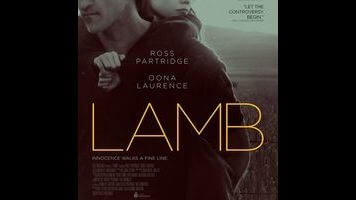

Lamb puts an odd, moody spin on a child abduction scenario

Oona Laurence has been acting in movies, on TV, and on the stage since she was in single digits, even winning a Tony at age 10 for playing the title role in the musical Matilda. But she has a naturalness on camera that’s rare for any actor—let alone for one who’s essentially grown up in the business. Laurence has been memorable in small parts, in films like I Smile Back and Southpaw, and in writer-director Ross Partridge’s Lamb, she easily handles a difficult role, capturing the intelligence and immaturity of a young girl who impulsively sets off on an adventure and then realizes she’s strayed way too far from home. Throughout Lamb, Laurence makes sure that every one of the character’s bad choices makes sense. That’s what makes the movie so sad.

Based on a Bonnie Nadzam novel, Lamb has Laurence playing Tommie, an 11-year-old who spends more time loitering around her low-rent Chicago neighborhood than she does in her apartment with her lackadaisical mom (Lindsay Pulsipher) and her mom’s snippy live-in boyfriend (Scoot McNairy). Then one day she walks up and tries to bum a cigarette off David Lamb (played by Partridge), a depressed 47-year-old who tries to teach her a lesson by dragging her to his car, warning her, “I could be taking you somewhere to kill you right now.” Once he realizes that neither Tommie nor her folks seem too worried about what a random stranger might do, David decides she needs a mentor, to help her appreciate the preciousness of her life. After a few more meetings, David asks her to join him on a cross-country drive out to his ranch property, and she agrees—even though he warns her that to some eyes, what he’s doing will look like kidnapping.

Which it should… because it is kidnapping. What’s remarkable about Lamb is that Partridge doesn’t pretend that what David’s doing isn’t creepy—even though it’s also clear that he’s no pervert, and that he has the best intentions. David takes great pains to make sure that Tommie has all the privacy she needs, and he tells her at the start of their trip that if she ever feels too uncomfortable, he’ll put her on a bus or a plane and send her back. But he also hides her when his girlfriend Linny (Jess Weixler) arrives at the ranch unexpectedly. And when Tommie says after a few days that she’d like to call her mother and tell her she’s okay, David persuades her that the call would cause too much trouble. Partridge frames shots and stages scenes so that there are often cars zipping by in the background or curious strangers walking past, to remind the viewer of his protagonist’s persistent paranoia—because even David knows that he wouldn’t be able to justify his actions if asked.

The big question that Lamb never satisfactorily answers is where this strange, somewhat disturbing relationship would be headed, if allowed to continue on past the closing credits. David never gets pressed on what he’s doing—not even by Linny when she finally finds Tommie. Instead, the film proceeds calmly through the aimless days of an unrelated middle-aged man and preteen girl, who share life experiences in America’s wide-open spaces. Though it’s frequently tense, Lamb isn’t a suspense picture, and it ends before any legal or social ramifications redirect the story into something very different. Given the way the movie plays out, it’d be easy to argue that Partridge is framing child abduction as a beautiful experience for everyone involved.

But look past the implications of what David does (and whether Lamb ultimately approves of it), and what emerges is a powerful study of a desperately lonely man, and of the girl who becomes the sounding board for his ideas about how to live a fulfilling life. David’s living out a fantasy, but not a sexual one. He’s playing out a scenario where he has a daughter to shape and guide, and is seeing if that’ll give his existence some meaning. And Tommie goes along because she likes to think of herself as the kind of independent kid who doesn’t shy away from new experiences.

What keeps Lamb from being too off-puttingly idyllic is Laurence’s performance, which is never overly mature or sunny. Her Tommie recognizes early on that something’s not right with David, or with his “vacation.” But she also knows that she doesn’t have anything waiting for her back in her old life, and to some extent she feels obliged to help this stranger through whatever mid-life crisis he’s enduring. Both of these people are lost, each in their own way. They don’t belong together, and they don’t fit in where they’re supposed to. So in Lamb, these characters indulge in a fiction for as long as they can. And the actors playing them make their situation feel so plausibly real that at times the movie—and the audience—aches with them.