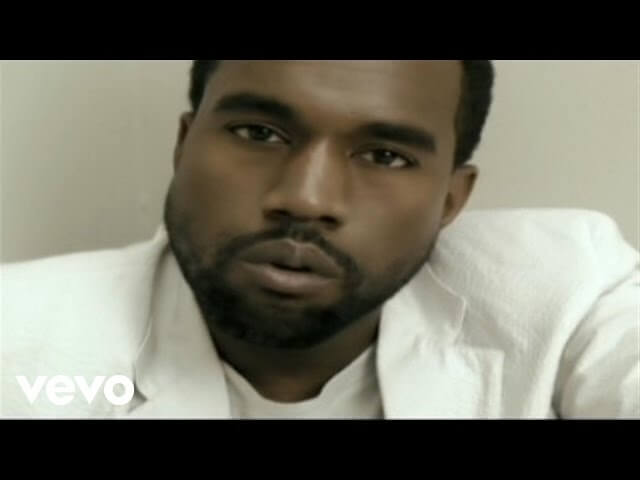

Kanye West’s 808s And Heartbreak

In We’re No. 1, A.V. Club music editor Steven Hyden examines an album that went to No. 1 on the Billboard charts to get to the heart of what it means to be “popular” in pop music, and how that concept has changed over the years. In this installment, he covers Kanye West’s 808s And Heartbreak, which went to No. 1 on Dec. 13, 2008, where it stayed for one week.

If ever there was a period in modern American history that deserved to be described in Dickensian terms, it was November 2008. If you voted for Barack Obama (or just appreciated the historical significance of our country electing a black president) it was the best of times, the age of wisdom, the epoch of belief, the season of light, and the spring of hope. But if you paid any attention to the financial news pages (or simply owned a house that was now worth a year’s pay less than what you paid for it) it also seemed like the worst of times, the age of foolishness, the epoch of incredulity, the season of darkness, and the winter of despair.

Whether it was the best of times or the worst of times might have depended on your point of view, but it was more likely that these states existed concurrently, with the former masking the latter, but never completely. It was a period when change promised deliverance from steep pitfalls that appeared to be widening and deepening all the time. But the desire—nay, the need—to believe that idealism was enough couldn’t really stave off the void that was opening up below.

Under no circumstances should Kanye West’s 808s And Heartbreak—released on Nov. 24, and the country’s top album for one week in December—be considered a political record. Its creator has never been all that selfless. West was an avowed supporter of fellow Chicagoan Obama, but he was on a flight to the MTV Europe Awards the night of the euphoric election-night celebration in his hometown. He was happy, but also on the move, well-practiced in the art of sidestepping voids. 808s was West’s escape hatch, and the album’s unusual emotional tone—distinguished by overwhelming feelings of self-pity expressed in chilly, remote fashion, using the shiniest trappings of contemporary pop in an utterly joyless manner—perfectly reflected the mood of a country saddled with mountains of possessions that were suddenly worthless, and a sense of panicky helplessness about what to do next.

A No. 1 record that seemed to alienate listeners as much as excite them, 808s And Heartbreak can lay legitimate claim to helping shape hip-hop in its wake. The current crop of moody, introspective MCs like Drake and Kid Cudi (who appeared on the record) seems inconceivable without it. The greatest testament to 808s’ influence is that the controversy it created now seems like a product of the specific place and time it came out of, even if it was only three years ago.

The most divisive aspect of 808s was West’s prominent use of Auto-Tune on most of the tracks, which allowed him to sing (or “sing”) as much as rap. That West was using Auto-Tune wasn’t unusual; he admitted in interviews promoting the album that he had used the pitch corrector on all of his records, along with pretty much every other contemporary recording artist. Getting upset about Auto-Tune is like getting upset about overdubs, or any of the other million ways that live sound is sculpted in the studio. It’s simply part of modern record-making, a process that’s presumed (or should be anyway) to be an act of construction, not in-the-moment being.

