Kenny wasn’t like the other kids: An oral history of MTV’s Remote Control

A raucously sarcastic take on the game show genre, Remote Control burst onto MTV in 1987. Part of the cable channel’s first wave of non-video-centric shows, Remote Control skewered vintage pop culture with its “mom’s basement” style set, cigarette smoking commentators, and questions about everything from physics to The Brady Bunch—or a combination thereof. Contestants slouched in brightly colored Barcaloungers, were pelted with snacks between questions, and got pulled backward through breakaway walls upon elimination. Host Ken Ober (who died in 2009) held court with an everyman sneer alongside announcer Colin Quinn, while comedians like Adam Sandler and Denis Leary popped in to ask questions in guises such as “Stud Boy” or legendary animal trainer Gunther Gebel-Williams. It made both no sense and total sense.

It was the perfect MTV show for its era; unfortunately, like so many other shows from the network’s first decade or so, it came and went relatively quickly before sinking into pre-internet obscurity. If Remote Control is remembered at all, it’s as part of the gonzo legend of ’80s MTV, or as the show that first humored Sandler. But its legacy stretches into shows like Where In The World Is Carmen Sandiego and The Real World, and its production team would not only ascend to the leadership ranks at MTV, but also at Comedy Central and Freeform, where it would shape programs as varied as All That, Smallville, and The Daily Show.

Many of the people who made the show call it the best job they ever had. In recent months, The A.V. Club has spoken with 21 of them—producers, writers, cast members, and contestants alike. So pull up a La-Z-Boy and enjoy this oral history of Remote Control.

Interview material has been edited and condensed for clarity. All credits refer to Remote Control unless otherwise noted.

In 1986, five years into its on-air existence, MTV was humming along, flush in groundbreaking music video content and a fervent base of 18-to-24-year-old fans. Still, its executives were facing a problem: Music video programming wasn’t holding viewers for long periods of time. If someone at home didn’t like the song that was playing, they’d switch over to another channel and watch something else instead. Thus, the idea of expanding into more traditional programming was born.

Doug Herzog, executive producer: I got [to MTV] in 1984. MTV launched in ’81 with music videos. By ’84, it had reached its apex in that area. 1984 was the year of Michael Jackson’s Victory Tour, Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA,” Prince’s “Purple Rain,” and Madonna. It was like the Mount Rushmore of music video. MTV was growing wildly and rapidly, and we were in enough homes where ratings actually started to mean something to advertisers.

Not surprisingly, the guys who were running MTV like [then-CEO] Bob Pittman discovered that, if we were going to change our programming every three or four minutes, that’s not really going to work that great for engagement, which is something we’re still talking about to this day. We needed to build longer engagement to keep people around longer so that they didn’t switch the channel. [Pittman] brought us into a conference room and said, “We’re going to try doing half-hour programs.” We had done shows before, but they’re all basically shows with videos. Top 20 Countdown… everything is built around videos. He said, “We’re going to do three shows. We’re going to do a news show, we’re going to do a dance show, and we’re going to do a game show.”

One of the reasons they landed on the game show was [sister channel] Nickelodeon, which was also in its infancy, was doing game shows. They had done Double Dare, which was a big hit for them. So the network understood you could make 65 [episodes] of them pretty cheaply. Game shows were efficient ways to get things done.

[pm_embed_youtube id=’PLCIHMEGqcpGZhh4XnB0bLqrTgUR313Y2h’ type=’playlist’]Dana Calderwood, director: If you look at the history of cable, you will find that, with almost every new cable network, at some point one of their early shows is a game show, and it’s all about money. You can mass-produce them. You could do five to eight in a day. The cost per episode is low and all the games are set up so they could be done as an assembly line, basically. What that meant is that if [MTV is] going to roll the dice and produce its own programming, they’re going to say, “Let’s go with the cheapest thing possible.”

Herzog: The news team went to work on the news show. A separate team went to work on what became Club MTV, and myself and Joe Davola and Michael Dugan went off to do Remote Control, or the game show.

It was very controversial, too. To this day I run into people who go, “MTV doesn’t play any music,” but I go, “MTV hasn’t played music for 30 years. You’re not even old enough to remember when MTV played music.” They still complain about that.

I was a TV guy because I had actually worked for a couple of years in TV, but most of the brass and the higher ranking people at MTV in those days were radio people, record company people, promotion people, or live event and concert people. For a lot of people, it was all about the music. So this was highly controversial, both internally and externally.

Herzog, Davola, and Dugan assembled a small brainstorming group from within MTV, then promptly sequestered that group inside a Manhattan Hilton.

Sue Flinker, Senior Writer, MTV Editorial, and member of the brainstorming group: One great thing about the brainstorming session is that no one had game show experience. If you think about what TV is today, if you go for a job interview, if you don’t have Bravo experience, you’re not getting on a Bravo show. The problem with that is that it makes all those shows the same because they all bring the same experience that they’ve brought from show to show.

At MTV, we were genre jumping. We were going from doing a documentary on groupies to the next day writing a comic promo and the next day doing the MTV [Top 20] Video Countdown. We had such a fresh perspective. Nobody forced us to look at old models. We could just do whatever we wanted. That’s the one thing about MTV: You could never go too far.

Herzog: The basic idea for the show was created in that room on that day.

Flinker: One of the really important things to understand when you think about the genesis of Remote Control is that MTV had been doing these iconoclastic twists on formats for a while. [The channel was] taking the radio contest and amping that up. We did Paint The Mother Pink with John Cougar Mellencamp—the radio would just give you tickets or a backstage pass to see an artist, but we’re giving you a house, and John Mellencamp is your neighbor. Think about the MTV VMAs, and how that became must-watch TV because there were so many out there, crazy things going on. You couldn’t not see that show. In 1986, even, a group of people pushed to get a Monkees 20th anniversary weekend, and that did so amazingly well that they ended up having the Monkees do other programming. They did a Christmas video.

So in a way, we were priming the pump for more content that fit within the pop culture arena, not just music. All of that stuff seeded the idea for expanding content. When they came to us and said, “MTV wants to do a game show,” we said, “Well, that totally fits.”

Ultimately, the team in the room landed on Remote Control, a game show with questions about and adjacent to pop culture. At the time, cable was still relatively new, meaning most of MTV’s audience had grown up watching only a few television channels and a limited number of shows. Everyone in that room—and, they wagered, at home—had the same TV touchstones, from The Brady Bunch to The Facts Of Life, Hogan’s Heroes to The Price Is Right. If they quizzed contestants on those topics rather than on whatever A-Ha video was in heavy rotation at the time, the show could be brilliantly askew and weirdly unique. It could be Remote Control.

Herzog: Everybody loves TV. We all talk about TV. We love trivia.

