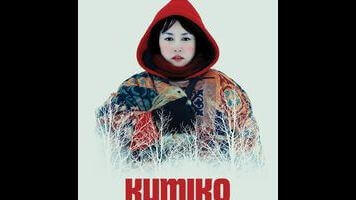

Kumiko The Treasure Hunter dramatizes an urban legend of Fargo fandom

In 2001, a Japanese woman named Takako Konishi was found dead in a Minnesota field. It was a fairly unsensational case of suicide—Konishi was depressed after having lost her job, and had traveled to the U.S. because her married American lover lived in Bismarck—but the media reports somehow got mangled, and an urban legend was born. Supposedly, she had watched the Coen brothers’ Fargo, believed the (false) opening statement that it’s based on a true story, and subsequently died trying to find the briefcase full of money that she’d seen Steve Buscemi’s character bury in the snow. While the story was ludicrous on its face (even if someone were dumb enough to believe the events of a movie happened exactly as portrayed, they’d hardly imagine that the briefcase is still sitting there five years later, after the snow has melted again and again), it captured people’s imaginations. Now, brothers David and Nathan Zellner have made a movie that uses that premise as its starting point, conflating the bizarre legend with the real-life tragedy behind it.

Accordingly, they’ve changed the character’s name and circumstances. Kumiko (Rinko Kikuchi, from Babel and Pacific Rim) doesn’t have an American lover, but she is extremely depressed, mostly because she doesn’t have anybody else, either. Her office job as a barely glorified secretary is so demoralizing that she’s constantly tempted to spit in her boss’ tea, and she appears to have no friends—just an overbearing mother (voice of Yumiko Hioki), who calls her to ask why she isn’t married yet, and a pet bunny named Bunzo. Kumiko’s only solace is her conviction that the Fargo briefcase is waiting for her to dig it up. Before long, she’s disembarking a plane in Minneapolis, though her efforts to get from there to Fargo are hampered by her extremely limited English and—once her former employers cancel the company credit card she stole—her lack of funds. Furthermore, the people she encounters, all of whom want to help her in a general sense, nonetheless keep trying to deter her from her goal. But Kumiko will not be dissuaded.

This is the Zellners’ fifth feature, but it’s the first one that’s getting a significant theatrical release, mostly because their sensibility is far from mainstream. Despite the grabby premise, Kumiko doesn’t really tell a story—it’s a character study of a depressive, its downbeat elements compounded by our knowledge that Kumiko’s one source of hope will lead to disappointment. Nonetheless, the film does have a sense of humor, especially once Kumiko arrives in the U.S. and begins interacting with Midwesterners. In fact, her quest frequently seems to be little more than an excuse for her to stare in befuddlement as strangers say strange things to her. An elderly woman (Shirley Venard) who sees her walking in the cold brings her home to warm up, then shoves a copy of James Clavell’s Shogun into her hands while delivering a monologue about the superiority of paperbacks to hardcover books. (Brushing dust off the cover, she casually notes that “it’s mostly just dead skin.”) Director David Zellner turns up later on as a friendly cop who tries to explain that Fargo is just a movie, but who also feels compelled to point out that a statue of Paul Bunyan’s ox, Babe (not the one seen in Fargo), used to be anatomically correct before somebody shot off its privates.

In its broad strokes, Kumiko The Treasure Hunter bears some similarity to Paolo Sorrentino’s This Must Be The Place, which starred Sean Penn in a wildly atypical role as an aging goth rocker. Both films feature a protagonist who travels to the U.S., embarks upon a ludicrous mission (Penn’s character seeks out the Nazi who had tormented his late father at Auschwitz), and has offbeat encounters with colorful folks in the American heartland. But whereas Sorrentino’s story was about personal growth, Kumiko waffles about whether it wants to embrace despair or redemption, and ends up awkwardly attempting to do both. It’s not even clear which parts of the movie are real and which aren’t. The final scene is unmistakably coded as fantasy, but the opening scene—in which Kumiko, consulting a treasure map, finds a decrepit VHS copy of Fargo buried in a cave—seems equally absurd, even though that same barely watchable tape (eventually replaced by a DVD) appears in Kumiko’s ordinary, mundane life. Ultimately, despite Kikuchi’s expressively dour performance and David Zellner’s formal invention (he gets great mileage out of stopping the camera during a tracking shot to let Kumiko exit at frame right, then having her return), Kumiko feels like a collection of amusing and/or depressing riffs stitched together within a context that barely matters.