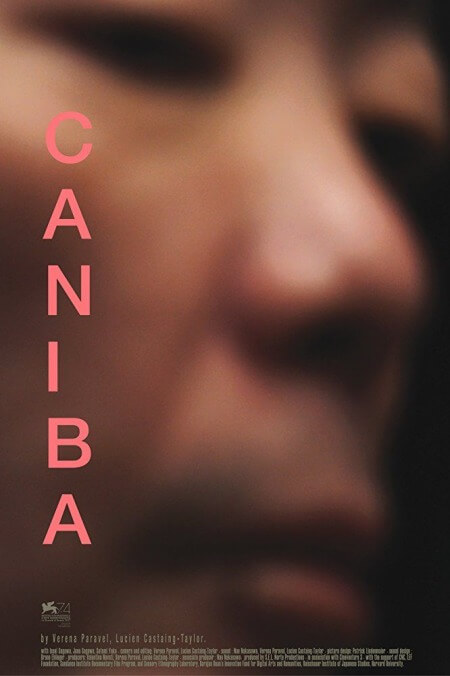

No horror movie hitting theaters this October could hope to inspire as much nausea as Caniba does. It’s the new documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel, Harvard-trained researchers who specialize in a queasily up-close-and-personal school of nonfiction. Their last movie, the remarkable Leviathan, brought durable and lightweight cameras aboard a commercial fishing vessel, plunging viewers into that messy, visceral industry: the flopping fish, the crashing waves, the flocks of hungry birds circling above. (It really put the sensory in Sensory Ethnography Lab.) Caniba’s perspective is less dynamic and more stationary, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel keeping their lens locked on the face of their interview subject. That subject, however, happens to be a real-life cannibal, and his desires—indulged once but not necessarily satiated—are an ocean every bit as dark, violent, and alien as the real one of Leviathan. Certainly, viewers may feel a kind of seasickness, their stomachs doing somersaults during this supremely discomfiting movie.

Issei Sagawa, whose expressionless visage occupies most of Caniba’s 97 very long minutes, was a student of the Sorbonne in the summer of 1981, when he murdered a Dutch classmate, Renée Hartevelt, and then spent two days consuming parts of her body. Caught trying to dispose of what he hadn’t eaten, Sagawa got off on an insanity plea and returned to his home country of Japan, where he faced no further legal consequences. In fact, the crime afforded him a kind of celebrity, which he parlayed into a literary career, erotica gigs, even a tenure as a food critic. Little of this is even mentioned by Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, who opt to let their talking head do all the talking—that is, when he feels like saying anything. Caniba consists primarily of extreme close-ups on his blank stare, framed so tightly that his flesh fills the whole screen. His perpetual calm is undeniably unnerving, even profoundly creepy, though that’s certainly exaggerated by the invasive, suggestive way he’s filmed. Naturally the first thing we see and hear him doing is eating, very loudly.

It’s not much of an interview. Sagawa speaks little of the murder, and when he does open his mouth (an orifice the filmmakers ghoulishly focus on, amplifying every gulp and slurp) it’s to offer less-than-illuminating insight into his dark compulsions: “Cannibalism is very much nourished by fetishistic desire,” he remarks, as if reciting from a medical journal on his sickness. Reenactments would be beyond tasteless, but Caniba finds a substitute, zooming in on Sagawa’s self-published Manga—a frame-by-frame account of the crime, which might be even more revolting than any live-action dramatization would be, as it presents the grisly events through the lurid, stylized prism of his sexual fantasy.

Now in his 60s, Sagawa suffers from an unspecified illness, and is cared for by his brother, Jun, who Castaing-Taylor and Paravel often leave off screen or in the background of the frame. He is, in most respects, a more accommodating and revealing interview subject. Tittering nervously throughout, he expresses a constantly shifting attitude towards his brother, bouncing from fascination to repulsion and back again, and the film gets some uncomfortable pathos out of the sibling relationship. Jun, as it turns out, has a compulsion of his own: a lifelong masochistic addiction to self-harm—cutting, stabbing, burning his own arms, a ritual the film of course captures in graphic close-up. It’s tempting, at this point, to wonder about some shared, formative trauma, but Caniba finds an inconclusive dead end in their past; their childhood was supposedly idyllic (“Disney” is the word Jun uses), and innocuous home-video footage offers no hints of anything that might “explain” either man’s violent fetish.

Maybe the lack of an explanation is the whole point. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel often get so close to Sagawa’s skin that they seem to be trying to push through it, to move through his pores and into his brain, to put his unknowable mind on full display. But seeing isn’t understanding, and for as much as Caniba fills the screen with his image, it can’t make meaningful sense of his psychology or get to the bottom of his urges or shine any new light on the unspeakable horror of what he did. (Jun claims the two brothers share a love of Renoir, but the film views Sagawa as more of the old cliché of a Monet, in that viewing him up close isn’t especially enlightening or pleasant.) In its cold but leering curiosity, Caniba actually flirts with dehumanizing its subject, fixating on his flesh as obsessively as Sagawa fixated on his victim’s—and that, too, could be the point. But the results aren’t so far removed, in practice if not intention, from a queasy carnival attraction, exploiting a perverse fascination with the man as surely as the pornographers who paid him for his cameo appearances. “I can’t stomach this anymore,” Jun eventually remarks, as his brother pages through his illustrated confession. That makes all of us.