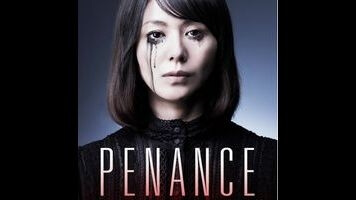

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Penance tells 5 unsettling modern-day fairy tales

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s five-part miniseries, Penance—an episodic, small-screen work that is only being categorized as a movie because it’s being screened in theaters—has a simple, pliable setup, pitched partway between folktale and cold-case procedural. Emili Adachi, daughter of a small-town factory boss, is abducted from her school’s playground and found dead in the nearby gym; four classmates see the killer, but, for mysterious reasons, none of them can remember his face. Emili’s mother, Asako (Kyoko Koizumi) gathers the girls and curses them. “I will never forgive any of you,” she says. “Find the killer. Do whatever you must. Failing that, you must pay a penance that I approve.”

The first four episodes catch up with the girls 15 years later, one by one, while Asako—a kind of evil fairy godmother, often dressed in black—lurks in the background. Each is essentially a stand-alone modern-day morality tale, dosed with a little Charles Perrault and E.T.A. Hoffmann. There is a woman made up to resemble a life-size porcelain doll, a cloud of goose feathers settling over a classroom, a room filled with flowers, and a creaky warehouse loft that brings to mind Bluebeard’s castle—and yet none of them register as out-and-out fantastical, because they’re filtered through the flat, nondescript shot-to-tape aesthetic that is unique to Japanese and Korean TV dramas.

Not that Penance is ugly, per se. Kurosawa—whose international breakthrough, Cure, established him as one of the most original film stylists of his generation—is the master of the creepy static wide shot, and, in many ways, Penance plays like an object lesson in how a graceful sense of spacing and staging within the frame can overcome technical restrictions. Shooting in the outdated, cassette-based HDCAM format, Kurosawa is still able to create images of indelible creepiness, whether it’s a woman’s silhouette reflected in a display of kitchen knives, plastic bags drifting like ghosts in a draft, or the repeated shot of Emili and the killer walking away together, their backs turned to the camera. There are long takes during which dapples of sunlight drift across classroom and hospital walls, and hints of a Hitchcock homage, most noticeably in the Bernard Herrmann-esque sawing and weeping of Yusuke Hayashi’s score.

Penance’s five enigmatic episodes—the four about the witnesses, plus the finale, which deals with the identity of Emili’s killer—don’t present a contiguous narrative so much as different outcomes for the same shared trauma. In a way, each is really a short, small, slow-going feature with its own definitive ending—or, more accurately, its own variation on the same definitive ending. This is hardly the first time Kurosawa has attempted something like this; the bulk of his 1990s output—little-seen in these United States—consisted of eccentric crime movies arranged in diptychs and series, the best-known of which are the back-to-back revenge movies Serpent’s Path and Eyes Of The Spider, which feature the same protagonist and starting point. His work is thick with doubles and repetitions, from the identical murders and coded signals of Cure to the title character in Doppelganger to the musically repeated motifs of Tokyo Sonata.

Each of these five tales—which could just as easily be called movements—concludes violently, with the protagonist left more or less unsatisfied. The overarching theme is the slow, trickling spread of evil; the old familiar story of violence begetting violence, which Kurosawa is able to render in terms that seem mysterious and sub-rational.