Joe Davola, co-creator: It would be a lot more difficult to do the show today because you don’t have people who are all watching the same thing except for every once in a while. There are too many options.

We were able to span a couple of generations because we watched the same shows while we were growing up. Everybody grew up on the primary channels wherever they lived, plus the syndicated channels. Brady Bunch, Green Acres, all those shows are on a loop, so they were going to come across your screen at some point. Every afternoon when you get home from school, you’re watching three, four shows and they’re all things you’ve seen before. That’s when you’re really picking up the minutiae, and that’s why we can go really deep on some of these questions.

The creators decided that the Remote Control board would be based around the idea of individual television channels, with contestants choosing categories blindly from an oversized TV set. “Every subject was a channel, which was ahead of where cable TV was at that point. This was 1986 or 1987. There was no cooking channel and there was no Travel Channel and there was no dog channel,” remembers Herzog. Channels in the first season skewed fairly straightforward and included categories about Andy Griffith, “Cop Shows,” and The Odd Couple.

Another idea to come out of the Hilton brainstorming session was how the show would deal with eliminated contestants: They would be forced “off the air,” which, in the first season, meant their chairs were pulled back through the set wall behind them, making a hole that was then covered by a curtain. In subsequent seasons, chairs would flip backwards or do 180-degree spins. This became one of Remote Control’s most memorable—and hilariously effective—visuals.

Flinker: I remember thinking to myself, “It would be pretty lame if after two or three rounds for the [trailing] contestant, let’s say, to just get some parting gifts. We have to do something that makes people go ‘WTF.’ You can’t just politely say goodbye. You’ve got to eject them off the stage.” So, that’s where yanking them off their Barcalounger or going backwards behind the scenery came from.

Byron Taylor, set designer (season 1): The Barcalounger knockoff Naugahyde recliners were actually kind of hard to find in Manhattan. We had to go all the way down to the Lower East Side to some used furniture places to find three that were vaguely the same. And then they were all brown, so we wound up spray-painting them, which was kind of strange.

[Losing contestants were eliminated by] stagehands pulling each Barcalounger. Each one had a stick at the back of it that they pulled and then it went through the wall, that sort of thing.

Flinker: What was very cool is that the team who worked on Remote Control subsequently kept amping up and evolving that concept, making it more insane, more intense, and getting the studio audience involved in singing “Na na na na, na na na na, hey hey, goodbye” You take what you have and keep amping it up to the logical conclusion of craziness.

Marc Weissman, contestant: I got swept up in the chair. You’re up there for the rest of the [segment].

They made us wear L.A. Gear sneakers—that was a big brand at the time—and you can actually see my feet sticking up over the set. They had a TV that was upside down so I could actually still watch the show. Eventually, during the next commercial break, two huge guys just came over and lifted me out.

Also developed around that time was the show’s final round, during which the winning contestant would be strapped to a Craftmatic Adjustable Bed in front of a wall of TVs playing nine music videos simultaneously . They’d be charged with naming all nine artists in 30 seconds, and for each one they got right, they got a progressively better prize.

Davola: We had beat out the show, but we really didn’t think we had figured out the end game. Susan said, “What about a cacophony where [all the TVs] were on at the same time [and you’ve got to shut] them off. But we didn’t have the luxury to build [a rig at the time], so I pulled every TV set [at MTV] into a hallway and we put videos in all of them, and people started shutting them off one at a time. We figured out that that’s the way the game would work.

Michael Shore, MTV News, member of the brainstorming team: The one idea that I came up with was the Craftmatic, which was the last act of the show, the grand prize round. I worked for a paper downtown called the Soho Weekly News, which was a Village Voice-type alternative weekly. I used to cover the late night TV scene, if you can call it that. I would be out at nightclubs [covering] bands like Talking Heads or The Ramones or Blondie, and then everybody would say, “Let’s go home and catch Mary Tyler Moore,” which was re-running at 2 in the morning on NBC or something. That became a cult thing, so I started covering late night TV.

Anyway, everybody knew these crazy, silly ads that felt like the kind of products you’d only see advertised on cheap commercials on TV. [One of those products] was the Craftmatic bed, which was this bed that you could adjust up and down. So my contribution [to the brainstorm] was “How about if we have somebody sitting on a Craftmatic bed…” The idea of the final round was an outgrowth of the idea of lying in your bed when you’re ready to pass out and you might fall asleep with the TV on. This is the generation that grew up falling asleep with the TV on. It becomes a miasma of TV and you can’t figure out what you dreamed and what’s real. It’s all floating around in your head.

Jonathan Ezor, contestant: When you watched it on TV, they were zooming in on the screens [during the final round]. But [the bed] was quite a ways back from very small screens. [As a contestant] you’re looking at nine screens all at once from about 10 feet away. If I remember correctly, I think all the sound was playing too, not loud, but it was all one big mishmash. And you had to go in order or pass.

Rick Rosner, fact checker and writer: If you beat the wall, you [sometimes] won a Suzuki Samurai, which was this early compact SUV that had a high center of gravity, so it tended to flip over.

Because no one involved with Remote Control had worked on or created a game show before, the channel sought out veterans of the genre, including expert Howard Blumenthal and Double Dare’s Dana Calderwood, who were brought in to advise the MTV team on how to synthesize their zany ideas into an entertaining but fair and reproducible product.

Howard Blumenthal, game show consultant: They knew what they were doing, but the trick was to pull it all together as a show. You need the rigor of doing run-throughs every day and tweaking one little thing and testing [something] in five different ways and being very careful about the way we tied it to the brand.

Lauren Corrao, producer: There was a delicate balance of trying to figure out what that show was between how much comedy versus how much game, because it actually had to work as a game show. [Blumenthal came] as we got closer to putting it on the air just to make sure that we were following all the rules of play. He taught us how important the game was going to be to viewers and how you can’t take that for granted.

[Remote Control] was such a parody of so many different things that it was always meant to be a comedy, and so we knew absolutely we had to get that tone right. But we also knew absolutely that you had to be able to play along, that people would actually care if it was fair or not. In the beginning, we ran through some shows where it would be completely in the host’s control to take points away from people. They do that on a lot of British game shows and they get away with it. But in the U.S., I remember learning through Howard that it actually mattered to the viewers who was winning and who was losing and whether or not the game seemed fair to them.

Rosner: Game shows still were very constrained in their wackiness. There was still some propriety that was left over from the quiz show scandals in the late ’50s. So there was still a lot of, on game shows, “I guess we’re still in this box.” [Remote Control] was just whatever the fuck we wanted to do, [but Blumenthal] was still there [to say,] “These questions are fair. We’ve got to make sure this person rings in first and they get it.“

Calderwood: [I think the Remote Control team thought,] “If Nickelodeon can do a game show for kids, we can do whatever we want. It’ll be so cool because we don’t have any of those restrictions.” Everybody was young enough at the time that they probably didn’t care too much about corporate parents. There wasn’t as much overview from a corporate entity as there certainly is now. Everything now would have to go through a million levels of executives and committees.

