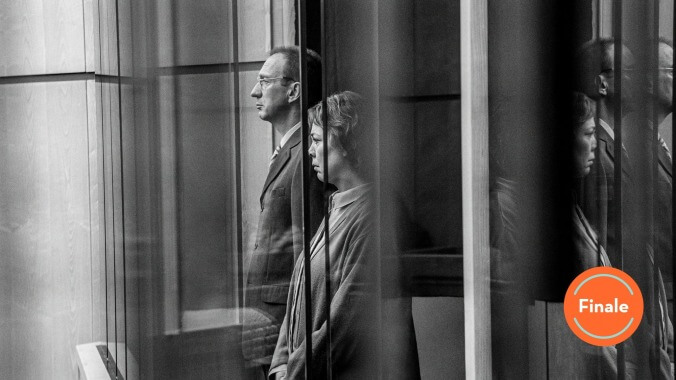

David Thewlis and Olivia Colman star in Landscapers Photo: Stefania Rosini/HBO

In the finale of Landscapers, Olivia Colman’s Susan and David Thewlis’ Chris Edwards stand trial for the murder of her parents, with their desperate union at its most frayed. After the police investigation had closed, this final episode spends half its time on their trial and the other half on its grandest delusion yet: a full-scale gunslinging Western epic in the style of Susan’s most treasured films. The Edwards have reverted into outright fantasy, recontextualizing their version of the crime in what looks like an actual movie. It’s a pure Cinemascope vision rather than a perversion of the cinematic styles like what we have seen in previous episodes, reimagining their flight and capture with all of the players involved making an appearance.

The suggestion of this jarringly fully realized spectacle is that the real world is now entirely shut out from their fantasies and the Edwards have completely divorced from reality in order to mentally survive. The episode’s opening is a series third wall-breaking, Dogme-style hard realism shots of the set, camera, wigs and the like, all shot grimly before this fantasy bluntly arrives; the real world is too harsh to linger in for much time at all. They’re lost, to themselves and (more importantly) to each other.

Susan is somewhat ambivalent to her captivity, lamenting in a letter to Chris that we hear in voice over. “I never cared about being shut out from the real world because I never felt like I was allowed to arrive here in the first place,” she confesses, “I’m not here anyway, am I? So… what’s the difference between here and somewhere else in my own head?” Her world is now presented in black and white, underlining the shades of grey in her case regarding the truth while also highlighting her dissociation. She’s so removed from existing that even her non-daydreaming moments are like she’s living a movie.

But she also acknowledges that Chris’ experience of the world became entangled in hers, that he sacrificed something of himself to care for her. On the stand, Chris attempts to describe how he forfeited his gun ownership due to the effort required to maintain certification, but really revealing her codependency. “I made a choice to marry Susan because I loved her. Since then, I’ve been living Susan’s life with her. My life… wasn’t important anymore,” he says, a loaded statement. As Chris tells it, he has been a passive participant to the fantasy they have constructed, all for his unconditional love for Susan.

When Susan testifies, she gets hung up on the details of her previous testimony. She adds the purchase of air fresheners to her testimony, a convenient previous omission after forensic testimony described the kind of stench the Wycherlys would have left in the week Susan says she took to bury their bodies. More damning, the casings she had described picking up on the crime scene couldn’t have possibly been discharged by the kind of gun used in the crime. Her confusion causes her to crumble, with Colman again proving to be a font of vulnerability able to dive into the most isolated of human conditions. “I’m not fragile, I’m broken. So you can’t hurt me,” she declares, only partly in defiance.

No matter what the truth is in the crime, this statement seems plainly true in Colman’s painful dejection. In finding herself unlovable, she fears that Chris could easily abandon her, and that the fateful call to his stepmother was Chris’ first step in separating himself from their dissociative place in the world. Rather than tidily wrapping up the case of the Edwards’, Landscapers is revealing one of its central questions: how much of the fantasy belongs to Chris, and has he submitted or participated? How much of loving someone is creating your own version of the world, of the truth, of your way of surviving, together? As Chris put it, loving Susan as such was a choice; what’s left for Landscapers to reveal is whether he can or will continue to make that choice.

To the court and surely to many at home, Susan’s compounding fictions are becoming inescapable. But in private, she confesses to Douglas (Dipo Ola) perhaps her most obvious lie: that the Depardieu letters were entirely her tenderly crafted creation. By now, it’s clear to the audience that this has been all Susan, but the lack of consequence the forgeries have proven in the case reflects how little consideration is given to their dysfunctional (or as Chris might put it, “fragile”) bond. The full extent of their sad, shattered humanity is hiding in plain sight.

As the western plays out in Susan’s mind, this fantasy also serves as a reflection of what happens in true crime media with operatic gravity. Their story is ultimately an insignificant one that played out in lower income suburban homes with no impact to the outside world, but this cinematic mounting of it creates a sensationalized sense of scale and intrigue. Their actions are turned into mass entertainment fodder, with the psychological stakes turned into little more than cliffhanger set pieces. It plays both as Susan’s coping imagination and as a separate fictionalized take, the kind of packaged story meant to thrill and shock (often with its own perspective or agenda) that the series has been metatextually critiqued all along.

Landscapers knows it isn’t exempt from that critique, either. You could take it to task for its sympathetic vantage on the Edwards, and of course some have. The series title itself is a pseudo-joke about the crime, or at least a jesting gesture toward the burial part of it. Though the series tries to find the humanity of their circumstance, it is still presenting a version of the Edwards’ for its own thematic aim, so you would be fair to claim its tactics also have a dehumanizing aspect. But just as it empathized with the Edwards while increasingly revealing the case against them as one difficult to argue against, the series has been more interested in how you look at things than what you ultimately think is true.

And what is ultimately true for Susan and Chris is that both were at the driver’s seat of their relationship. Chris finally responds to Susan’s letters, telling her that their relationship wasn’t an escape from the real world, but the thing that made the world come alive. He signs off the letter as Gerard Depardieu, both continuing the delusion and admitting that he willfully perpetuated it himself. He continues to choose Susan, however they may continue to exist together in their imprisoned real world or their imagined one. The traditional western fantasy ends with Chris shedding his costuming, and Susan steps into a new one, still with cameras rolling and orchestra swelling, but finally with themselves as they are. They ride into the distance.

Little actually happens in this closer to Landscapers, but it leaves us with more complex questions to wrestle with than you might initially anticipate. What director Will Sharpe and his writing partner Ed Sinclair have created with Landscapers is a despairing portrait of fact and fiction within a marriage, capable of functioning on multiple levels at a time while finding layers of truth in the unreal. As a show that examines our relationship with true crime as a form of entertainment, it has been thoughtful without being didactic; as a darker piece about the nature of choice and necessity in love, it has offered thorny depth alongside two devastating performances from Colman and Thewlis.

Stray observations

- I Hate Suzie’s brilliant Leila Farzad plays the prosecuting attorney. I was promised a second season of I Hate Suzie. Where is my second season of I Hate Suzie?

- The closing scene for DCs Emma and Paul at first seems like filler or comic relief, but there is something to how their ability to continue about their lives reflects the digestibility of true crime. Also, on a smaller scale, their relationship suggests a different kind of companionship still reliant on what they provide for one another.

- Part of the Depardieu ruse was upheld because Susan had a franking machine. I ask you: who owns a franking machine?!

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.