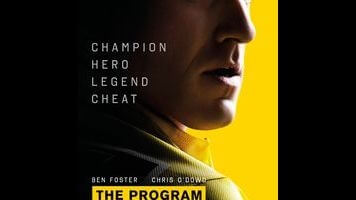

Lance Armstrong is boldly unsympathetic in the otherwise rote The Program

Few biopics are so relentlessly hostile toward their subject as The Program is toward Lance Armstrong. Brilliantly played by Ben Foster as an opaque wall of arrogance and entitlement, Armstrong has no inner life to speak of in this film—no dreams beyond winning the Tour De France, no remorse when he’s finally caught after years of cheating via steroids and blood doping. As a young man in the ’90s, he’s nakedly ambitious and little else; later, when the rumors start flying, he spends his time methodically practicing his lies in the mirror and casually intimidating anyone who dares to challenge those lies. It’s a bold, remote, practically inhuman performance, which gets hilariously underlined at one point when Armstrong mentions that the supremely likable Matt Damon is in talks to play him (in another movie that never got made). There is nothing remotely likable, or even relatable, about Lance Armstrong in The Program. He’s just an ass-covering asshole, which is the sole interesting aspect of an otherwise pedestrian Wiki-history.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.