Once the show’s framework was in place, it was time for casting. Herzog, Davola, and Dugan already had some people in mind from their time at Emerson College in Boston.

Denis Leary, cast member: When I was at Emerson, it was hard to get stage time when you were an underclassman, so we started this comedy theater group called the Emerson Comedy Workshop. The initial group of people included myself, Eddie Brill, Mario Cantone, [MadTV producer and writer] Lauren Dombrowski, and [Leary’s fellow Remote Control cast member] John Ten Eyck, who was a musician and an acting student. There were a lot of music students and film students that were tied in because we did three live shows a year, all original stuff. [Group member] Steven Wright was too shy to go on stage, but he was writing with [Remote Control writer] Mike Armstrong. Doug Herzog became a big fan of our shows.

So right after we graduated, Steve Wright went on stage at a stand-up club in Boston, which is how myself and then Mario Cantone started doing stand up. Then we started going down to New York because a bunch of our friends who were graduating, including Doug [Herzog], had gone down there. That’s how I met Colin [Quinn]. I brought Colin up to Boston to start making some money at gigs up there. Then Steven hits it big on The Tonight Show. Steven then runs into Doug some place in L.A. and Doug says, “I’m going to start working at MTV.” So that’s where it all started. And then Armstrong said he was getting hired with a couple of guys to work on an idea for a game show.

[Remote Control host] Kenny Ober went to UMass while we were at Emerson. He did a double act with a guy named Peter Tolan. They graduate. Peter goes to Minnesota and then to California, and starts working on television. Kenny Ober was hanging around the Boston comedy scene, so I already knew Kenny. He kept saying, “You got to meet Peter Tolan,” who later on I did Rescue Me and The Job with. So all of this goes back to Emerson. Really, that’s how it all started.

Colin Quinn, announcer: Joe Davola came and saw me do comedy when they were doing the show. I thought they were hiring me for my comedic wit, but really it was because I had a crazy gravelly voice and they thought it would be funny if I was the announcer.

Herzog: [Quinn] has that particular way that he performs where he swallows his words and he’s got the gruff voice and he talks too fast. In my 1986 head, I was thinking about [casting] more of a traditional big man type. I remember kind of pushing back on him [being cast] in the beginning and Joe was like, “No, he’s really funny. It’s really different. This is the guy. We should do this.”

Quinn: I almost got fired the first week because I had such a shit attitude. They made me read the commercials, so they’d say “Here, read Mitsubishi,” and I was like [With no affect.] “Mitsubishi Montero.” This is in the pilot. I’m reading prize copy, but with a bad attitude, just like, “How dare you make me do this? I’m a comedian. I’m not going to be a shill for your stupid product.” I could not have had more contempt in my voice. I almost got fired because a lot of [ad execs] were like, “Who is this guy? What a shitty attitude.” God forbid I change. I would read the prize copy so sarcastically.

For whatever reason, though, that became popular. Kids like nothing better than thinking somebody is saying, “Hey, fuck you.” [MTV was] getting complaints from the companies about how I was making the products look bad, but [kids loved that] I was insulting their copy because I thought I was above reading the commercials.

I despised the whole thing. So, like, for example, Chrysalis Records, right? I was calling it “Cry-Salus” Records. I didn’t know that that was wrong, but then when they told me to change, I wouldn’t change it. I was just being a prick, but it was also because I thought I was too good to be doing it. And for some reason, that worked.

The creators also tested a whole slew of potential hosts, including comedian Kevin Meaney, offbeat magician The Amazing Johnathan, and eventual Yo! MTV Raps creator and film director Ted Demme.

Herzog: Ben Stiller auditioned, if I’m not mistaken. As I remember it, we were kind of close to hiring him, and then he got a role on Broadway in a show.

Davola: His agent didn’t want him to do it. I think we also auditioned Tom Kenny.

You know who we brought in to be a writer or the show, or who I met with? Larry David. We had a meeting at his agency. He had just come off Fridays, the show that was a competitor to Saturday Night Live. He was kicking around New York and his agent set up a meeting with us. We talked to him about the show, and he was like, “I like the idea,” but basically said his career was way beyond writing on the show. Not in a snooty way, but he was right. The guy’s a genius.

Herzog: We auditioned [Partridge Family star] Danny Bonaduce, because we thought that was a kitschy concept.

Davola: I drew the short straw and flew out to L.A. one night on the red eye. I went to this office to interview and audition hosts, and Danny Bonaduce was one of the guys. I flew home and I literally was struggling, going, “Danny Bonaduce would be great for the press. He could get people to watch the show.” And he was funny. He did a good job, actually.

Danny Bonaduce, actor and radio personality: I did feel good about [the audition]. But that was a fairly rough time in my life, so any kind of job at all would have been great. Game show host would have been spectacular. That would have changed my life back then. I’m not even sure I had a house or an apartment or an address back then. The idea of becoming a not just a game show host, but a game show host for five or six seasons? That would be a big deal. The funny thing is that, in the long run, it would have cost me money, but back then it would have put food on the table, and I cannot tell you how important that was.

Herzog: [When Ken Ober] came in, it was natural. He was incredibly quick-witted. He was super smart, super funny. He was just able to step in. Hosting a game show and hosting anything on TV, not anyone can do it. It certainly looks a lot easier than it is. And Kenny was just a natural.

Davola: Ultimately, I remember [MTV Vice President] Lee Masters said to me, “Well, which person was better?” And I said, “It’s Ken Ober.” So he said, “Forget about the press with Danny Bonaduce,” and we went with Ken at the end of the day and it was the best move we ever made. I don’t think it would have been the show it was with Danny Bonaduce.

Bonaduce later appeared as a contestant on the show, competing against The Courtship Of Eddie’s Father’s Brandon Cruz and The Munsters’ Butch Patrick.

Blumenthal: You want [the host] to get out of the way and to allow the contestants to be the stars of the show. You already have something funny and something really entertaining in a wonderful environment. You need to find somebody who looks as though they would belong in an environment without dominating it. When Ken came in [the interaction was right], because Colin is such a very specific personality and we wanted somebody who would be very different from him. But we also wanted to believe him if he said he was doing a game show in his basement.

Michael Dugan, co-creator: Colin still had a little bit of an attitude [even after he was cast], because he still always wanted to host the show.

Quinn: I was better [at the game] than Ken. I felt disillusioned. I’d go to Ken, “You know, that was the episode where Cindy…” and he’d say, “I didn’t watch the fucking Brady Bunch.” I was like, “Ken! Please!” Even I was shocked by that.

