Kristen Stewart shines in the sensitive short story collection Certain Women

Because of their manageable length and tendency to privilege evocative description over intricate plotting, short stories are arguably easier to transport to the screen than novels are. Rather than trying to condense a couple hundred pages into a couple hours, filmmakers can build out from a compact, rock-solid foundation. How many of these adaptations, though, actually capture the spirit of the format—the open-ended mystery and vividness of great short fiction, the sense that you’re being plopped down for a few meaningful minutes into a hyper-specific space? Certain Women comes closer than most. Written and directed by Kelly Reichardt (Meek’s Cutoff, Night Moves), the film assembles several movie stars for a triptych of minor-key Montana character sketches, each based on a story by award-winning author Malie Meloy. Imagine a version of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts that didn’t weave its individual tales into some ensemble tapestry, instead simply offering a few acute approximations of Raymond Carver’s voice. That’s Certain Women.

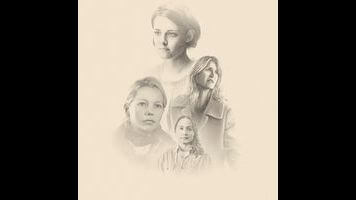

Meloy, the older sister of Decemberists frontman Colin Meloy, has actually earned Carver comparisons for the precision of her language and the ambivalence of her pocket-sized dramas. Reichardt does her best to translate these qualities, finding a properly unvarnished visual correlative to Meloy’s prose and reproducing much of her dialogue. In the first segment, Laura Dern plays a lawyer whose desperate client (Jared Harris) is getting screwed out of his workers’ compensation. In the second segment, Michelle Williams and James Le Gros are parents looking to acquire some sandstone for the house they’re building together. And in the last, longest, and best segment, a lonely ranch hand (Lily Gladstone) develops an infatuation with the commuting lawyer (Kristen Stewart) teaching educational law in her one-horse town.

Moving from her native Oregon to the more mountainous terrain of Montana—captured on the gorgeous grain of 16mm by regular cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt—hasn’t muted the director’s gift for conveying the beauty and despair of America’s quietest corners. And though the omnibus format is a change of pace for Reichardt, Certain Women operates in the same mundane, melancholic register as past films like Old Joy and Wendy And Lucy, both of which were also based on short stories. The source material plays to her interests and strengths, allowing Reichardt to focus almost exclusively on tiny details of character and environment: a man in full native tribal garb standing at the counter of a tacky mall buffet; a single lightbulb on a patchy ceiling, looking as lonely as the woman staring up at it; the way Fuller (Harris) examines a poorly set door, absently demonstrating the job expertise his work-site accident has compromised. To call the film understated would, well, understate it; having previously stripped the outlaw saga, the Western, and the crime thriller of their usual thrills, Reichardt here sinks into stories low on even the potential for traditional conflict. (The one moment of genuine, high-stakes danger is comically downplayed.)

The first two vignettes, pregnant with social discomfort and satisfying in their anticlimax, will appeal chiefly to those who don’t consider compliments like “small” or “unassuming” backhanded. But the standout, the one that makes Certain Women essential viewing, is the closing story: a heartbreaking two-hander about the lopsided relationship a couple of lonesome people forge across a small-town diner booth. Reichardt, in her biggest deviation from Meloy’s text, swaps the gender of the main character, so that it’s now a part-Cheyenne cowgirl softly pining for the out-of-town teacher—a change that gives their quasi-romance an extra uncertainty, at least in deep rural Montana. Mostly, though, the filmmaker just allows two terrific actresses to naturalistically play out this achingly sad scenario. Stewart, in the latest evidence of an immense talent underutilized for years in franchise work, skillfully communicates that nebulous gray area between politely commiserating with a stranger and trying to keep a safe social distance. Even more remarkable is her scene partner, newcomer Lily Gladstone, who delivers a performance of radiant vulnerability—the kind that might be star-making, were it not so generously calibrated to match the everyday proportions of the film containing it.

That last chapter ends on such a perfect note, with such a perfectly devastating final shot, that it’s disappointing when Reichardt opts to chase it with a small series of epilogues, briefly checking back in on the characters of each story. Since inconclusiveness is one of the film’s biggest merits, replacing an ellipsis with a period feels like a mistake. Also unnecessary are the tiny attempts to link the segments, mostly by allowing a character from one to briefly appear in another. Certain Women doesn’t require such connective tissue. It’s cohesive enough in its sustained mood, its overarching discontent, and the gently feminist frustration of seeing its headstrong characters—an attorney whose legal advice is ignored; a houseguest addressed only through her husband; two overworked night owls—rendered invisible by their culture. Like a lot of really strong short story collections, Certain Women is greater than the sum of its parts, even if one of those parts is also significantly greater than the others.