What bothered West’s critics was that he was going the T-Pain route, using Auto-Tune, in the words of critic Sasha Frere-Jones, as “the rare edit that calls attention to itself.” Used as it was intended, Auto-Tune is undetectable. But in the hands of T-Pain, it became the signature vocal effect in pop music—looking back, it’s maybe the most “late-’00s thing” about the late ’00s. Frere-Jones offers a handy tutorial on how this method of using Auto-Tune works:

Auto-Tune locates the pitch of a recorded vocal, and moves that recorded information to the nearest “correct” note in a scale, which is selected by the user. With the speed set to zero, unnaturally rapid corrections eliminate portamento, the musical term for the slide between two pitches. Portamento is a natural aspect of speaking and singing, central to making people sound like people … Processed at zero speed, Auto-Tune turns the lolling curves of the human voice into a zigzag of right-angled steps. These steps may represent “perfect” pitches, but when sung pitches alternate too quickly the result sounds unnatural, a fluttering that is described by some engineers as “the gerbil” and by others as “robotic.”

With T-Pain’s inhuman, Auto-Tuned croon appearing on seemingly every hit song in the latter half of the ’00s, the sound came to epitomize all that was ephemeral and empty about pop. It seemed to some like cheating, or a betrayal of truly talented singers now thrust on the same playing field as glorified shower-warblers. Even if these complaints missed the point—Auto-Tune vocal hooks were supposed to sound mechanical and larger-than-life, and were never passed off as “authentic” singing—Auto-Tune came to be thought of as the musical equivalent of steroids, and was similarly condemned in the media. Time magazine included Auto-Tune on its list of the 50 worst inventions (alongside abominations like the Pinto and Betamax), claiming that it can make “bad singers sound good and really bad singers sound like robots.” (Actually, it can make Al Green sound like a robot, too, but point taken.)

At the 2009 Grammys, Death Cab For Cutie showed up wearing light blue ribbons as a statement against so-called “Auto-Tune Abuse.” “A little use is okay,” Gibbard told MTV News, “but there is a difference between ‘use’ and ‘abuse.’” Added bassist Nick Harmer: “Musicians of tomorrow will never practice. They will never try to be good, because, yeah, you can do it just on the computer.” West’s mentor Jay-Z took perhaps the most public stand of all against the devil Auto-Tune, insisting that all traces of it be removed from his 2009 album The Blueprint 3 and releasing the strident “D.O.A. (Death Of Auto-Tune)” as the album’s first single.

West clearly didn’t share Jay-Z’s misgivings, telling MTV, “It’s just sonics.” For 808s—the title referring to the pioneering drum machine originally decried, then celebrated, for its inorganic sound—West set out to use the inescapable vocal effect in a deliberately non-pop way on an album expressly intended for the pop audience. “I wanted to use Auto-Tune to distance myself from that traditional rap sound,” he told The Telegraph. In a radio interview, he was even more emphatic. “If you were a little kid and went to the studio, you’d say, ‘Put the Auto-Tune on, give me some distortion, make it sound cooler.’ I wanted it to sound cool.”

With typical modesty, West claimed that 808s heralded a new musical genre: pop art, a “new” term only to those not familiar with Andy Warhol, but conceptually interesting nonetheless. (West conceded that Pink Floyd also belonged under the “pop art” banner.) The “pop” part of 808s was represented by, of course, Auto-Tune and the emphasis on melody and the tone of the beats rather than propulsive hip-hop rhythms; the “art” (or “heartbreak”) came from West’s own life, specifically the recent break-up of his engagement to Alexis Phifer and the 2007 death of his mother Donda West from complications during elective plastic surgery. Both losses could be attributed (in West’s mind, at least) to his success; when women leave Kanye, it’s still all about Kanye. It was the same dueling fit of megalomania and self-recrimination that had been at the heart of his persona since his 2004 debut, The College Dropout, only now exacerbated by personal tragedy.

“Pop is such a clear lane, for people to do bullshit music and it still works,” West said. “This has 72 bars of real life lyrics that’s from my life, that I wrote. Now compete with that.” Actually, West was now setting his competitive sights beyond his contemporaries. “I now want to be grouped among those musicians you see in those old black-and-white photos—the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles,” West told The Telegraph. “And I’m not going to get there by doing just another rap album full of samples.”

An unflattering, warts-and-all depiction of male jealousy, insecurity, and romantic bitterness that occasionally veers uncomfortably toward misogyny, 808s And Heartbreak didn’t so much recall the Stones, Hendrix, or The Beatles as a similarly talented and prolific singer-songwriter known for exhibiting a mean streak toward women. In form if not so much sound, 808s And Heartbreak was Kanye West’s Elvis Costello record.