Davola: Colin’s better talent was when Kenny would go, “Colin, what do you think of the contestants?” and then Colin would rip every contestant apart. He’d call every contestant out and goof on him.

The show was also filling out its cast of players elsewhere, nabbing in-house musician Steve Treccase to act as its bandleader of sorts.

Steve Treccase, musician: I was on staff in the studio production department, so I had an inside advantage. They were doing test rehearsals in one of the conference rooms and they invited me to join. I just schlepped in a couple of keyboards I had at home and an old drum machine, along with a little amp rack, and I set it up in the conference room and played along.

In the beginning, there was a much lighter approach to the music they wanted. We actually used the word “cheesy.” We wanted cheesy game show music. So that’s what I was doing.

The show also sought to cast Quinn’s female sidekick, a role that would be recast several times throughout the show’s run.

Corrao: Part of [wanting a female sidekick] was that [Wheel Of Fortune’s] Vanna White was so popular at the time. Before we actually had [season one’s] Marisol [Massey], we called the character “Vanna.”

As to why we went through so many of them, I think we were always looking for the equivalent of Colin, and I’m not sure we ever found it. Everybody has their favorite, for sure. Kari [Wuhrer] lasted the longest and was the most well known. She managed to break out in a way that the others didn’t. But, again, there was not a whole lot for them to do beyond sort of reacting to the game that was being played. Even Vanna had a much more of a specific function than our female characters did, sadly.

Other Remote Control cast members hired around the time included Emerson alum John Ten Eyck, who played multiple characters throughout the show’s run. In later seasons, Leary and an NYU student named Adam Sandler were tapped as frequent visitors to Kenny’s Basement at 72 Whooping Cough Lane.

Leary: When the show was first taking off, they mentioned to me the idea of doing it, and I can’t remember what the hell I was doing. I think I was doing a play in Boston; making no money sounds crazy, but I was committed to whatever that play was. You sign up for a three-month run, and I think [the play] ran for two weeks. So my memory is [the Remote Control team] talking about me doing something and [me] going, “I can’t because I’m going to be in this play for three months,” and then two weeks later watching those guys on TV and going, “Fuck.” The show took off. Immediately they were like, “We’ll just bring you in next season.” I think it was only to be Quinn’s brother, because I had this idea that I didn’t play characters. I’ve never been a character guy. My stand-up was all my point of view.

Sandler came into the picture after Herzog stumbled into seeing his set one night at a comedy club.

Herzog: He’s wearing stained sweatpants, sneakers, a dirty T-shirt, and a hat on backwards. He was literally a college student, and I thought, “Oh, that’s the audience.” He had a vaguely Jewish Beastie Boy vibe. I can say that because I’m Jewish.

I was just like, “This kid should be on MTV,” so I followed him out to the lobby, gave him my business card and said, “Call me.”

Mike Armstrong, head writer (seasons two and three): Doug says, “I’ve got this guy. He’s going to come in and meet you and talk about some ideas.” So Adam comes in and he starts describing this character he wants to do called Stud Boy. He says, “I’m wearing a robe and I have a Latin accent, and I’m romancing the older woman. Oh, my darling, come here. We must find…” You know. And I’m just standing there beside myself because I don’t get it at all. I’m going, “Oh, my god. Poor Doug. What’s wrong with this picture? He can’t pick talent.”

This is before Adam did SNL. I mean, Adam has turned into the highest paid comic actor in a generation. How wrong could I have been? And by the way, when he came out on stage, from the first moment he just had that thing where you see him and you know you’re looking at something extraordinary.

Herzog: Quinn knew him from the clubs, and Quinn was always a huge fan. I remember that in Adam’s early performances, he was doing Stud Boy and early versions of his characters, and it was just absolute crickets. The only person laughing is Quinn on the side of the stage. But Adam, that was lightning in a bottle there, and before we knew it, he was gone to SNL.

Armstrong: [Eventually, Sandler would] walk out on stage and the audience would go nuts. They couldn’t wait to see Adam.

Keith Kaczorek, writer: Sandler added to the sense [that it’s the college audience’s] show because he was one of them. It’s like, “Here’s the funniest guy in your dorm.”

Dugan: He was still going to NYU while he was doing the show.

Davola: I used to go to Adam Sandler’s dorm at NYU with my wife, who was my girlfriend at the time. We’d go drink beer in his dorm.

Though working at MTV might have seemed like a dream job for comedians seeking exposure in the mid-’80s, it didn’t actually pay all that well.

Davola: I don’t even know why [Leary and Sandler did the show]. They all looked up to Quinn, maybe.

Leary: Everyone made no money, relatively speaking. None, none! But we didn’t give a shit because—listen, I was still doing plays off-off-off-off-off-Broadway. You go to auditions and then you do stand-up gigs, which you don’t get paid to do in the city. Maybe you’d get 15 or 20 bucks at that time, but you’re doing them just to keep your skills sharp. And then you go uptown to the studio the next morning and you work all day and shoot four shows and—it was not this, but it was pretty close to it—but you make like $400 for four shows. That’s a lot of money.

My rent in Boston was $250. My rent in New York was $250, so $500 for two places. They were shitholes but who cared.

We laughed so fucking hard. We’d be backstage just watching the monitor. If Sandler goes out, you’re watching, waiting to see what he’s going to do and you’re laughing your ass off. Then you’re laughing your ass off again, not at the questions, but you’re just laughing at Kenny and Colin and what they’re saying to each other. You’re watching Ten Eyck do something fucking bizarre. It was a blast.

The show was a rather low-budget affair across the board. Though figures differ, Dugan and Davola say that each episode cost about $7,000 to make, with MTV additionally footing the bill for some of the producer’s salaries, since they worked on other shows. That added up to about half a million dollars to make 65 episodes of TV—one season’s order. Corners were cut and departments were asked to get creative. The show’s set design, for instance, was practically held together with spit and duct tape.

Davola: When you sit down with a set designer, you tell them what your vision is. Mike [Dugan] and I talked about the basements in our houses, because when you grow up in the ’60s and ’70s, all the shit from the ’50s and ’60s goes to your basement. That’s where the Barcalounger would be. That’s why there was a washing machine and a dryer. All that stuff was in the basement.

Taylor: I was working in New York on Double Dare. I think the only time we actually shot Double Dare in New York was in the summer of ’87. Geoffrey Darby, who was the V.P. of production [at Nickelodeon] had given my name to Joe Davola over at MTV. He called me and I came in. He gave me the pitch or whatever the logline for the show was and talked about what he needed. Anyway, I went away and came back with the design. At that point, he had at least two or three other people working on it simultaneously. All of this was on spec, which was fine.

