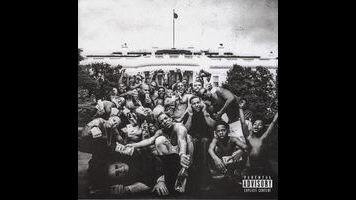

Kendrick Lamar resists connecting the dots on To Pimp A Butterfly

No accomplishment in hip-hop is rarer or more celebrated than the classic debut, so the rap world was eager to welcome Kendrick Lamar’s breakthrough Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City as one in 2012. Never mind that it wasn’t actually Lamar’s first album: Good Kid announced the arrival of a major talent, and like every mythologized rap debut, it seemed almost presciently aware of its own importance. Lamar even subtitled the album “A Short Film By Kendrick Lamar,” a needlessly pretentious billing that telegraphed his cinematic vision for the project. He brought a screenwriter’s sense of order to Good Kid’s day-in-the-life narrative about coming of age in Compton. Even its detours were tightly plotted. The trade-off for that meticulous structure, however, was that it fed Lamar’s tendency to over-explain himself. He highlighted every theme in yellow, repeating and underscoring every major point, often with redundant skits and interludes. The album played like a Cliffs Notes version of itself.

On Lamar’s longer, denser, and even richer follow-up To Pimp A Butterfly, he stops holding the listener’s hand. As on Good Kid, he’s consumed by hot-button issues—racial injustice, skin tone, addiction, broken homes, sexual politics, the limits of faith, and the legacy of slavery among them—but this time he refuses to connect his own dots. Where Good Kid was a linear story, To Pimp A Butterfly is an 80-minute pileup of loose ends, unfinished thoughts, and contradictions. Lamar will hint at a conclusion, then refute it; point fingers, then redirect them. And sometimes, as if maddened by the impossibility of making all these misshapen puzzle pieces fit together, he turns his anger on himself. He screams his parting verses on “U” into a hotel mirror, berating himself for abandoning his old neighborhood, including a fallen friend he never got around to visiting in the hospital. On the raging “The Blacker The Berry,” he continually calls himself out as a hypocrite. At first, he wears the word with some pride, but by the song’s end it’s a damning slur, snarled with disdain.

Befitting Lamar’s thematic sprawl, the music on To Pimp A Butterfly is similarly wide-ranging, crowded with swollen funk grooves and scribbled jazz horns, and almost completely uninterested in anything resembling a radio single. There’s plenty of recent precedent for albums this virtuosic and unbound, but it comes not from rap but rather neo-soul, where artists like Erykah Badu, Bilal, and D’Angelo have painted on ever-expanding canvases. Bilal in particular serves as a model for Butterfly’s warm, studio-session feel. He flanks Lamar periodically, as part of a rotating chorus of credentialed soul singers including James Fauntleroy, SZA, Anna Wise, and Lalah Hathaway. Jazz pianist Robert Glasper, another player with deep ties to the neo-soul scene, lays his dazzling key-work all over the “For Free” interlude, and even the tracks built from samples feel as if they were recorded live.

There’s a moment at the end of To Pimp A Butterfly where Lamar teases a clean takeaway from this impressionistic mishmash of stray thoughts and new and old black music styles. “Mortal Man” culminates in a lengthy, imagined conversation with Tupac Shakur, pieced together from a 1994 radio interview with the late rapper. Lamar hits it off with his idol. They exchange their views on society and art, laughing in agreement. Then Lamar closes with one last question, positing a long, plausible-enough theory that would seem to tie the album’s primary themes together into one poetic metaphor about butterflies and caterpillars. “What’s your perspective on that?” he asks Shakur, eager for affirmation. But instead he receives only silence, as the album ends abruptly. Even in its final moments, To Pimp A Butterfly refuses easy answers.