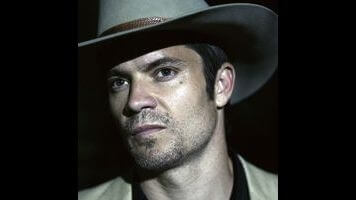

Justified: “The Kids Aren't All Right”

Unlike so many other protagonists of this era of prestige dramas,

Raylan Givens is no antihero. He’s a stubborn asshole, to be sure, and he has

what could be charitably described as an open-ended relationship with proper procedure. But even if his drive for justice is inextricably tangled up in his

anger and in his family’s criminal legacy, that doesn’t alter the fact that his

primary motivation is to uphold the law. His underlying motivations could

perhaps be considered selfish, but that’s only a fair assessment if one demands

that all law enforcers be driven solely by the very highest of ideals. He

frequently bends and very occasionally breaks the rules, but almost never in

the service of his own personal betterment. Raylan isn’t perfect, but he is a lawman.

That’s why his actions in last season’s finale “Ghosts” were so momentous. In

delivering Nicky Augustine to Sammy Tonin, Raylan crossed a line in a way he

never really had before. He indirectly organized a man’s murder for the very

best of reasons; indeed, one might wonder if Raylan would have taken so drastic

an action if Augustine had not made it so clear that his vengeful wrath included

not only Raylan but also Winona and the baby.

Raylan ended last season more compromised than ever before, yet I

wouldn’t necessarily have minded if the show had let him get away with it. He had

proved his heroic bona fides enough times and the murder of Augustine was so

clearly—to choose a word at random—justified that I was actually prepared to

view Raylan’s decision as a forgivable onetime lapse. Hell, in the context of

the show’s Western roots, Raylan’s decisive action might even be considered properly heroic, even if the modern-day authorities would surely disagree with that

assessment. Last week’s “A Murder Of Crowes” did not suggest any

fallout was imminent, but that all changes with tonight’s episode, as Art

starts digging into just why Sammy Tonin would have phoned Raylan shortly

before he was murdered. The fact that Art doesn’t immediately get angry with

Raylan or jump straight to an accusation could well be telling. After all, Art

knows from experience that it’s damn near impossible to reprimand Raylan

without learning something he really, really does not want to know. It’s early

days yet, but Justified likely wouldn’t start Art’s investigation

quite so softly if it didn’t intend it to be a slow build. Raylan made a deal

with the devil, and it looks like he will pay the price for choosing such a

singularly stupid devil.

It’s entirely appropriate that the proverbial noose begins to

tighten around Raylan in an episode that makes one of the show’s most powerful

arguments as to why this world needs like a lawman like Raylan Givens. After

ceding the spotlight in last week’s premiere, Raylan is the unquestioned star

of “The Kids Aren’t All Right,” as he is once again drawn into the troubled

life of Loretta Macready. There’s an old notion in fiction that to

save someone’s life is to take responsibility for it forever, and that’s as

good an explanation as any for the relationship between Raylan and Loretta. Despite her obvious manipulations and the almost galactic obnoxiousness of her

boyfriend, Raylan can’t help but sort out her messes.

Admittedly, Raylan would probably do what he does here for any

pair of wayward teens dumb enough to get mixed up with the Memphis marijuana

outfit—particularly when one teen’s social worker is as fetching as Amy Smart’s

Allison—but he likely wouldn’t bother with the lectures. Beneath all the

entirely understandable cynicism and exasperation, Raylan still believes

Loretta can be better than she is, or else she can learn enough pity to go easy

on the rest of the world. For her part, Loretta makes it clear that Raylan is so

fundamentally constant that she can maneuver him into doing whatever it is she

needs of him. That assessment doesn’t reflect all that well on either of them,

but at least Raylan is struggling toward something resembling improvement.

Again, that may just be to win over Allison, but Raylan has done far worse

things for far worse reasons.

