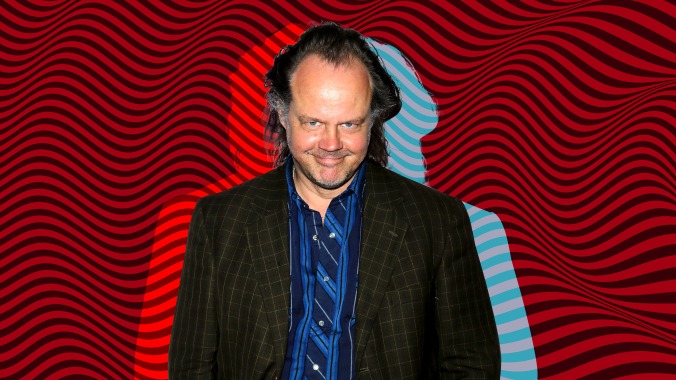

Larry Fessenden on Frankenstein, art, and Universal's Dark Universe: "They don't understand horror"

Larry Fessenden’s name is pretty much inextricable from independent horror cinema at this point. Over the course of the past few decades, he’s become not just an omnipresent indie character actor (turning up in everything from You’re Next to Session 9 to Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out The Dead), but through his company, Glass Eye Pix, he’s helped to bring countless ambitious low-budget films to to life—mostly horror (and what a resume: The House Of The Devil, Darling, Stake Land, to name a few), but also some bold drama and oddball fare (Wendy And Lucy, The Comedy). He’s also dipped into the world of video games, winning a BAFTA award for writing the hit survival-horror game Until Dawn. And through it all, he’s maintained a fairly consistent pace of writing, editing, and directing his own films at the slow but steady rate of one every five years or so. His latest, Depraved, (which had its world premiere last night at the What The Fest?! film festival in New York) is a modern reworking of Frankenstein set in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn.

When we caught up with Fessenden, what began as a discussion of his latest film turned into a fascinating and freewheeling look at the current state of indie cinema, the durability of horror, and why there’s no justification for being an asshole in the pursuit of great art.

AVC: Even though it’s a retelling of the Frankenstein story, Depraved feels like it’s grappling with the ideas and themes you’ve been dealing with throughout your entire career. Have you always wanted to take a crack at Frankenstein in the back of your head, or was the genesis of this film more recent than that?

Larry Fessenden: Well actually, the truth is it’s quite an old project. I say that I have a draft where I wrote a one-page synopsis from 2003. But it does fall into my usual themes of really trying to re-imagine the great horror movies I loved as a kid in a contemporary setting. So I think it’s always been a part of me. I didn’t re-read the book; I just know the book, and I certainly know all the movies. Especially the old Karloff movies, the sort of pathos—there’s something about the story that speaks to me. You’re both afraid of the monster as an objective thing in the night, and you also feel for the monster. So really, it just becomes a personal account of being an individual in this society, and confounded and confused. I think it’s very intuitive to me. But I don’t want to just tell a coming-of-age story. I want to have something fun in there, like the abstraction of monsters and all of the implications there.

AVC: That’s what sort of stood out. Even going back to No Telling [Fessenden’s first feature horror film from 1991—Ed.], you’ve always been interested in these questions of the uses and abuses of science. Is there something specifically about those sorts of thorny philosophical issues that drew you back into using the Frankenstein story as a way to talk about them?

LF: For better or worse, I just can’t help but engage with the big questions. How do we run our society? What are the choices? It’s funny, people think my films are polemic or that they’re preachy about environmentalism, but I just can’t see the world in any other way but to try to figure out, “How could this work? How could we get along?” It’s on a very personal level. “Why doesn’t my girlfriend like me?” All the way up to, “Why do we have such abrasive racism,” and all of these things. It’s never been an external thing for me. It’s very personal, to try to grapple with these philosophical questions.

AVC: It’s funny that people have dinged you for being preachy, because your focus and your interest is always on the psyches and relationships of the people who would involve themselves in such work. Is that what captures your imagination in the original Frankenstein? Or is that more the angle you feel you can bring to these kinds of questions?

LF: Well, I think it’s both. It’s why the story speaks to me. As I say, I relate to the monster as an outsider; he’s bewildered by life. And don’t we all feel that, ultimately? At the same time, one thing I grapple with in Depraved is the dilemma of science solving our problems, physically making us live longer. One thing is, the soldiers that come back from Iraq now, they actually are kept alive, but they have these terrible, traumatic head injuries. Is that really life? I’m not making a judgment whether they should live or die, but there’s an ability for science to get us to a certain place, technology and all of that. And yet we will have to make amends of our mental, spiritual life. And that’s sort of tossed aside.

So that I find really interesting, and that’s why the Frankenstein story is so rich. At one point, the guy says, “You can’t solve all the problems with kindness. Sometimes you need technology.” That’s such a perfect dilemma, because he can create this monster, but he doesn’t know how to parent it. These are just the contradictions of life and I find them so interesting. And they are in these old stories, you know.

AVC: There’s almost a Talented Mr. Ripley quality to these characters. The whole, “No one thinks they’re a bad person, no matter what they’ve done or what they’re doing.” There’s just that disconnect between what they can do and what they’re able to do. The humanism is what I feel was of interest to you.