I centered it in the basement. Originally, I was going to do a garage, because that was what I was familiar with growing up in California. I’d never seen a basement until I got to New York. I based it on the basement in the house where my wife grew up in Queens. They had a finished basement, but it led out directly to a garage or something. It was very strange. They had a fish tank built into the wall.

So I took some of those kinds of things and the garage idea, and I guess he liked it. It was different than everything else that was done. There was somebody that had a cartoony living room set. I can’t remember the other one that I saw.

Davola: [Taylor] did an unbelievable job, especially because we paid basically no money.

Ezor: The remote that you held [as a contestant] was basically a block of wood.

Taylor: The budget was so tight that we borrowed the scoring system from Double Dare. So those digital displays that were in the front of those little side table things and the actual mechanics that run all of it—that was all from Double Dare. There was a lot of set dressing, too, that people brought in. I hope they got it back. I don’t know if they did or not. One guy brought in his collection of old board games from the 1960s. We put those on top of the refrigerators.

Taylor and his team also figured out the functionality of the show’s “snack breaks,” which happened at the end of the first round of play and featured various junk foods being delivered to the contestants in oddball ways. Most of the time, the snacks were just dumped on the contestants from above.

Susan Bolles, art director (seasons two through five): If you were looking at this set, the chairs were up on a platform and then they had the TV tables with the scoring system in front of them. And that was actually pretty far away. Everybody wore seat belts because one of the chairs flipped back, and out of fairness for the contestants they all needed to be in seat belts so that they were treated equally.

The buckets were probably 8 feet up. It was a big metal rig that had buckets and then it was just pulleys and ropes. The stage hands behind the wall would pull when it was time and it would trip all three buckets to dump. Usually the guys liked to do a little dump and then they would dump it all. They liked to tease the contestants like, “Yeah, you think you’re getting off easy? Wait for it. Here it comes.”

Taylor: If you dropped potato chips on somebody or popcorn, that was all well and good. But if you put something up there like malted milk balls or gum drops, the heat of the television lights would melt all of that stuff together even in just the short time that it would be up there. All that stuff would begin to stick together, and then it got flipped down and dropped on somebody’s head. There were complaints because it was basically like dropping marbles on somebody, especially if you were using hard candies and stuff like that.

Bolles: You couldn’t do liquids because everybody was miked. So the very first thing you worry about was the audio equipment getting any liquids in it. I mistakenly used chocolate milk powder for an episode, and you can’t do powder because friction in the air can cause a powder to ignite. We couldn’t have that as an issue. Plus, the guys didn’t like the clean-up, so you couldn’t do powders.

A general rule was anything bigger than a jelly bean [was good], but it couldn’t be hard so that it hurt people. So, sour balls were probably out cause they would hurt falling at a distance. We used a lot of cereal, marshmallows, definitely candies. Gummy worms. We would try to pair things with whatever the writer’s theme was for the particular show.

Rob Johnson, contestant: Our snack was Franken Berry. Dry cereal came down and they gave you a little school carton of milk. [Producers were] off camera, like, “Throw it around! Throw it around you!” [You’d have a 30-second] food fight and then they’d say, “Okay, [let’s] clean up.”

Another key component to the show’s set was Ober’s wall of game show heroes, which featured headshots of various hosting legends like Bob Barker, Bert Convy, and Monty Hall. Close by sat a roughly human-sized Pez dispenser shaped like game show icon Bob Eubanks.

Corrao: I was the one that had to write to Bob Eubanks to get his permission to use his likeness. It originally started off as Wink Martindale, but he said no.

Taylor: There was one shop that used to build a lot of the giant props for Double Dare so they could do carving of foam and stuff like that, so they got a headshot of Bob Eubanks. We didn’t have a profile, so if you looked at it from the side, it wasn’t perfect, but we scaled up a Pez dispenser.

Dugan: [Bob Eubanks] eventually came on the show. We have pics of him with his Pez head, and then he went through all these little details on the head and said, “well, I’ve had plastic surgery on that, so that should be a little different.”

At the same time the set was coming together, the show’s writing team was being assembled.

Dugan: When I was talking about it back then, in the early days, my biggest influence was The Gong Show. Growing up, I used to watch it every afternoon. I loved Chuck Barris, and the fact that he didn’t seem to take anything seriously. I just adored that. It was hilarious. So that was the attitude that we wanted to go for, which was just to keep it loose. Don’t make it seem like anything really matters because we’re just talking about TV. We’re just having fun.

Armstrong: I got a call from Doug [Herzog] and he said he wanted me and this other guy we went to school with, John Ten Eyck, to come and do the show.

We first had to do a written audition so we went to the New York Public Library and wrote a bunch of crazy nonsense about pop culture one afternoon, and they gave it to the head writer. I don’t think he had much choice in the matter. Doug wanted to bring us on, so even if our written material was terrible, which it might have been, he still had a gun to his head and was forced to take us on. And that was how it happened. Doug was kind of running the network, so what Doug said went.

Rosner: I was 27. I just graduated high school for the second time using a fake ID. I was living in New York with my girlfriend who’s now my wife and I had been pretending to be 17 and 18 for a year for weird reasons. Like, upon graduating high school, I ceased being 18 and I missed it. So I was going around New York City looking for work being an art model. I was at Fordham University where they had one of those sheets with a little tear tabs looking for contestants to come play a game in development for MTV. They were looking for people 18 years old. I was like, “Oh, here’s one more chance to be a teen again.” I showed up and I played the game and I pretended to be stupid because I figured, “It’s an MTV game. I should be stupid.” They had me back to play for the execs, so I played a second time and the show got greenlit.

I just really liked it. I had never been around people like that before. Everybody was funny and I mostly worked in bars and people weren’t that funny. So I was like, “Can I work for you guys? You don’t have to pay me. I’m not really as stupid as I was pretending to be.” And they said, “Sure, you just have to be getting college credit somewhere.” So I forged a letter from the Fashion Institute saying I was getting credit for interning and went to work as a fact checker.

Armstrong: [Dugan, Herzog, and Davola] had a vision of what they wanted. It was hard to articulate because it was like trying to articulate a painting. What was it gonna look like? I‘m not comparing a game show to a painting, but they wanted a certain attitude. We had to be there for weeks and weeks and weeks before we started to get the attitude, because the attitude reflected what was going on in the writers’ room and in the offices at MTV. Dugan was very good at articulating—as well as he could have—that attitude. We would turn in questions and say, “What’s the matter? It’s a good question.” He’d say, “It’s too dry. Take it back.” I didn’t know what he was talking about really, because I didn’t know what the show was. He kept bringing the material around and bringing it around and we slowly started to get it. We started to see what he was saying. By the time we got on the air we all sort of got it, but I don’t think anyone got it at the beginning except those guys—even the hosts or the people who came in to audition.

