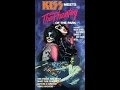

KISS Army AWOL case file #51: KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park

My World Of Flops is Nathan Rabin’s survey of books, television shows, musical releases, or other forms of entertainment that were financial flops, critical failures, or lack a substantial cult following.

KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park resembles a number of misbegotten spin-offs, as it represents the most embarrassing manifestation of a pop-culture touchstone. Like other bastard progeny—The Simpsons’ cash-grab effort The Yellow Album, the non-Beatles movie Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, the Atari E.T. home video game, and the Star Wars Holiday Special—it takes pop-culture monoliths in such unfathomable directions that the creators and fans of the corrupted landmarks try to wish these monstrosities out of existence through sheer force of will. (In the case of Atari’s E.T, the notorious video game was literally buried.) The red-headed step-children of these cultural milestones even call the integrity of their source material into question.

Although KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park is just as infamous as these other efforts, KISS never had much integrity to begin with. The television movie’s notoriety lies not in how it strays from what made KISS great, or at least fun, but rather in how it embodies the comic-book-crazed, monster-movie trash aesthetic of KISS’ Gene Simmons so purely that even he found it obnoxious. If you were to include a scene of Simmons deriding Frehley and Criss to a reporter that he’s also disparaging while receiving oral sex from a mother-daughter groupie team and counting a giant stack of $100 bills, then KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park would be a perfect reflection of Simmons’ sensibility.

The G-rated nature of KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park feels dishonest. These were debauched maniacs out to fuck your girlfriend, snort your cocaine, and crash your car into a brick wall, not kid-friendly do-gooders out to solve mysteries and defeat evildoers through their space magic. Simmons is much less interested in helping people out than in helping himself to other’s people money, something he’s quite gifted at acquiring. He’s less skilled at things like “music” and “being a decent human being.”

So KISS made a vehicle too cheesy and dumb even for a KISS project, which is remarkable when you consider that proud stupidity and cornball excess have long been core components of the band’s brand. In its tackiness, its crass opportunism, its low-budget B-movie drive-in vibe, KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park isn’t remotely off-brand for KISS, which may be why it has accomplished the impossible and proved an embarrassment for a band devoid of shame.

A Hard Day’s Night set the blueprint for rock ’n’ roll movies to follow (with perverse exceptions like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) but KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park diligently follows a much different model: Scooby-Doo. Instead of trying to be John, Paul, George, and Ringo, the gents were trying to be Fred, Daphne, Shaggy, and Velma. It comes about its Scooby-Doo vibe honestly. It is the product (and I do mean “product” in every form) of animation powerhouse Hanna-Barbera, whose tacky, lazily written and animated empire of beloved and non-beloved crap includes stuff like Yogi Bear and the various iterations of Scooby-Doo.

KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park has a Scooby-Doo setting (a struggling amusement park full of animatronic monsters) and a Scooby-Doo villain in Abner Devereaux (Anthony Zerbe), a scientist of the discredited but cinematically fruitful “mad” variety who has devoted his peculiar, prickly genius to creating robotic figures for an amusement park that are frighteningly realistic, more human than human. He believes the park should be a vehicle for his ingenious, wholesome creations rather than a venue for those lizard-tongued louts in KISS, who do not appear to share his love for old-timey barbershop crooning or hyper-patriotic ditties. Too thin-skinned and pure for this vulgar modern world, Abner can’t handle it when a group of cartoon greasers start antagonizing his freakishly realistic robotic ape and accuse the enraged scientist of having an inter-species relationship with his creation. The young hoodlums taunt, “What’s the matter with you and Magilla Gorilla? You got something going?!” (Magilla Gorilla is also a Hanna-Barbera production.)

KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park begins with giant images of KISS juxtaposed over the Magic Mountain theme park where the action takes place. But after the opening credits, KISS disappears for a half hour so that Phantom can focus on what the filmmakers apparently really find fascinating: the conflict between pure science and the harsh demands of commerce as they relate to a struggling amusement park. Abner clashes with his boss and is fired despite his rather impressive ability to simulate life like some manner of contemporary Dr. Victor Frankenstein. For its first act, you could be forgiven for assuming that, despite its title, Phantom is a drama about a brilliant but disillusioned scientist in which an annoying rock band in clown makeup contributes a small cameo.

