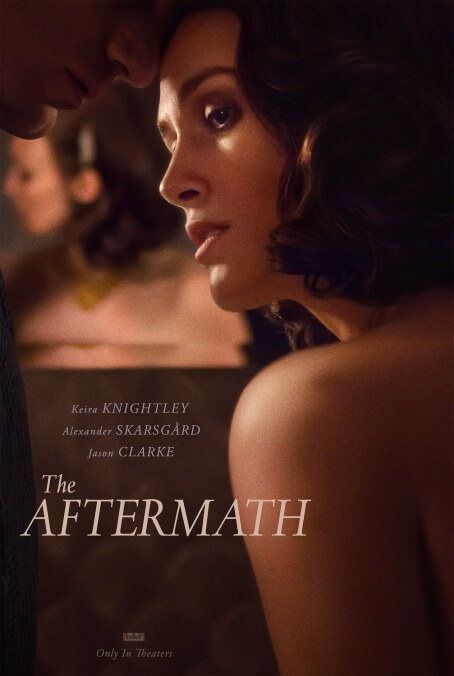

Its setting, however, remains unusually rich. The period during which Germany was divided by the Allies into four zones, each controlled by a different country, has inspired some classic movies, including Roberto Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero, Lars von Trier’s Zentropa and, more recently, Christian Petzold’s Phoenix. (Soderbergh, too, tried his hand, though The Good German is one of his less-acclaimed films.) But it’s rare to see the occupation itself depicted as more than a backdrop. The Aftermath’s drama derives entirely from the uneasy living arrangement agreed upon by a British colonel, Lewis Morgan (Jason Clarke, who’s Australian and sounds more American than English here), and his wife, Rachael (Keira Knightley). The couple have requisitioned a beautiful house in Hamburg, owned by widowed architect Stephen Lubert (Alexander Skarsgård, who’s Swedish and sounds indeterminately European when speaking English), and have the authority to remove Lubert and his teenage daughter, Freda (Flora Thiemann), who would then go live in, essentially, a refugee camp. Instead, Lewis magnanimously invites the Germans to stay, albeit up in the attic, and Rachael reluctantly goes along with the plan, despite her hatred for the entire country.

She has reason to be angry, as it turns out. The Aftermath opens with a gorgeously forbidding overhead shot of bombs exploding in darkness, and it’s quickly revealed that Rachael and Lewis had a son who was killed a few years earlier, during a German bombing raid. They’re both still very much in mourning—Rachael openly, Lewis in the time-honored, deeply repressed fashion of men in general and British military men of the mid-20th century in particular. Lubert and his daughter, likewise, are devastated by loss, having been stripped not just of their wife and mother, respectively, but also of their national autonomy. The movie works to the extent that it roots Rachael and Stephen’s affair in their shared grief, suggesting that they don’t love or even desire each other so much as they just long for an escape from the numbing pain. This aspect grows stronger as The Aftermath goes along, culminating in a resolution that’s deeply satisfying.

Getting there is kind of a drag, though. The film’s director, James Kent, previously made Testament Of Youth, another wartime adaptation (of a WWI memoir, in that case), and has done a lot of work for British TV; his touch tends to be overly emphatic, taking the most direct (and thus least effective) route to a character’s feelings. Since Rachael and Stephen are destined to do the dirty, their initial relationship isn’t just chilly but downright hostile—Rachael refuses to shake Stephen’s hand when they first meet, and somehow can’t intuit, after living in his house with him for several days, that the wife he speaks of must have died in the war. (“Oh, I guess she’s around here somewhere?”) The subsequent love triangle never transcends generic signifiers of passion and neglect: Knightley quivers expertly, Clarke plays it gruff and oblivious (until Lewis gets the bad news, at which point his performance shifts into a much richer gear), and Skarsgård mostly stands around looking very handsome in cable-knit sweaters, failing to sell such clichéd moments as Stephen suddenly kissing Rachael in the midst of a heated argument. Also, the movie keeps digressing into a rickety subplot involving Freda’s romance with a kid who remains devoted to the Third Reich; this presumably has more import in the novel, but comes across as padding onscreen. Ultimately, there’s not enough here beyond that simple eight-word synopsis. It could even be reduced to half as many words: They’re sad; they bone.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.