Eventually, the writers began to come into their own, molding a traditional game show’s straight-laced format into Remote Control’s twisted take on pop culture.

Kaczorek: It was, “Are we making fun of TV or are we making TV? Or are we doing both?” And we were doing both.

Rosner: There was a category “Toupee or not toupee,” which was just “Which celebrities wear wigs?” I liked having categories like that because I could just pump out 70 questions under that umbrella.

Davola: It was nine channels, three questions. So you go through 54 questions a show, though you can carry some over if you didn’t use them, but you have to prep that many just in case they ran the board. That’s a lot of questions, especially multiplied by 65 episodes, which is what we were shooting over 13 weeks.

It was a very “anything goes” sort of situation with the [writing] team. If somebody came up with something, we tried it. One of the guys was laughing theme songs over the intercom system. I looked at [Dugan] and said, “That’s a channel. He said, “You’re crazy,” but we created the Laughing Guy, who laughs theme songs and you have to guess it.

That’s how we came up with Sing Along With Colin. Was Colin a horrible singer? Yes, but everybody wants to be a rock star. Let’s give them a mic. So we knocked out another category.

Armstrong: Rick Rosner came up with a channel called Brady Physics. That, to me, was the quintessential Remote Control category, because it combined actual real life challenging knowledge and questions with absurd and obscene concepts.

Rick came up with stuff like, “Alice on The Brady Bunch settles up the grocery bill with Sam the butcher on the kitchen table. If Sam weighs 220 pounds how much force per inch will Alice experience?” Stuff like that. I just thought, man, I want to be working on a show where that’s a question. That kind of stuff made it worthwhile to me.

Kaczorek: I wrote a thing called Inside Tina Yothers, which was obviously an entendre. Family Ties was going strong. Here’s one I pulled out of my stack of questions: “Captured by a rival network, Tina Yothers bites down on a cyanide capsule rather than breaching her contract. Does she die in about 10 seconds, 10 minutes or two hours?” And the answer, of course, is 10 minutes. The movies would have you believe it’s 10 seconds, but it takes a little bit longer than that.

Armstrong: We had a category called “Dead Or Alive?” the first year. These two writers Ron Helgi and Charlie Rubin came up with it and it was great. At the beginning of season two, I was head writer and I was looking for something to replace that because you couldn’t go too far with it. I sat down and within five minutes I went, “Oh my god: Dead, Alive, Or Canadian.” Because I come from Canada. That was my best contribution. And then I got to come up with a theme song.

There were people like Lorne Greene from Bonanza, and he was a dead Canadian, so if you said both, you’d get double points.

Corrao: There was so much we wouldn’t do now… “Dead, Alive, Or Canadian?” “Dead, Alive, Or Indian Food?” The “Dead Or Alive?” channel pushed the envelope just in the sense that we were joking about whether or not someone was dead or alive but running the risk that they might die by the time the show airs. I think it never happened, but we had to be super careful.

McPaul Smith, writer: There was a hit song called “Bette Davis Eyes,” so we took Bob Giordano or one of the other writers who was this skinny white kid, we put a wig on him, and he was going to be Bette Davis doing exercise. At the time, Bette Davis was an 86-year-old dying movie star, so we thought it would be really funny to just put him in a Bette Davis costume. We said, “We can give him a cigarette and have him do aerobics and then turn that into a question.” I can’t even remember by what conceit we turned that into a question about TV, but we did.

They shot a bunch of those and they were funny, but then, of course, between the time they shot and the time they rolled the season, Bette Davis died and it was like, “I guess we can’t do Bette Davis anymore.”

Corrao: If [a contestant] hit a specific channel, the doorbell would ring. Somebody would walk in and they would basically do a bit either with Colin or with Ken. With Denis and Colin, their whole bit was that they were brothers and they would just fistfight each other, and then at some point it would stop and Ken would ask a question.

Kaczorek: It was always good working with John Ten Eyck. He would do the goofy characters. I wrote a lot of the Ranger Bob stuff, so we would send him as Ranger Bob off to some foreign country or whatever and give him a horrible disease, and people had to guess what it was.

Smith: We came up with [a lot] of theme shows. We did a tribute to the remote control. A tribute to to adhesives and lubricants. Just shit like that. We did a tribute to lunchmeat. They had done a tribute to underwear episode—I came in [for my interview] and said, “Well, you could do a tribute to to lunch meats, and then instead of Beat The Bishop, you can do Beat The Baloney. We’d dress Ten Eyck up like a piece of baloney and have him run around.”

With all components seemingly in place, the show began taping. Because of rules around game show production, there was a bit of a learning curve.

Dugan: Our first priority was trying to be funny, but we learned after shooting a few episodes and watching them that it has to really feel fair the whole time. We had some things like, if you pick one of the channels, you’re off-the-air.

Davola: And if you’re in the lead, you’re the one that’s getting screwed, because you’re pulling all the categories. We realized after watching it that kids weren’t going to like it because they like things that are familiar but different. They don’t like it so different that when the person that’s in the lead picks a category, they lose all their points and are gone from the game. Then why are you even clicking on categories?

Calderwood: We had to learn that if there’s a horse race between two contestants, you have to play that up. The host has to play up game elements to pull the audience in, whereas most comics are just looking for the next event to hang a gag on or to get a laugh from, and that would sometimes be at the expense of the game. [People at home] just want to watch the game when they’re rooting for this player or that player.

We threw out all the rules and then we had to slowly learn why the rules were there. And then we bent them after a while. We didn’t just break them.

Corrao: We were all really young and no one was telling us what to do. We had to figure it out. Being out on the floor in those early days was chaotic. One of my favorite moments was when a stage manager got the [eliminated] contestant wrong. The person knew that they didn’t have the lowest score, but all of a sudden they were flipped through the wall and everyone’s expression was just like “Oh my god, what do we do?” Technically, it’s really difficult when you stop tape on a game show because once you make an edit, you have to put up a disclaimer and say that nothing changed in the score and none of the rules changed. The idea was you shot from beginning to end of a show without ever stopping tape. And that was one of those big moments where we had to stop and recreate that moment because it wouldn’t have been fair to pull that person out of the show.

Calderwood: Now you cannot do a game show without hiring what’s called a compliance lawyer or compliance division. They come in and just read you the riot act about how, for example, you can’t leave any papers out that could have any game elements on them because possibly a contestant could see them by accident. It’s very buttoned up. All of that was just the exact opposite of how a bunch of 20-something kids were at MTV. We couldn’t be bothered with that type of thing.

