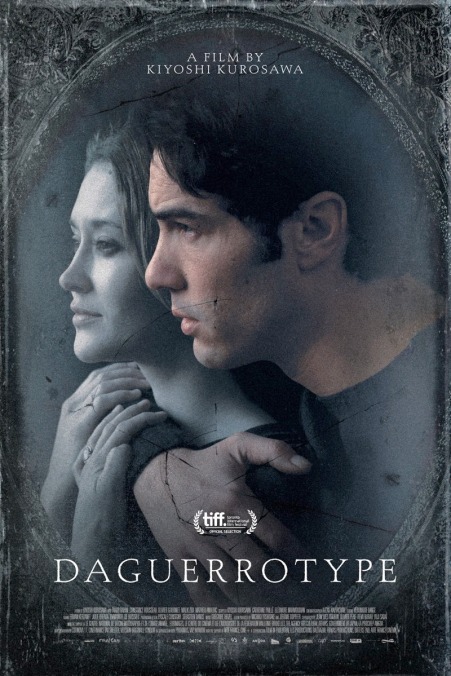

Kiyoshi Kurosawa relocates to France with the underdeveloped Daguerrotype

The Japanese writer-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, a whiz of indistinct scares, has a taste for creepy fairy tales; a modernized take on Charles Perrault’s “Bluebeard” could have made an inspired choice for his first French-language project, but instead he offers up a dullish original in the form of Daguerrotype. (What’s up with the misspelled title?) Here, at a gated property on the outskirts of Paris, a retired fashion photographer creates life-size daguerreotypes of his strange and beautiful daughter, posed for long exposures in a metal armature that splits the difference between art and bondage. Into their kinky world wanders Jean (A Prophet’s Tahar Rahim), an aimless job-seeker from the city. The photographer, Stéphane (Olivier Gourmet), hires the young man as his assistant and teaches him the painstaking, 180-year-old daguerreotype process, which he calls the only true form of photography. Is he referring to the spooky, three-dimensional qualities of the irreproducible, silver-plated daguerreotype image? The rigors of the process, which appeal to the control-freak sadism that often lurks behind art? Or is he just a crank who’s spent too much time huffing mercury vapor fumes in his darkroom?

The mastery of ambiance and visual space that distinguished Cure and Pulse, Kurosawa’s irrational classics of modern horror, is fully evident here; his silent-era expressionist’s sense of psychic architecture quietly reworks the mansion into an endless dim labyrinth of stairwells, doorways, and tight quarters. Perhaps it’s the decrepit, decadent homestead of cinema, full of references to film’s 19th-century French origins and presided over by Stéphane, whose daguerreotypy parodies both auteurist tyranny and celluloid purism. (Kurosawa was an early digital adopter, though few of his post-Bright Future movies have looked as pretty as this film.) And yet Kurosawa seems sympathetic to Stéphane’s Pierre-Menard-ian attempts to re-create the photochemical past; the sequences in which Stéphane and Jean polish and fume the six-foot daguerreotype plates and load them into the camera (it’s about the size of a small bus) are suffused with mystery. There’s also the matter of the daughter, Marie (Constance Rousseau), an unworldly self-taught botanist whose likeness mesmerizes father and assistant alike. Rousseau has nystagmus, a condition that causes her eyes to scan back and forth involuntarily—an apt visual counterpoint for this slow-going story about men consumed by mirages, visionary obsessions, and their own gazes.

But an essential ingredient of Kurosawa’s crepuscular style seems to have been lost in translation: his dream logic. If the filmmaking in Daguerrotype is some of his most confident and romantic, the plotting is some of his least interesting (it, uh, involves real estate) and most literal, possessed by its own backstory. The first hour nods to film noir, fairy tales, and Gothic ghost stories, before a convoluted turn of events turns it into a ludicrously humorless exercise in quasi-psychological suspense; it should go without saying that cut-and-dried psychological motivations have never been this oneiric filmmaker’s strong suit. Unlike Kurosawa’s recent serial killer procedural Creepy, an entertaining and darkly funny film that became less realistic as it came closer to its solution, implying evil as an unsettling force, Daguerrotype is frustratingly easy to rationalize. It’s also about an hour too long; by the time it reaches the end credits, even the spell cast by his eerie direction and handsome widescreen compositions has worn off.