Kim's Video review: A nonfiction work of swirling whimsy and rabbit-hole intrigue

While celebrating a legendary independent video store, a documentary filmmaker hatches a plan to steal a movie—or 55,000 of them

As any cinephile well knows, the physical places that serve as meaningful ports of entry to our love affair with cinema can often take on swollen, totemic value. It’s fitting, then, that one of the most legendary independent American video stores of all time gets its own beautifully odd little curio in the form of Kim’s Video, a nonfiction work of swirling whimsy and rabbit-hole intrigue that eschews mere nostalgic appreciation in favor of a cockeyed hybrid approach that amuses and bemuses in equal measure.

The mysterious nature of the owner of Kim’s Video in New York City could perhaps only be matched by the strange fate of his massive, laboriously accrued home media collection following his flagship store’s 2008 closure. This festival-minted offering (it premiered at Sundance last year, preceding stops in Sydney, Tribeca, Telluride, and elsewhere) luxuriates in questions surrounding both, and thus ends up being a movie about personal obsession as well as complex ideas about the ultimate ownership of art.

At the ostensible center of Kim’s Video, helmed by the husband-and-wife directing team of David Redmon and Ashley Sabin, is Yongman Kim, a South Korean immigrant who arrived in New York City in 1979 at 21 years of age, fresh out of the military. He opened a dry cleaners but, loving movies, decided to also stock it with several videos for an underserved community, as a source of ancillary income. While the dry cleaning business foundered, his collection of quirky, hard-to-find videos took over, so Kim pivoted.

At the height of his success Kim had seven video stores, most notably Mondo Kim’s on St. Mark’s Place, which boasted 55,000 movies and a whopping 250,000 members. The lovingly staffed, bohemian venues were a cineaste’s fever dream (employees included, at various points, Todd Phillips, Alex Ross Perry, and Kate Lyn Sheil, among others), where high art and low art were joyously intermingled and films from name-brand auteurs heretofore unreleased Stateside existed alongside gritty DIY offerings and bootlegs of titles with dubious legality and colorful chain-of-custody issues.

Eventually, though, Kim’s Video succumbed to the same fate of so many brick-and-mortar establishments. In the wake of its closing, Kim accepted a strange, brokered proposal to export his vast physical media library to a 3,000-square-feet exhibition space in a small town in Sicily, Italy.

Salemi, still feeling the after-effects of a devastating 1968 earthquake, is not so different from small communities all across the globe, cordoned off from economic opportunity without some creativity. Sensing the chance to reposition itself as a cultural hub, Salemi promised to digitize the entire collection, give free access and rentals to former Kim’s members (including a limited number of on-site sleeping quarters!), and establish a “never-ending festival” that would take the form of a continuous public screening culled from Kim’s archives. Needless to say, these rich promises didn’t exactly come to fruition.

