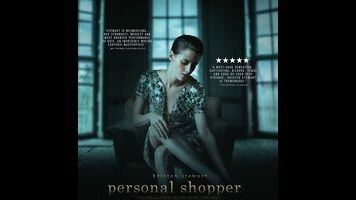

Kristen Stewart browses for ghosts in Olivier Assayas’ unclassifiable Personal Shopper

Haunted-house spookfest, stalking thriller, character study, mood piece: The different sides of Olivier Assayas’ bewildering but compelling Personal Shopper don’t overlap so much as touch one another in passing. Its heroine, the insouciant American expat Maureen Cartwright (Kristen Stewart), makes her living picking pricey clothes on behalf of a celebrity client; she’s also a budding spirit medium trying to make contact with her twin brother, who died of a congenital heart defect that she shares. In a sense, Assayas (Carlos, Irma Vep), one of our most cosmopolitan living directors, has created a chic update to the gothic ghost story. In lieu of a horse-drawn carriage, the opening shot offers a Volvo waiting at the gates of an old manor house on the outskirts of Paris; the classic unsigned letter becomes an interminable series of texts from an unknown number, while the long expository conversation between Maureen and her employer’s lover (Lars Eidinger) might as well have been written for a Victorian drawing room. As in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s less accomplished Daguerreotype (still undistributed in the United States), the commitment to a 19th-century storytelling aesthetic even extends to an unnecessary subplot about real estate.

But the truth is that Personal Shopper’s plot, which dovetails into a murder mystery about two-thirds of the way through, is almost inconsequential. For Assayas, the seemingly opposite milieus of haute couture and spiritualism—one the last word in materialism, the other in immateriality—are equally sensual, transformative, and tempting. The similarities between a forbidden walk-in closet and a creaky mansion possessed by the dead are tenuous, but powerfully suggestive. Assayas films them in nearly the same way, with a prowling camera. He sets out to conjure an eerie conflation of craving and metaphysical yearning, nailed in one early, terrific cut that jumps from Maureen lighting a cigarette to her sitting in the dark, hours later, in anticipation of a sign from beyond. It’s very indulgent, but that’s close to a given in movies about longing, which always seem to locate their themes through a filmmaker’s previously established fascinations. In Assayas’ cases, these include hotels, seasons, 20th-century art, the ins and out of travel (especially airport and trains), and anything involving Stewart, the muse of the film.

More so than his last film, Clouds Of Sils Maria, Personal Shopper is undercut by the French writer-director’s on-the-nose English-language dialogue. This is a bigger issue for the supporting cast than for Stewart, who got one of her finest showcases in Clouds (also playing a celebrity’s personal assistant) and has a way of infecting scripted action with naturalism. Her character is the remnant of a pair; she is in a sense haunting Paris, even though her boyfriend (Ty Olwin, seen only via Skype), apparently some kind of IT contractor, has already moved on to Oman. Although it marks a rare foray into digital spectacle for Assayas—which is to say, the ghosts here aren’t merely implied—Stewart’s performance remains Personal Shopper’s most consistent effect. The gloomy, ominous atmosphere that the movie creates whenever it decides that it is, in fact, a horror film is surprisingly potent, considering many conventions or expectations it otherwise defies. But the bulk rests on Maureen’s tightly drawn shoulders.

Stewart makes the scenes of her character’s day-to-day life seem unrehearsed and intimate, as though the movie were peering in on someone whose thoughts were always someplace else. A lot of it is the magic of casual gesture—things she does with cups of espresso, boarding passes, keys, her iPhone. Of course, she resembles so many other roving millennials. Personal Shopper isn’t always successful; there are spots where it borders on nonsense. It rarely pairs wants with satisfactions, clues with solutions. And whether she is decked out in high-end evening-wear borrowed without permission or confronted with a mutating, translucent ectoplasmic presence, Maureen never appears completely convinced of what she is seeing or experiencing. Perhaps the movie is as much about recasting modern ennui in the deeply evocative terms of the supernatural and irrational as it is about one young woman’s personal and spiritual crisis.