Rosner: I was responsible for a show that didn’t air because I fucked up the research. I’d forgotten that The Incredible Hulk had two names. In the comic books his name was Bruce Banner. But in the ’80s, Bruce was considered to be a “gayish” name, so for TV, when they made the Ferrigno/Bill Bixby show, they changed his name to David Banner. So a question came in, “What was The Incredible Hulk’s first name?” and the answer said David Banner. [As a fact checker] I’m like, “That’s fine,” and I did a half-assed fact check because I knew it was right. And then the question got asked and the contestant said “Bruce Banner” and they buzzed him wrong. But that’s a correct answer, and it wasn’t fixed. We didn’t say so on the TV show anyway. The kid didn’t get the points he deserved, and the kid complained. It fucked up the outcome of the show, and they never broadcast that episode.

Everybody at Remote Control was nice to me and said, “It wasn’t all your fault. There were other things wrong with that episode,” but I don’t know. I don’t know whether anybody got the prizes that they had won, which were pretty good prizes.

Quinn: One time [Kari Wuhrer and I] said, “[This contestant isn’t] going to get that last video [in the bonus round] and it’s not fair.” The last video was too hard, and we wanted somebody to win the Mitsubishi Montero. So we used to be there grabbing the person while they’re on the bed, and right at the end we both whispered [the answer] in his ear. He won the car.

Armstrong: At the risk of maybe insulting a couple of people—although I don’t think they will be—some of us were so inexperienced. We didn’t quite understand what the pressure was. We would do four or five shows a day, and we would just race through them. It was a blur, though everything worked really well. I only remember a handful of times where we had to stop taping and reset something. Part of it was that there was a chaos to it that you kind of wanted. You didn’t want it to feel entirely polished, and I think that’s what people liked about it.

Quinn: They let me smoke cigarettes on the air. I mean, what the hell?

Though tapings of the show felt good once the kinks were worked out, the true barometer of the show’s success came when Remote Control finally premiered on MTV in December 1987. Once episodes started running, it quickly became clear that MTV had a winner on its hands.

Herzog: Double Dare was a big hit, and so we felt the pressure to make our show a hit because there was a lot of internal rivalry. Nickelodeon was led by Geri Laybourne, and they were sort of like the smart kids in the class. They were the “sit up front and ‘Teacher, you forgot to give us homework’” kind of kids. We were the kids in the back of the class with spitballs who always get in trouble.

Davola: [Ken and Colin] loved making the show, but before it aired, they were a little unhappy because they were comedians, and their comedian friends were busting their balls about doing an MTV game show—or really any game show, period. So they sort of felt like loser comedians who did game shows because their careers were on the wane or something like that. But they became immensely popular [quickly] and their attitudes changed probably after the third week of the show.

Quinn: Who the fuck, at that age, in their first big thing, is that disgruntled? Only I could be that disgruntled over a thing.

Armstrong: [Later, during the third season] as I remember, Ken and Colin were hanging out and Ken was complaining because he wasn’t doing stand-up comedy on shoot days. He was in a bad mood one day and he was complaining about the show and saying “I’m not out there doing comedy or doing a sitcom or a movie or anything.” He wanted to do something more pure.

Anyway, they were in Florida [where the show filmed its third season, and several Spring Break runs] and a girl comes up and says, “Would you do me a favor?” And she pulls her top down, hands him a Sharpie, and says, “Will you sign my tits?” So Ken signs, hands the pen back, looks at Colin, and Colin just goes, “How do you feel now, Spalding Gray?”

Leary: It was pretty fucking crazy because the show had taken right off, and you could tell by these audiences that they bring in. They weren’t having to fake the audience [enthusiasm], especially after the first season. They were rabid fans. It was crazy. You’d arrive at the studio and there’s people lined up outside and they’re crazy fans. So you’d think, “Oh fuck, this thing’s big.”

But when you go to Florida [for Spring Break], it was really insane. Kenny and and Colin were fucking rock stars. There’s people waiting outside the hotel for Kenny and Colin, to get their autographs. When you get to the set, it’s a wall of drunk people, girls and guys just screaming for Kenny and Colin.

That’s the point, I think, where we all thought we were going to make more money, which of course, we didn’t, because though the whole idea of MTV was built on, “We make you into stars and we don’t give you any money, and right when it’s time to give you money, at the beginning of the fifth season of something, we get rid of you.” But we didn’t know that.

Herzog: This is tough for twentysomething kids to get now, but I say to them all the time, “I know it sounds ridiculous, but MTV was YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and Tik Tok all rolled in one.” It was the only thing that young people paid attention to. If you were under 25, nothing was bigger than MTV and the people that were on MTV. So whether you were a rock star or a VJ or Colin and Ken, you were huge stars. We would roll into Daytona Beach [for Spring Break] and there’d be 40,000 kids, 50,000 kids just going apeshit. I mean, they’d be going apeshit anyway, and then MTV rolls into town. They all want to be on TV and they all want to meet everybody.

Quinn: Literally we’d go, any place in public—like New York walking in the street, to an airport or whatever—and we’d get swamped. People would [look at us and] go, “Who the fuck are they?”

It’s so funny because about two years ago, I was walking down the street, and I think it was Jake Paul or somebody from YouTube, and the exact thing happened. It was like 50 kids going crazy, and I was like “Who was that guy?” It reminded me of those days.

Leary: Do you remember when Oliver Stone did the movie about The Doors? I got a fucking phone call from my agent at the time. He goes, “Listen, Oliver wants you to come in and audition for a movie he’s doing about The Doors. Andy Warhol is a character and he wants you to audition because he saw [Leary playing Warhol on] Remote Control.”

I was like, “Dude, that’s not Andy Warhol. It’s me in a wig doing some crazy fucking thing. I can’t be Andy Warhol.” I was like, “Are you fucking sure that somebody is not just fucking with us?” but then I got a phone call from Oliver Stone. So I went to a meeting, not an audition. I sat down with Oliver Stone and I said to him, “Listen, you understand, I don’t really play the guy. It’s just a bit that I do on the show.” And he’s like, “I thought it was a character that you do.” I go, “No, no, no, it’s not.”

Anyway, I didn’t get the part. But then he hired me a few years later. I did a part that was eventually cut out of Natural Born Killers. But that’s how I got that part in Natural Born Killers—because he was watching Remote Control. So, think about that. Oliver Stone watching Remote Control is, to me, so crazy.

Between Remote Control’s first and second season, the show capitalized on its popularity among 18-22 year olds by taking its hosts and game on the road, hitting various colleges across the United States.

Quinn: We’d go to Missouri. Illinois. People would be like, “Wow, these guys are here.” It was a big deal like that.

Corrao: Colin really took off as a character on the show’s college tour [between the first and second seasons.] I think he almost usurped Ken in his popularity.