Everything you could ever want to know (or wish you could forget) about men, you can learn from listening to Elvis Costello’s first two albums, 1977’s My Aim Is True and 1978’s This Year’s Model. Taken together, they offer a devastating portrait of the weakness and anger, lust and resentment, adoration and confusion that informs how many young males view women. What raises these albums to the highest levels of artistry—and makes them albums about misogyny rather than nasty byproducts of it—is how Costello doesn’t celebrate these feelings, he exposes and eviscerates them. He does it with typical subtly; each twist of the knife comes with a turn of phrase here and a vocal tic there, digging deeper in the flesh.

On “Alison,” it comes via a single brilliantly rendered line: “I heard you let that little friend of mine, take off your party dress.” It’s all there: the passive-aggressive fury, the barely concealed hurt, the “is she really going out with him?” inferiority complex kicking in hard. Later, Costello sings, “my aim is true” over and over, sweetly, seemingly in reverie. Then you remember the part where he wishes he could stop Alison from saying the silly things she says. “I think somebody better put out the big light,” he seethes. Elvis might as well be a sniper singing a final lullaby, serenading Alison while staring her down through a riflescope.

The Elvis Costello of My Aim Is True and This Year’s Model is funny and whip-smart; he’s also a bit of monster, and I don’t think I’m mistaken to have that impression. When I was an alienated teenage boy, I related intensely to late-’70s Elvis Costello because I wanted to believe that I shared his intelligence, but really I only connected with his shortcomings. Costello projected an “angry nerd” image that railed against everyone and everything that didn’t recognize his inherent superiority, but his songs cataloged the fissures in his personality. He was pissed that girls didn’t look at him, but his hostility was ultimately directed inward. That boomeranging bitterness—sent venomously toward women but always coming back tenfold—is also all over 808s And Heartbreak.

This Year’s Model opens with “No Action,” a song that likens obsessively calling a girl you like who doesn’t like you back with pent-up sexual frustration. 808s begins with West on the other end of a phone call. “Why would she make calls out the blue?” he says at the start of “Say You Will” over a listless beat and a mournful chorus moaning in the distant background. You can feel Costello’s nervous energy immediately in the pounding of Pete Thomas’ drums; West sounds dead, or at least in the midst of a narcotic fog.

The threat of violence is implicit in both songs. West is less lively, and yet he comes on stronger in this regard: “When I grab your neck, I touch your soul,” he says. (Costello, always the clever boy, merely says, “Every time I phone you, I just want to put you down.”) And yet neither of these guys possesses any kind of power; it’s the very lack of power in the face of their fruitless infatuation that’s got them so bunched up. West is humiliated to “admit that I still fantasize about you,” which is likely the very thing in Costello’s head that is hurting his mind.

I realize that I might be giving these guys too much credit because I happen to like their music. Elvis and Kanye might not be as self-aware as I think they are. It’s possible they were merely women-hating pricks when they made these records. Maybe when Costello sang, “You want her broken with her mouth wide open” on “This Year’s Girl,” he was just being honest (and unapologetically so) and didn’t give a damn how he would be perceived. And West really thought people would side with him at the end of “Robocop,” when he petulantly sings, “You spoiled little L.A. girl / You just an L.A. girl.”

But… I don’t think that’s true. (Certainly not on “This Year’s Girl,” which has a glint of empathy buried in its cold, pinched heart.) When Kanye West puts the Auto-Tune on his pitch-challenged vocals, he doesn’t sound popular, perfect, or true. He sounds like a guy who’s lost touch with an important part of himself, and cannot (or will not) find the wherewithal to recover it. Auto-Tune doesn’t make 808s And Heartbreak sound cooler; it makes it sound colder, like a tomb enclosing a man with his stickiest, shittiest thoughts that he can’t express with his usual eloquence.

If Kanye West has proven anything over the past several years, it’s that he can make swaggering crowd-pleasing jams that will make you accept whatever self-aggrandizing gibberish comes out of his mouth. He does no such thing on 808s. Here, West makes plain the lies of what he’s saying by how he says it—using a tool that has covered up a million little vocal mistakes, and, on this record at least, exposed a man’s tenuous grasp on his own humanity.

Coming up: REO Speedwagon’s Hi Infidelity