve Carell breezes in as if from another movie, going too heavy on the can-do attitude as an activist who sees in Laurel’s plight an opportunity to further the broader gay-marriage cause. The caricatures unfortunately don’t stop there: The obstructionists on the freeholder board are depicted as a backroom boys’ club, with a new member, played by Josh Charles, as its sole glimmer of conscience. These elected officials remain largely unmoved by the increasingly emotional public-forum speeches exhorting them to reconsider their position, though they certainly don’t appreciate the gathering shitstorm of bad press.

These speeches, all the more stirring for being so short and to the point, form the emotional core of the last third or so of the film, and here Moore in particular rises to the occasion. The ravages of Laurel’s disease are made especially apparent through her pleas to this panel of old white guys; you can almost feel the energy leaving Laurel’s body with every shallow wheeze of a syllable. Page, meanwhile, delivers a doozy when she finally takes the podium, but her performance is most moving for the quiet desperation with which she plays Stacie’s initial denial of Laurel’s deteriorating condition. Such touches distinguish Freeheld, whose central couple—along with Shannon’s Dane, glowering through his every act of kindness—come to seem like real people just struggling through a tough situation. Sollett’s straight-ahead style (this looks like nothing so much as a network-TV original movie from just before the period it depicts) gives them ample room to breathe. Nowhere the film goes is unexpected—right down to the pre-closing-credit montage of photos of the real-life Stacie and Laurel, and the title card matter-of-factly celebrating last year’s big gay-marriage victory—but the plainspoken Freeheld charts a mostly admirable course there.