Kurt Cobain’s manager remembers him, fondly, 25 years later

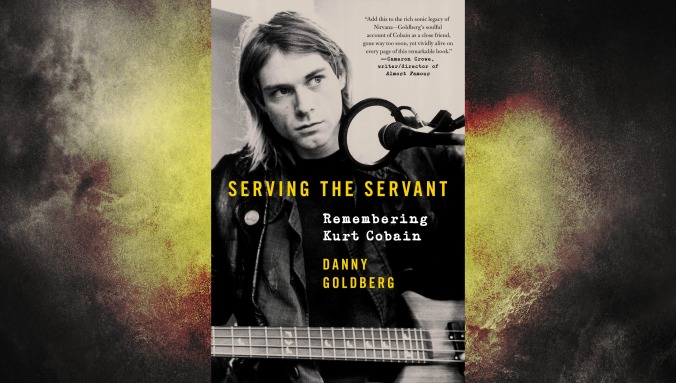

Danny Goldberg knew Kurt Cobain for only the final few years of Cobain’s short life, but as Nirvana’s manager—and something of a father figure—Goldberg had a rare vantage point from which to experience Cobain’s rapid ascent and tragically blunt end. So, by necessity, Goldberg’s Serving The Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain blurs the line between biography and memoir. In fact, those who’ve read Goldberg’s 2008 memoir, Bumping Into Geniuses, will recognize many of the stories he conveys here, though they’ve been expanded from one chapter into 17. In this book, he manages to both give Cobain the credit he deserves for a seismic pop culture shift and to portray him as a regular human being.

For the things Goldberg didn’t personally experience, he relies on new conversations and other sources: He casually mentions getting in touch with Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love, as well as Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic, to fill in the gaps of Nirvana’s early years. That part of the book is relatively well-trod territory, considering how much has been written about the band over the years. There’s Michael Azerrad’s biography Come As You Are, published before Cobain’s death. And there’s Charles Cross’ exhausting but some would say factually overreaching Heavier Than Heaven, which was criticized for speculating about Cobain’s final days. The facts of the Nirvana story have been told and re-told.

Goldberg’s version, though it lacks much in the way of new information, at least approaches its subject from a more earth-bound place. Sure, he praises Cobain’s genius in some breathless passages, but mostly he’s interested in telling the story of the person he knew: The hero worship is present, but it’s tempered by insight into Cobain’s personality that few people were privy to. Cobain, according to Goldberg, wasn’t nearly as opposed to corporate entities as he wanted his more strident, punk-leaning fans to believe. Instead, Cobain cultivated a strong relationship with MTV—particularly a young employee named Erin Finnerty—in order to get maximum exposure. He complained to Goldberg at one point that MTV was playing Pearl Jam videos three times for every one time they spun his. “Kurt kept telling everybody that he had only wanted Nirvana to be as big as the Pixies,” writes Goldberg. “I’m almost certain that he was being disingenuous and that he had been thinking about how to react to success with the same intensity that he had brought to musical rehearsals.”

This is partly a function of Goldberg wanting to see in Cobain what he saw in himself: business savvy. He admits as much when he claims not to have been as aware of Cobain’s drug use as others in their inner circle were, focusing instead on the intricacies of recording and promotion. Still, Goldberg was close enough to the family—he also ended up managing Hole, Love’s band—that he was there for the various interventions attempted on the couple over the years. When Love learned she was pregnant, it was Goldberg and others who guided her to good doctors and helped school her on the dangers of drug use to the baby; Frances Bean would be born in the midst of Nirvana’s superstardom in 1992. And though he admits to viewing his memories through rose-colored glasses, Goldberg doesn’t let Cobain off the hook completely. At one point, he refers to Cobain as exuding “an odious junkie smugness.”

Goldberg also thoroughly recounts the couple’s battle with Vanity Fair, specifically writer Lynn Hirschberg. Her piece, “Strange Love: The Story Of Kurt Cobain And Courtney Love” painted the couple as more or less hopeless heroin addicts who’d almost certainly be unfit parents. Its power was more than rumor mongering: A hospital worker sent the article to Los Angeles Social Services, which led to an investigation. (The article still reverberates: Frances Bean told Goldberg that someone referred to her as a “crack baby” in her teens.) Goldberg helped usher the couple through that situation, as well as a more comical feud with Axl Rose—details of which are far more abundant in this book than has been previously published.

He’s also not shy about sharing financial details: Cobain at one point asks Goldberg how much money he’d make if In Utero—the “difficult” follow-up to the smash Nevermind—didn’t sell very well, and if the band didn’t tour much. Goldberg replies—and publishes—that Cobain would still take home more than $2 million for the year. Unfortunately, as Goldberg eventually realizes, that much cash can be deadly to someone with a drug addiction. In March of 1994, Cobain overdosed and went into a coma; Goldberg foolishly hoped it might be a wake-up call. By early April, Cobain was dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Serving The Servant arrives 25 years later, almost to the day. Goldberg spoke at Cobain’s funeral, and was mocked by naysayers for treating him too reverently—apparently pouring your heart out isn’t punk.

The prose is mostly simple and conversational in Serving The Servant (and the less said about that dumb title, including its explanation, the better), but that’s mitigated by the fact that Goldberg brings some new perspective to Cobain’s story. His subject was complicated and sometimes selfish, though also kind and earnest. Goldberg clearly loved Cobain, and he humanizes him with the kind of small stories that wouldn’t necessarily make sense for a more sweeping biography, like the fact that Cobain cherished The Chipmunks Sing The Beatles so much that he owned four copies. And though Goldberg does put Cobain’s musical contributions on a well-earned pedestal, he also shows the young man—just 27 when he died—as mortal, in ways both good and bad. He knew Cobain intimately, but admits, too, that “Sometimes I felt as close to him as a brother and other times he seemed a galaxy removed, barely perceptible.” Goldberg conveys that split nicely—and, perhaps more importantly, humanely—in his telling of the Cobain story.