When Abner loses his job, he sets about enacting revenge on the park and the people he considers responsible for his misfortune: those infidels in KISS. This is where things get needlessly complicated. Like a surprising number of debacles, KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park has the curious quality of being simultaneously stupid yet inexplicably convoluted. In The Phantom Of The Park, KISS is a popular, perpetually touring rock band, but they’re also superheroes with magical powers that have something to do with magical talismans, or something. Paul Stanley (Star Child) can shoot a laser out of the star around his eye and has superhuman hearing abilities. Gene Simmons (The Demon) is a ferocious beast who breathes fire and roars like a lion at random intervals while Ace Frehley (Space Ace) is also able to shoot lasers, as well as teleport. Peter Criss (Cat Man) has the cat-like superpowers of leaping ability and agility.

The gang uses their special powers to solve their Scooby-Doo mystery: a blandly handsome employee of the park has gone missing, alarming his blandly attractive girlfriend. She senses that something has gone wrong and also that Abner may have used his evil genius to turn her boyfriend into an unthinking automaton. This poor woman doesn’t even need to talk to KISS for them to know what’s up. After a stunning performance, they simply look at her, and, when she expresses gratitude for her help, Simmons stiffly intones, “No gratitude need be voiced. Your mind speaks to us!” That line is sadly representative of the dialogue, which gives musicians who can’t act words that even the greatest actors wouldn’t be capable of delivering convincingly.

The KISS-as-superheroes conceit barely makes sense, and the musicians’ powers seem to change to suit the needs of individual scenes. Yet it’s somehow easier to buy these large, strange men as superheroes than it is to buy them as people who might enjoy spending time with each other in a non-professional capacity, so non-existent is their chemistry despite their extraordinary musical success. It is similarly easier to buy Simmons as an out of control robotic rage-monster under the sinister control of Abner than it is to buy him as a human person with actual feelings. The literal-minded nature of the film also leads to KISS squaring off against an actual Frankenstein’s monster in the mad scientist’s creepy lair.

In its climax, of course, Abner’s robotic KISS doubles square off on stage against the real musicians in front of a very confused live audience. Just as Abner replaced four KISS members he didn’t like with four lookalikes under his control, KISS leaders Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons would soon follow his lead and replace the unruly and rebellious Ace Frehley and Peter Criss with an endless series of replacements who could be counted upon to do what they were told to, or be replaced themselves.

KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park brings together everything anyone could ever want—especially if they’re a 10-year-old private in the KISS Army—in a package so unappealing no one wanted it, particularly 10-year-olds who deserve better. The problem wasn’t that KISS made a movie for kids; it’s that they made a movie for children that was too dumb and cheesy for anyone, regardless of age. It foolishly attempts to combine flying, telepathy, famous monsters of the big and little screen, superheroes, rock ’n’ roll, mysteries, roller coasters, mad scientists, commerce, outer space, theatricality, hero worship and a take on the clash between good and evil. It’s equally rooted in the kinds of Marvel comics KISS had just started appearing in and the simple-minded garbage Hanna-Barbera subjected weak-minded children to for decades.

In no small part because it’s a Hanna-Barbera production, KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park presents KISS as a kid’s group that’s all about helping people and the power of music, as opposed to a degenerate assemblage of drugged-up fuck monsters out for your hard-earned cash. But despite the lengths to which KISS have gone to scrub this transcendently cheesy embarrassment from the band’s history, this year saw the release of a movie that didn’t just suggest a Scooby Doo mystery by way of KISS: It was a collaboration between KISS and their old pals Hanna-Barbera, called Scooby Doo And KISS: Rock And Roll Mystery.

I haven’t seen Scooby-Doo And KISS, but judging from its plot description, it sounds an awful lot like KISS Meets The Phantom Of The Park. It might seem perverse for a group to do a project that in its outline sounds almost exactly like its biggest failure. So why did KISS and Hanna-Barbera hook up again following their traumatic initial collaboration? For the same reason KISS first visited that failing amusement park in the Phantom: It has little to do with giving fans what they want, and a whole lot more to do with the enormous amount of money that can be made in the process.

Failure, Fiasco, Or Secret Success: Fiasco