Just in time for Independence Day, The First Purge pulls more thrills from America's ills

Are the Purge movies the crude, sick political parables our crude, sick political age demands? Set in an alternate United States where, for 12 hours once a year, all crime is legal, these dystopian B-movie actioners create a grotesque funhouse reflection of Paul Ryan’s dream for America, imagining a version of the nation where the rich literally prey on the poor, waging war on the 99-percent with shotguns and knives as well as unjust laws. The First Purge, a prequel that looks back on the night the titular tradition was born, doubles down on the social commentary and blunt topicality of its predecessors, peppering the urban anarchy with overt references to white-nationalist violence. It’s all about as subtle as the futuristic costume-ball dress code established in the lame home-invasion thriller that launched this franchise. But maybe subtlety is pointless at a time when science fiction has to hustle just to keep up with the compounding cruelty and insanity of American life.

It’s always been a little hard to buy the nightmare logic behind the Purge’s conception—namely, that one night of unrestricted lawbreaking would curb crime by letting everyone just get every violent impulse out of their system, never mind that not every crime is one of passion. But that skepticism is baked into The First Purge, which traces the practice back to an isolated experiment conducted across Staten Island. With the political backing of the New Founding Fathers Of America, the ruling third party of the Purge universe, Dr. Updale (Marisa Tomei) tests her theory about giving national bloodlust an official outlet. Not that she’s got too firm a grasp on the scientific process: Paying locals not just to stay put during the 12 hours but also to actively participate—with more money awarded to those who “purge” heavily—might kind of skew the results, no? Meanwhile, the politicians who have sanctioned this consequence-free mayhem have their own motives, though one has to wonder if filming the action, via computerized contact lens that give each Purger a set of cool glowing eyes, might actually turn a horrified public against it.

This is the first film in the series written but not directed by James DeMonaco, who apparently exhausted his interest in turning city streets into smoky, underlit battlegrounds. But even with Gerard McMurray (Burning Sands) now behind the camera, DeMonaco’s fingerprints are all over The First Purge. His two previous sequels, Anarchy and Election Year, didn’t just open up a dangerous, outside world only teased by the original; they also abandoned its white suburban milieu, shifting focus to an ensemble of mostly nonwhite characters, plus a stoic ex-military badass played by DTV veteran Frank Grillo. Grillo’s nowhere to be found in The First Purge, which passes full protagonist duties to a cast made up entirely of black characters: headstrong activist Nya (Lex Scott Davis), who leads protests against the experiment; her teenage brother Isaiah (Joivan Wade), who’s started working the corner to help them get out of the projects; and her ex-boyfriend, the slick drug kingpin Dmitri (Insecure’s Y’lan Noel), whose simmering guilt over “destroying the community 365 days a year”—as Nya scorns him—sets up an inevitable redemption arc. Not since George Romero’s first run of Dead movies, perhaps, has a horror franchise so consistently adopted the perspective of marginalized Americans.

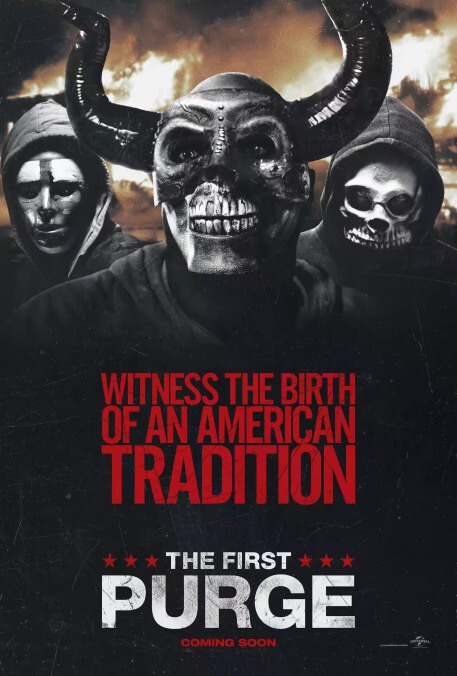

Part of the fun of the Purge movies is how thoroughly DeMonaco constructed his Twilight Zone America, with a surplus of ideas as to how the country might be reshaped by its annual bloodletting. Because of its origin-story approach, The First Purge can’t indulge as heavily in such details, though, amusingly, the aesthetic of the Purge—call it The Warriors meets Slipknot—emerges almost fully formed within minutes of the commencement sirens. Of course, maybe going back in time to a less fantastic version of this premise is polemically crucial: Has the world of The Purge been adjusted to more closely assemble the real America or has the real America now inched closer to the world of The Purge? Even more so than in Election Year, which opened mere months before the nastiest of November surprises, DeMonaco echoes our terrible now: a massacre at a black church, an army of hooded Klansman joyriding across the island, a platoon of white cops leaving a trail of black bodies across an empty baseball field. Wringing genre thrills from headline atrocities, The First Purge is at once crass and provocative in its timeliness—in Blumhouse’s toolshed, it’s the sledgehammer to Get Out’s scalpel.

Still, it’d be hard to deny the film’s political conscience. If the previous Purge movies sometimes flirted with suggesting that Americans of all walks might genuinely jump to unleash their murderous id, The First Purge goes out of its way to imply the opposite: When Staten Island opts to use its freedom to party instead of kill, the government sponsors step in to fabricate crime statistics in the most direct way imaginable. Even the one genuine neighborhood bogeyman, a ridiculous crackhead psychopath dubbed Skeletor (Rotimi Paul), is presented as a threat facilitated and even condoned by the New Founding Fathers (a political party revealed, pointedly, to have been endorsed by the NRA). Ultimately, the real villain of The First Purge is a government-hired (and explicitly Anglo) army of mercenaries, as faceless as the invading hive-mind forces of John Carpenter’s Assault On Precinct 13, shooting a bloody path across a predominately black community. And that lends a certain righteous charge to the film’s action-packed crescendo: a kind of Blaxploitation Die Hard riff, with Noel’s martial-arts crimelord going full John McClane, white tank-top and all, in the narrow hallways of a project building under siege. Most horror movies channel contemporary anxieties. For a good hour and a half, this one at least tries to cathartically purge them.