Speaking of which, Raylan’s confrontation with the greatest beard

in television history—and I guess the murderous drug dealer behind it, but

let’s not lose focus—illustrates the precariousness of his current position,

morally speaking. As Rodney “Hot Rod” Dunham points out, the reputation

attached to Raylan’s surname precedes him; this isn’t the first time this weed

kingpin has been called out to a late-night meeting with a Givens, and so it’s

probably just a tad difficult for him to look at Raylan as an irreproachable

dispenser of justice. The marshal deflects the issue, as he’s an old expert at

ignoring Arlo’s legacy, but his already tenuous grip on the moral high ground

is shaken just that little bit more. Indeed, Raylan is rarely as direct with

his threats as he is here, plainly stating that he’s capable of killing the

majority of Dunham’s men—in part because of his own youthful experiences with Arlo’s criminal enterprises—and his badge makes it all legal. Raylan never learned to walk away because, unlike Arlo, he never actually has to.

Raylan’s statements aren’t corrupt, exactly, but they suggest a

dangerous precedent. Raylan generally does whatever he believes he needs to do,

and his overriding belief in the ideal of justice that the badge represents is

what allows for the occasional bending of the rules. The phrasing here

indicates Raylan is prepared to do what he has to and simply wave his badge

around afterward as ex post facto justification. Between this and “Ghosts,” Raylan appears to be at

his most corruptible when those he cares about most are in danger. That stated need

to protect “me and mine” is part of what drives men like his father into a life

of crime; Raylan lacks the greed for power and wealth that helped define Arlo,

but he seems to be having a harder time maintaining that heroic detachment

from his more primal impulses.

As for Harlan County’s actual outlaw, Boyd Crowder has

regained a great deal of composure after his own potentially disastrous

tactical blunder. It’s worth contrasting what led the two men to their

potentially fatal mistakes: Raylan allowed Nicky Augustine’s execution in order

to save his ex-wife’s life, whereas Boyd nearly beat Lee Paxton to death over

the honor of his future wife Ava. The motivations come from similar places, but

their manifestations reveal the fundamental differences in Raylan and Boyd’s

natures. When faced with the threat of imminent death for him and his loved

ones, Raylan remained rational enough to outwit the prideful mobster, but Boyd

could not control himself when faced with a mere insult—even allowing for

Boyd’s concern for Ava’s freedom, that’s still a useful illustration of why

Raylan and Boyd find themselves in such different circumstances.

That said, it never pays to underestimate the strategic mind of

Boyd Crowder, particularly when he has had a bit of time to collect himself. He

appears genuinely fascinated with Mara’s seemingly inexplicable refusal to

identify him as her husband’s assailant, a decision that earns the frankly

terrifying ire of Deputy Nick Mooney. Mara is likely to cost Boyd dearly, one

way or another, but Boyd likely appreciates the intellectual stimulation of

trying to work out just what her game is. As his world collapses around him, he

can use just such a distraction. As he discovers in the final scene, forces

unknown have declared total war against him and his criminal enterprise, and

the only recourse immediately available to him is to try to hide it all away. At

the end of both “A Murder Of Crowes” and “The Kids Aren’t All Right,” Boyd was

presented with seemingly insoluble problems. In the first case, he lost

control, while here he numbly maintains his composure. The problem for Boyd is

how little difference it seems to make. No matter how he responds, the world

seems to have it in for him.

Stray

observations:

- Wynn Duffy has his fair share of criminal talents, but he does

not appear to be the most charismatic of public speakers, at least as far as

the pushers of Harlan County are concerned. Perhaps he should have tried

engaging them with a little analysis of Marion Bartoli’s run to the title at last

year’s Wimbledon. - “Yeah, well, have a good one.” Timothy Olyphant is rarely

funnier than when he’s offhandedly dismissing some angry jackass. It’s a marvel

he doesn’t punch that punk Derek right then and there. - “Would you prefer that I

respond point by point or should I wait till the end?” This isn’t Hot

Rod Dunham’s first negotiation, people. Though, again, I’m almost positive that

the beard is really calling all the shots. - The Crowes only appear

briefly here, as Daryl Jr. drops in on an obviously terrified Dewey Crowe. Also,

it’s deeply weird to hear the world’s cuddliest neo-Nazi make an actual

reference to Adolf Hitler; it’s the rare instance where one has to at least

consider whether Dewey actually buys into the horrific, hateful philosophies

implied by his tattoos. That said, I’d be shocked if Dewey’s conception of

Hitler is connected to, well… anything.

He’s still probably too dumb to believe anything that stupid.