Bafflingly fixated on corporate intrigue—which gets more attention than Tom’s family or the whole cat angle—Nine Lives finds Tom reluctantly buying Mister Fuzzypants for his daughter’s 11th birthday, only to change places with the cat after being thrown off the roof of his nearly completed Manhattan tower. Does that mean the poor cat’s mind is trapped in Tom’s comatose body? The movie raises this question, but never gives an answer. It does, however, suggest that the souls of the dead and otherwise physically indisposed often inhabit the bodies of cats, with eccentric Manhattan “cat whisperer” Felix Perkins (Christopher Walken) as their guide. Perhaps Tom is right, and cats are simply soulless fur balls on whom the weak and lonely project their own feelings.

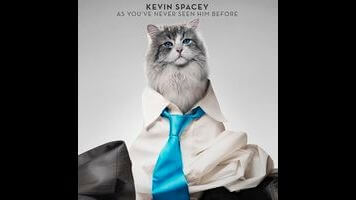

Supporting this hypothesis is the apparent lifelessness of Mister Fuzzypants, played by a combination of real, bored-looking cats and suspiciously flexible CGI facsimiles; his little cat mouth never opens, even when meowing. Spacey’s glued-on hairpiece, given prominent placement by Sonnenfeld’s tendency to frame the actor front and center early on, isn’t much more convincing. As with so many movies made to low standards under the assumption that their target audience isn’t old enough to care, Nine Lives generates it own cut-rate surrealism. Very little of it makes sense, even when accounting for human-feline mind-swaps, and everything is cheap, from the recycled gags (two cat-piss jokes, two slow-motion sequences of people tumbling over while trying to catch Tom in Mister Fuzzypants form, etc.) to the small, cramped sets and shortage of background extras.

An ordinary family-matinee fantasy might use this magical scenario to humble a careerist like Tom, but Nine Lives gives most of the life lessons to his two children (Robbie Amell and Malina Weissman), who discover just how much their dad loved them—and, in the son’s case, how to be “a man”—while Tom’s empty body languishes in a hospital bed. So what does that leave for Spacey’s indifferently voiced cat-man? The movie, which is nothing if not a fascinating text, pits him against corporate usurpers, very literal castration anxieties, suspicions of infidelity on the part of his wife (Jennifer Garner), and the machinations of his dog-owning harpy ex (Cheryl Hines). This is one of those cases where a skyscraper isn’t just a skyscraper.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.