Quinn: By the way, my comedy was not up to the level that it needed to be, but people would just be like [Mimics drunk yelling.] “Ayyyyyy, Colin Fuckin’ Quinn! We don’t give a shit!” I’d be like, “Hey, wait a minute. I want you to be able to get my act,” and they were like, “Oh, whatever.”

The A.V. Club: Did you get a lot of college gigs?

Quinn: I’ll tell you, I did. They’d be screaming [when I came on stage, but] they didn’t care. They would laugh politely like, [Whispers.] “Hey, this is what he likes to do, man, so listen to him.” They weren’t enjoying my jokes. They were just like, “This is the guy’s gig. He’s alright. He’s always funny enough.” But afterwards, I would just sign autographs for two hours.

Leary: [Colin’s] act was never geared towards college kids anyway. It was much edgier and biting than the kids that were in that audience. When he did stand-up, he didn’t give a fuck about the fact that you knew him from Remote Control. That was the last thing on his mind.

[Colin and Ken] were huge. ’87, ’88, ’89, even up to ’90, those guys, man, if you went with them to do anything. We shot a thing at some bar as part of the show. It wasn’t Remote Control but it was connected to that and to MTV. It was the Remote Control cast and Kenny and Colin. There was an audience of 200 kids inside of a bar and they were shooting like a 15-minute piece, and fucking Guns N’ Roses showed up because they were fans of the show. They were outside talking to fucking Kenny and Colin like they’re talking to fellow rock stars. That’s how big they were.

Even Remote Control’s staff managed to enjoy some of the runoff from the show’s success.

Kaczorek: We could get into any club in New York if we had one of the producers or executives with us. You’d just flash that MTV business card and the velvet rope went up. And this was in the late ’80s, early ’90s, when that was the thing in New York. It was still a hangover from the Studio 54 days and all of that “you look cool enough to get in” stuff. So a gaggle of us would go over to the Palladium or whatever and go up to the guy at the front of the rope and just get in.

Dugan: I was too naive to know what was happening with the show on the air. It got ratings, but I think MTV ratings were different? I felt like everybody watched it, but it only got a 1?

Davola: I think it was getting 2-somethings when we first got on the air and then it was living at around a 1.7. But [MTV] would basically give [Dugan and Davola] half a billion dollars each if they could get a 1.7 every day now.

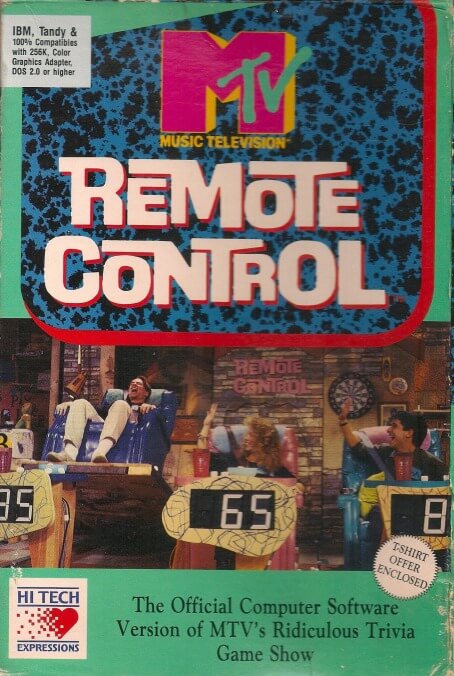

Dugan: Back then, It was like, “Well, we’re gonna do like a home game. We’re gonna do a computer game. It’s gonna be syndicated. We’re gonna take the show on a college tour,” And I just was very naively like, “Yeah, that’s what happens. Everybody does that.”

Flinker: Being at MTV in the late ’80s, early ’90s was like being in the best high school ever. Every day you would skip to work just because people treated you so well there. If the show came in and did really great numbers, they would literally take you to Atlantic City by bus and give you 100 bucks each to go gamble. That’s how they treated people. They would send champagne.

Imagine doing that in the TV world now. Now, you’re lucky if you get a thank you email.

Even though the show was both thriving and syndicated, MTV decided to walk away from Remote Control after its fifth season. The last episode aired on the channel December 13, 1990, only a little over three years after it had first premiered.

Davola: MTV wouldn’t ever take [the show] off the air now. They would keep it on forever.

Herzog: We used to have this mindset that nothing was really built to last because we were never going to do what Rolling Stone did, which was grow old with the audience. We wanted to constantly reinvent ourselves as a company so we could evolve and appeal to the next generation of young people. If anything ran like three or four years, that was great. And so the idea was to do it and do it until you overdo it, and then when it starts to [get stale], get out and find the next thing.

Davola: The second time I came back to MTV [in 1993, as senior vice president of development and production] there were conversations about, “Let’s end The Real World.” I had worked at Fox [by then] and I said, “You don’t end The Real World. You continue to do The Real World, and you do a spin-off,” and that’s how we worked on Road Rules. I had learned from going to a network that when you have a hit, you hold it by the tail. At MTV, the mindset was, “We can do it [from scratch again] ourselves.”

Despite its relatively short tenure on the air, Remote Control left a lasting legacy. Its legions of fans and contestants remember it fondly. (The show boasts a shockingly robust fan-made wiki, which includes episode recaps, contestant names, and hilariously dated prize listings.) The people who worked on Remote Control went on to other TV jobs, taking with them the scrappy and offbeat upstart mentality they learned from the show. But many of them remember working on Remote Control as a job that, in many ways, tainted them for future work.

Quinn: When I look back, [I think about how] the show was so loose that they would let us get away with stuff. They would let you flow and do whatever idea you came up with. Just screw around. There was no, “Hey, guys, remember to do this.” It was like, “Do what you want. This is supposed to be fun.”

Blumenthal: In some pretty impressive ways for me, the learning was, “You can go further. This is the beginning of something. This is not an aberration.” We’ve changed the way we think about deconstructing formats.

Rosner: Remote Control addressed an area of knowledge that everybody has and had never previously been quizzed on before. Also, it was a fucked-up show. We dropped food on people at the end of every round.

Smith: What was another comedy game show before that? I don’t know that you could really point at another comedy game show that wasn’t wacky and messy.

Treccase: [Remote Control was] a classic hero’s journey disguised as a game show. Here was a guy who created an entire universe that he could control in his basement for a certain number of hours a day until it was broken up by his mother and he was returned to the conventional world, with all of its artificial construct that he could not control. It was Wagnerian opera and Ken was Siegfried.

Leary: It’s weird because—I’m sure it’s the same for Colin and for Sandler, even though I’ve never talked to them about it—but every once in a while, when you’re coming out of a building or you’re doing a bunch of press stuff, you’re going into a television studio or whatever, people have pictures and they want to get autographs. And whenever you’re doing that, every third time there’s a person with a fucking Remote Control picture. And I always say, “Where the fuck did you get this?”