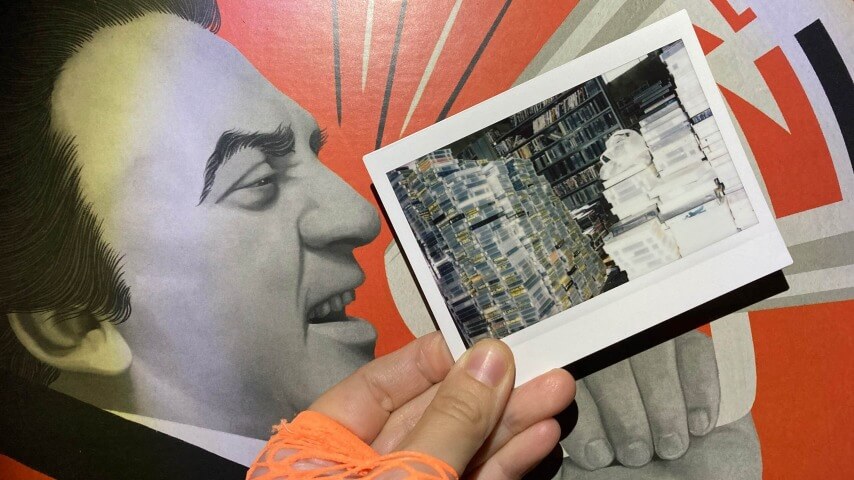

It’s in this curious space that most of Kim’s Video unfolds. Redmon visits Salemi, and finds the VHS tapes and DVDs poorly stored and largely neglected. (On the ground outside the building in which they’re housed, “crime scene” is graffitied, in English.) From here, Kim’s Video morphs into something loose-limbed, a mixture of art school project, spy flick, and heist film.

Redmon connects with Kim himself (a fascinating figure, even if not quite fully explored here), and then attempts to track down the weaselly former mayor of Salemi, Vittorio Sgarbi, whose friends include scandal-plagued Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and several others with mafia ties. While the results of this investigation seem not so much sinister as garden-variety corruption and breach of contract, Redmon views the erasure of this library as an offense that cannot stand. Taking stated inspiration from Argo, he eventually latches onto an audacious scheme: to steal back the collection.

Any honest analysis of Kim’s Video does well to frame it much more as a personal cinematic essay than a conventionally-oriented documentary. The movie indulges Redmon’s biographical background (he narrates throughout), charting his journey from rural Texas to New York.

True, a deep roster of former store clerks provides anchoring context for Kim’s video empire, while a number of recognizable ex-members (actor David Wain, film critic Dennis Dermody) also pop up; absent are the Coen brothers, who apparently rang up $600 in late fees.

Mostly, though, Kim’s Video aims to serve as a vessel for its maker’s fixation. This means a heavy rotation of clips from obscure titles, as Redmon, for example, compares the store’s shuttering to Abbas Kiarostami’s Where Is The Friend’s House?, and talks at various times about hearing voices guiding him in the making of his movie, and heeding their call.

Whatever one’s threshold for this type of comparative analysis and higher-calling rationalization, Redmon and Sabin’s film slyly absorbs bit players and potential antagonists into the larger fabric of their cinematic collage. A standoffish local police chief becomes somewhat fond of the camera, and a willing interview subject; Enrico Tilotta, whom we first meet after Redmon sneaks into the Salemi warehouse, ends up being an amateur composer, and contributes a pulsing synth score which feels like it would be at home in a Nicolas Winding Refn film.

In this regard, the gently cajoling energy the film exudes seems in some ways to almost become its chief point: Manifest indefatigable positivity, and maybe, just maybe, you can bend the world to the change you want to see. The one big exception to all this is Sgarbi, who keeps finding ways to blow Redmon off.

Still, even at a mere 88 minutes, Kim’s Video drags a bit, and could be described as repeatedly yielding to various cul-de-sacs of willful cultural misunderstanding. It’s no sin not to speak a foreign language. But it’s not the best-laid cinematic plan to show up, wing it, and expect answers or insight from people who speak little to no English. Here, a certain tension develops, as the movie settles into a rhythm and tone that could best be characterized as a pleasant tedium.

Given the film’s deeply personal nature, it sounds counterintuitive (and maybe even a bit ridiculous) to suggest, but it feels like Kim’s Video is slightly mis-framed, and would have benefited from the keen eyes of an outside editor (Redmon and Sabin share those duties as well). By making some structural tweaks, more substantively exploring its subject’s heyday, pruning various elements, and perhaps exploring other decisions that Redmon breezes past in connective narration, a richer and more naturally cathartic work would have emerged.

That said, Kim’s Video is still quite interesting—and doubly so as one ponders the value of both outsider art and physical media in the digital age. For cinephiles with an appreciation for stunts and diversions, Redmon and Sabin’s disquisition on cinematic art in the modern age will play like catnip.

Kim’s Video opens in select theaters on April 5.