Jurassic World goes back to the park, but the danger is missing

“No one’s impressed with dinosaurs anymore,” says harried middle manager Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard) on what will quickly prove to be the most stressful, disastrous day of her life. Claire’s talking about Jurassic World, the fully functioning, dino-exhibiting amusement park she runs, and how the waning awe of attendees has forced the owners to cook up some bold (a.k.a. foolishly dangerous) new attractions. But she could also be talking, in a fourth-wall-breaching sort of way, about the very movie in which she’s unwittingly starring. Maybe dinosaurs aren’t enough to satiate audiences anymore. Maybe, some 22 years after Steven Spielberg brought those mighty animals back to life, what we really demand is dinosaurs crossed with other dinosaurs.

Jurassic World, a goofy and fitfully entertaining summer movie, understands and even winks at its place in the pecking order of blockbuster sequels. Like its predecessors, it’s been engineered to up the audience-courting ante. What’s scarier than a Tyrannosaurs rex? The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Spielberg’s own (underrated) sequel, doubled down on the rex, unleashing not one, but two of the hungry behemoths. And in Jurassic Park III, the big guy was replaced by an even larger, faster, and meaner alpha predator. Jurassic World goes further, into the realm of genetic modification, and emerges with a deadly new designer species—a pale-white lab experiment gone wrong, a not-so-gentle giant with camouflage flesh and a keen intellect. It’s a ridiculous direction for the series to take, but at least the filmmakers exhibit some self-awareness: As a comic-relief control room jockey, New Girl’s Jake Johnson gets to sport an original JP T-shirt and make nostalgic cracks about how the first Jurassic Park (the place itself, wink wink) didn’t have to create genetic hybrids to sell tickets.

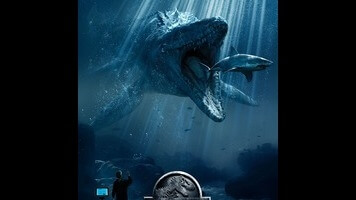

What the film’s four credited screenwriters also understand is that part of the appeal of Michael Crichton’s original premise, reconfigured from his earlier Westworld, was the sight of a corporate vacation destination gone horribly wrong. Putting the park back into Jurassic Park, this fourth entry is never more fun than when crosscutting around its island setting, and watching as various employees run damage control after their absurdly vicious creation—Indominus rex, a name even the film’s characters mock—escapes captivity. Under pressure from her mogul boss (Irrfan Khan, heir to the throne of Richard Attenborough), Howard’s heroine attempts to contain the threat without evacuating the park. Guess how well that goes? The trouble isn’t all dino-related: InGen, the Weyland-Yutani of the Jurassic Park universe, wants to weaponize the Velociraptors, with an oily Vincent D’Onofrio on site to make the corrupt case. Guess how well that goes?

Speaking of raptors, nature’s finest killing machines just keep getting smarter. They’ve now learned to take commands, but only from someone with the right dino-whispering moves. Enter Owen Grady, a sarcastic, motorcycle-riding maverick trainer, played by Hollywood’s hunky funnyman of the moment, Chris Pratt. Owen’s something of a hybrid himself, infused with the dismissive snark of Jeff Goldblum and the great-white-hunter gravity of the original’s Muldoon, with a dash of Indiana Jones added for good measure. He’s great as a voice of reason, less so as a love interest: Howard, in the fairly thankless leading role of an uptight workaholic, spends most of the movie getting put in her place by her studly costar; it’s no real wonder sparks don’t fly between them. Still, this retrograde Romancing The Stone subplot is much preferable to scenes of Claire’s nephews, teenage Zach (Nick Robinson) and preteen Gray (Ty Simpkins), getting some brotherly bonding in while trying not to be eaten. They’re no Lex and Tim.

Much more than the other sequels, Jurassic World recalls the original, working in some of the iconic locales of its iconic predecessor and leaning hard on that rousing John Williams theme. And yet director Colin Trevorrow, making the leap to the big-budget big leagues after Safety Not Guaranteed, can’t match the more tactile thrills of Spielberg’s seminal summer movie. Trevorrow’s set pieces—a dive-bombing flock of pterodactyls; a supremely ridiculous but crowd-pleasing climax—are lively but never remotely terrifying. The film desperately wants for the danger, the white-knuckle excitement, of raptors in the kitchen or T. rex in the rain. For all its winking callbacks, Jurassic World is a modern blockbuster through and through: While the first Park skillfully mixed and matched animatronics with CGI, resulting in what still feels like the ultimate special-effects movie, this expensive retread seems content placing its flesh-and-blood stars against a rotating green screen of digital attractions. Technological advances aside, it looks much faker than its ancient ancestor. As Pratt puts it here, “Maybe progress should lose for once.”