King Kong goes to war in the Vietnam-themed monster mash Skull Island

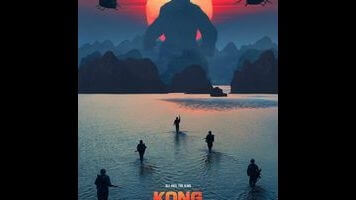

Against a bright orange sun, a giant gorilla towers in silhouette, helicopters buzzing around his head like angry insects. It’s as if that artist who paints monsters onto thrift-store paintings got his hands on the Apocalypse Now poster. Airlift out this most striking and revealing image, however, and Kong: Skull Island would still announce its subtext with all the subtlety of, well, a rampaging ape. This is a movie where choppers drop bombs on acres of green, where soldiers run through the jungle to “Run Through The Jungle,” where one character is named Conrad and another might as well be named Kurtz. Their heart of darkness: a quagmire on Skull Island, circa the end of the war and filmed in faded colors that don’t so much recall the look of the 1976 version as they do footage from Saigon. “This place is hell,” someone solemnly utters. Would Viet Kong have been too on the nose?

Eighty-four years after he first stomped onto screens, the eighth wonder of the world has been cast as a chest-pounding metaphor for one of America’s deadliest boondoggles. He also remains, of course, just a big primate—going apeshit on human invaders, dislocating reptilian jaws, slurping up the tentacles of oversized octopuses like strands of living spaghetti. Ultimately more interested in gorilla warfare than the guerilla kind, Skull Island looks from a distance like a Vietnam polemic with a monster painted onto it. But the opposite is truer. It’s a King Kong movie—a state-of-the-art monster mash, complete with giant bugs and prehistoric menaces and dwindling human numbers. The chief novelty, beyond all the Coppola camouflage, is the absence of a last-act scenery change to Manhattan. Maybe they’re saving the Empire State Building for the sequel. Or maybe this Kong, who could hold Fay Wray’s entire extended family in his palm, is just too big to climb it.

There is a blond beauty for the beast to cradle, but she’s a touch less damsel-in-distress this time: Oscar winner Brie Larson, rocking some ’70s fashions to rival the ones she dons in the upcoming Free Fire, plays a war photographer who smells a scoop, hopping aboard a mysterious expedition to the South Pacific. Getting to the island tends to be the most reliably tedious aspect of any Kong—from the American reboots to the Toho imitations—but Skull Island has a lot of globe-trotting fun assembling its team of expendables, including Tom Hiddleston as the great white hunter, Samuel L. Jackson as a jaded sergeant seething about the ceasefire, and John Goodman as a scientist exploiting the chaos of wartime to fund his voyage. (“Mark my words, there will be never be a more screwed up time in Washington,” Goodman says, in a wink courtesy, one might presume, of Nightcrawler’s Dan Gilroy, one of the script’s three credited authors.)

In some ways, this is a strange blockbuster: cheeky one minute, grave the next, as during a trip down the river—more shades of Coppola—that starts with banter and ends with sudden death from above. The tonal whiplash is also reflected in the movie’s seriocomic variation on the Marlon Brando figure, an American fighter pilot who’s lived in the jungle since World War II, when he crash-landed in Kong’s backyard—an adventure-serial prologue that kicks Skull Island off in style. Some of the character’s shtick, performed by a manic John C. Reilly, wouldn’t feel out of place in Land Of The Lost. Other times, he looks like the movie’s most poignant creation: a POW frozen in time. (Not that he’s literally a prisoner; this is the closest a King Kong movie has come to presenting its natives inoffensively, or at least more as noble primitives than kidnapping boogeymen.)

None of this has any direct relation to the last major Kong movie, the majestic (if overlong) Peter Jackson epic of a dozen years ago. Instead, Skull Island belongs to the same cinematic universe as the recent Godzilla reboot, allowing for a future war of the brand-name Gargantuas. They share more than just a business strategy: Kong, too, productively limits its headliner’s screen time—we never tire of his vast sight—while also playing with scale in inventive ways. Even less qualified in theory for special-effects duty than Gareth Edwards was, Jordan Vogt-Roberts (The Kings Of Summer) proves a similarly quick learner in the field of pitting massive CGI creatures against each other. While the director can’t quite top his first big set piece—the nightmarish encounter between a helicopter fleet and the furry giant they foolishly irritate—he has an affinity for ghoulish sight gags. Skull Island also plays with the system of checks and balances proposed by Godzilla; mean as Kong gets, he’s really around to protect everyone from a race of skull-faced, lizard-tongued subterranean dinosaurs—the undercard competitors before the forthcoming title fight.

Of course, the real monster here is the hubris that fuels wars that can’t be won, embodied by Jackson as a hawk convinced that he can wipe any threat off the map, even one as formidable as an ape the size of a skyscraper. But does the film say anything that 40 years of anti-war pictures haven’t already, or does it just say it louder and with monsters? Apocalyptic though some of its imagery may be, Skull Island ultimately owes less to Coppola than to his most successful New Hollywood buddy, a man who might certainly appreciate such set pieces as the one where a flashing camera lodged in a beastie’s belly warns the survivors of its movements or another where a big-ass spider leaves some poor soul looking like the milk-drinking foster dad in Terminator 2. And while Jackson throws his full authority into the declaration that “This is one war we’re not going to lose,” his most crowd-pleasing line makes the Jurassic Park parallels direct and not just implied. Trying to top that seminal effects movie is a losing battle Hollywood won’t quit fighting any time soon.