Justified: “Fate’s Right Hand”

The essential issue with the last season of Justified—and it’s one that could only properly be seen in hindsight—was that there just was not enough story for 13 episodes. As I discussed in the review of last year’s finale, the show needed to rebuild Raylan after he crossed the line in defense of his family, and it needed to bring Ava and Boyd low enough that each would seriously consider a future without the other. As tonight’s excellent season premiere suggests, that new status quo was absolutely one worth working toward, particularly as Justified begins its endgame, but all the business with the Crowes and the last gasps of the Detroit mafia never coalesced into an entire seasons’ worth of compelling narrative. Even an insufficiently epic overarching narrative need not have represented an insoluble problem, as the real problem ended up coming from the other direction: To fill time, Justified ended up expanding stories and playing them out over multiple episodes, when most would have been better served as episode-specific plotlines. The result was a season that could never get a good handle on its own pacing and, worse, on which of its stories should actually carry the highest stakes.

From the outset, “Fate’s Right Hand” is a far more confident installment of Justified than pretty much anything that aired last season. There’s a definite sense that the show is consciously returning to its core strengths, with Boyd’s resumption of his bank-robbing career marked by a lengthy pre-credits sequence in which he prepares to go back to his work, maybe even his calling. It would be much too much to say the characters have stopped lying to themselves, but this season premiere finds the characters far closer to their true selves than they have been in a long time. This episode is sharp and crisp in its storytelling in a way that eluded too much of the previous season. Some of that is down to the show using the bare minimum of ancillary characters—Garret Dillahunt’s mysterious stranger is the only significant addition here, and he is only a minor player in his debut—and keeping the focus tight on Boyd, Ava, Raylan, and that poor lost soul Dewey Crowe. The other crucial factor is that “Fate’s Right Hand” recognizes the best narrative scale for each of its characters’ plotlines, and that allows Justified to build and sustain storytelling momentum as the new season begins.

We may as well begin with Dewey Crowe, who finally reaches the end of his long, winding, deeply idiotic road. I wouldn’t say that “Fate’s Right Hand” exactly foreshadows Dewey’s murder at the hands of Boyd, but that may well be because Justified, for all its willingness to engage in high body counts, has always been a little cozy with its favored characters. Dewey has always been the show’s comic relief, and it was earth-shattering enough last season when he actually did manage to kill Wade Messer. Dewey Crowe’s status as the most ridiculous would-be criminal in Harlan appeared to grant him privileged status, a criminal who could always be counted on to be caught—and, thanks, to the inimitable way Raylan would catch him, subsequently released—before he did anything truly unforgivable.

“Fate’s Right Hand” engages in some fun, self-aware exploration of that very notion: Dewey Crowe gets released (complete with 1,000-foot restraining order against Raylan!) despite charges of murder and drug possession, mostly because the justice system can’t take him seriously as an actual criminal, he uses his apparent narrative invincibility to blow right past the Kentucky state police, and his final downward spiral is motivated in part by his sad, dawning realization that he can never be anything more than an underwear-toting decoy. His death only comes as a shock because I hadn’t thought Justified would be willing to pull that particular narrative trigger. Yes, the fact that it’s the final season makes a difference, but this is still the kind of development that the previous season might easily have spent three or four episodes ambling toward, losing the significance of Dewey’s fate along the way. As a single-episode story, Dewey Crowe’s death manages some real pathos, as he finally becomes quite literally too dumb to live. Of Mice And Men provides the obvious inspiration for what Boyd does to Dewey, as e offers one last glimpse of a future—albeit one glimpsed by miners from decades past—that neither of them will ever know: Boyd because he knows Harlan is dying, and Dewey because Boyd is hastening said death by killing most of the people left there.

While Dewey’s story is necessarily limited to this episode—unless we’re about to start dealing with the Ghost of Dewey Crowe, which, yes please—Boyd’s story is the one that appears most obviously set to span the entire rest of the show’s run. As brilliant a criminal as Boyd Crowder undoubtedly is, “Fate’s Right Hand” reminds us that he’s still an Elmore Leonard criminal, and it was only a matter of time before he became tempted by the siren song of the last big score. The actual mechanics of the bank heist are hugely entertaining, mixing together Boyd’s trademark love of urbane rhetoric with sudden bursts of extreme violence. The eventual reveal that the gang apparently heisted nothing of value suggests some intriguing narrative possibilities to carry the next few episodes: Either Boyd’s associates have already begun betraying him—which is inevitable, but probably not happening quite yet—or this is a much more complicated score than anticipated. Either way, Boyd’s story already appears to contain an intricacy of plotting that eluded much of his story last year, and Boyd is rarely more dangerous than when people think they’re outsmarting him.

Few people know that quite as well as Ava, who settles into her precarious role as criminal informant against Boyd. As great as that season-closing meeting between Raylan and Ava was, “Fate’s Right Hand” quickly points out the impossibility of the situation: How could anyone hope to fool one as sharp as Boyd long enough to get useful information? Raylan offers a deep callback when he points out that Ava’s old husband Bowman Crowder never saw his murder coming, but Bowman sure as hell wasn’t Boyd, and the episode makes no bones about closing with Boyd watching a sleeping Ava, his suspicions no doubt already ignited. After stranding Ava in prison for most of last season, Justified has already found a far superior role for her here, though her scenes don’t always quite work, as the script and Joelle Carter’s performance sometimes hit the melodrama of the moment harder than is necessary. Still, this too ought to carry Ava to the end of the series, assuming she is able to stay alive that long.

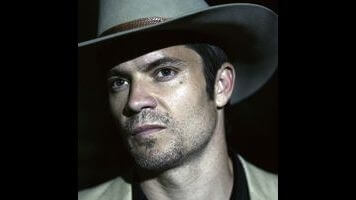

Raylan’s story, on the other hand, operates more at the scale of a vignette, perhaps even a one-liner. Raylan is more a presence than a character in this episode, on hand to dispense Justified’s usual quota of badass behavior. His capture of the corrupt federale and his shovel-based method of capturing a two-bit Harlan hoodlum represent moments of peak Justified; they represent the show emphatically reasserting its identity after a little too long spent ambling through the wilderness. While the opening scene with Winona and the baby—and, to a lesser extent, the closing scene with Art—suggests the broad outline of Raylan’s path this season, the rest of “Fate’s Right Hand” suggests Raylan still doesn’t really know what he wants out of any of this, if only because he is so consistently presented in terms of those around him. To Rachel and Vazquez, he is an instrument of what they can only hope is justice, with both strategically looking the other way as they send Raylan to do all the things he’s always done. To Ava and Dewey, he is the looming shadow of fate, there to threaten them with jail if they don’t cooperate. The anger is absolutely still there—one need only look at how he shakes down Ava after Boyd fools him and Tim—but beyond that, Raylan remains lost, doing what he does here at best because it’s his job and at worst because he just doesn’t know any other way. Perhaps that’s part of why he betrayed a sudden flash of nostalgia when discussing his family home. And perhaps that’s why he needs to have his climactic confrontation with Boyd sooner rather than later.