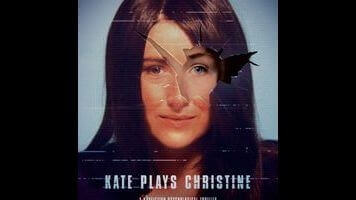

Kate Plays Christine in a tricky film about a famous suicide

Some movies blur the lines separating fiction and nonfiction, performers and characters. Kate Plays Christine makes those lines the whole show. The film is directed by Robert Greene, who shoots relentlessly self-devouring doc-like-things when not working as an editor for Alex Ross Perry, among other collaborators. His last project explored the nature of performance through a retired B-lister’s attempted comeback, all while heavily hinting that not everything happening on screen was strictly real. But Actress, as the tricky thing was called, looks downright straightforward compared to Kate Plays Christine, which casts its own methods and intentions under constant suspicion. To just call it a documentary would be more than misleading.

The film’s ostensible subject is Christine Chubbuck, a Florida news reporter who shot and killed herself during a live broadcast in 1974, in what’s considered the first televised suicide. (The incident also provided the loose inspiration for Network.) Greene comes at this stranger-than-fiction material through indie starlet Kate Lyn Sheil (House Of Cards, Sun Don’t Shine), who’s researching Chubbuck’s life in preparation to portray her in a dramatization. This allows Kate Plays Christine to function, right from the start, on two different levels: as both a biographical overview of the Christine Chubbuck story and as a portrait of Sheil’s process, which involves traveling down to Sarasota to talk with surviving colleagues, hunting down footage of Chubbuck (the tape of her suicide was thought until very recently to be lost), and meeting with the wig, makeup, and costume artists that will help her get into character.

Sheil, who’s brought more than a few troubled souls to the screen, doesn’t look or sound much like Chubbuck. (Rebecca Hall, who appears in Antonio Campos’ upcoming biopic Christine, bears a much closer resemblance.) Nevertheless, the actress confesses a growing identification with her “character,” another woman who made a living subjecting herself to the camera’s (and the industry’s) harsh gaze. Poring over transcripts of the infamous incident, Sheil begins to doubt any effort to psychologically explain Chubbuck’s actions. And is it flat-out exploitative to put the woman under a new microscope? As one interview subject muses aloud, no one would make a movie about this predominately ordinary life were it not for the very unordinary way it ended.

That’s enough conflict for one documentary, but Kate Plays Christine has more on its mind; every time you think you’ve got a grip on it, it plunges deeper into its own house of mirrors. Greene, it’s eventually revealed, is also the director of the biopic Sheil is supposedly headlining, and the excerpts he includes look so movie-of-the-week tacky—so deliberately amateurish—that they make it hard to take the film’s basic premise at face value. Is Sheil really preparing for a role, or is she just starring in a movie about preparing to star in a movie? The verité, just-hanging-with-Kate portions of Kate Plays Christine become gradually less convincing, too, until they vaguely recall one of Sheil’s stylized psychological thrillers. Beyond the increasingly porous barrier separating Kate from Christine, the film hits on a larger point, one supported by twin scenes of the actress buying a gun (first as herself, then in character): Documentaries are as phony, in what they choose to show us and how their subjects behave while we’re watching, as their entirely fictional counterparts.

There’s an emotional dimension to Kate Plays Christine—an empathy linking an actor to the human headline she’s dressing up as—that’s nearly abstracted into oblivion by the film’s neurotic self-examination. The climax, for one, is too clever by half: Ready to shoot the big reenactment Greene has been teasing since his opening shot, Sheil theatrically, sanctimoniously breaks the fourth wall to summarize the film’s moral position on itself. After two hours of skillfully evading the question of whether we’re seeing the “real” Sheil or some naturalistic mirage of the same, the actress badly shows her hand. Then again, this is the type of transparently meta movie that deflects such criticisms by its very nature. Every design flaw, calling attention to the artificiality of the project, could be a feature—another way for Greene to make the point that behavior is performance, at least when there’s a camera around to capture it. All the footage in the world won’t show us the real Kate. The real Christine either.