LF: Dude, you’re singing my song. [Laughs.] That is my point. As an actor, I always say, “When you play a villain, you don’t play him like he’s bad. He absolutely thinks he’s doing the right thing.” Think of Heath Ledger’s Joker. Such a beautiful portrait of insanity, depraved insanity. But he obviously thinks everything’s ducky. I really wanted to bring that to the character of Polidori, that Josh Leonard played. He’s horribly villainous, they talk casually about raising the prices on pharmaceuticals, like that villain in real life [Martin Shkreli] who’s much more depraved than my character. Almost to a fault, I have too much humanity in my characters. Maybe that’s because I wrote it before the current political climate, where just fucking outright disgrace is considered completely normal.

Anyway, whatever, I’m sentimental, so I still have my characters have human emotion. But I love how sad Polidori is. He’s obviously the villain. That’s the place where I stray from the original structure, because the doctor isn’t the villain or the madman, he’s sort of a victim of circumstances and PTSD, and he was tossed aside by society. Even the other guys’ motivations are so petty. They’re saying, “Well, my father didn’t love me.” “I was there in the room, I helped you!” I really feel that human interaction comes down to this little sad pettiness, and that’s what I like to show, the details of the psychology.

AVC: It’s funny that you mentioned the way in which you relate to the monster. The film travels from one of the world’s great art museums to a strip club, and that blending of what we traditionally consider high-brow and low-brow culture felt almost like an exploration of your own art and career, where you’ve done just that. Did parts of that sort of take on an autobiographical vibe for you at times?

LF: I really appreciate the question. Yes, I feel like… all of us are so… there’s such a richness of influence in our lives and our upbringing. I have all the books and the puzzles and the sort of things that jumpstart the mind. And there’s this sort of other lofty notion of great art and museums, and they’re rarified. But then there’s just the physical impetus that you’ll find in a strip club, those impulses. So it is, like, what makes a character of a human being in our society? All of that sounds lofty, but it’s very visceral, to just show it. It’s funny, there’s a moment when the monster looks at a painting of Christ, and he’s actually drawn in. And Polidori is sort of contemptuous and doesn’t even comment on it. There’s some yearning in the human animal to see life through that religious thing, but then you have a pretty good time at the strip club, too. There’s something there, I don’t know what it is. But yeah, that’s the idea.

AVC: It’s interesting, because it’s not just grappling with that seeming disjunction between high and low, but also these ideas of the value of the old versus the new, as well. Both aesthetically and narratively.

LF: Yeah, and where do we make the choices of what we keep and what we discard? I showed Jackson Pollack, and I don’t actually personally believe this, but Polidori says, “Art shat the bed.” Or, “This is where narcissism took over.” I do feel that human narcissism is a corrupting, toxic element, and the whole point is that you try to aspire to higher ideals. Anyway, the weird thing about the movie—I was trying to write about it, just for the fucking press kit, and it’s not pretentious, it’s just to say that it is about all these things. I used to joke on the set, I’d say, “Oh don’t worry, we can show the wire, because this movie’s about electricity among everything else.” And everyone would laugh and roll their eyes. But my point is I really wanted to try to tell a very succinct story in which everything was sort of accounted for, the whole history of humanity. I used to say that on set. It’s unbearably pretentious, except that I don’t mean it that way. It’s just that you’re filled like a vessel with all this sort of stuff, and you have to sort through it in order to be a moral person. And of course, I suggest in the end that it’s not possible, that everyone’s an asshole. [Laughs.] Sad little tale.

AVC: The last time we interviewed you was almost exactly 10 years ago, when I Sell the Dead was coming out. Are you surprised by where your career has taken you? Or does this feel like the natural progression of where you were at that time?

LF: Well, I don’t know. John Lennon, or you can quote whoever, “Life is what happens to you when you’re making other plans.” When I was a kid, I thought I’d be Spielberg, because I loved Jaws. But I also never quite played the game. You actually wake up one day, and you go, “I’ve done it exactly true to myself.” It’s very frustrating, though, because I see exciting, big movies, I see them fuck up the Universal pictures, whatever that’s called—the Dark Universe—they fucked that up. They don’t understand horror. So in that regard, I’m extremely bitter that I’m just where I am. In case you need to know. [Laughs.] That’s the headline: “Fessenden’s bitter!” But the reality is, I also accept that my movies are peculiar. I’d rather make them as best I can, try to make the best possible movie along the lines of what I see than be chasing a dream that’s really just a dream to be at the Oscars. So it’s complex. I don’t profess to be delighted to have to spend 10 years raising the money to make a Frankenstein movie; that’s ridiculous. But we’ve made a lot of cool movies.

AVC: I do think there’s a philosophical element to the fact that oftentimes great horror comes from the margins. It comes from the underground, these weird, dirty, strange places that aren’t the middle of the road.

LF: Dude, you are, once again, singing my song. This is the point. Horror is supposed to be alternative. It’s supposed to make you really question society, quite honestly. It’s supposed to shock you out of a certain complacency. As you well can imagine, all of the profound political implications of horror throughout the century, from Night of the Living Dead to Godzilla, they’re all responding to real problems, real world problems. When you just turn it into—all due respect to Jason Blum—those haunted house movies, you’re not really using the genre as robustly as you could. It should be alternative. I always say, it’s right there next to porn in the video section. Eh, we don’t have video sections. [Laughs.]

AVC: Has there been a shift, maybe even in your own thinking, about how horror is changing to express new thinking or new ideas? Because some of the projects you’ve been involved with lately, either as an actor or producer—I’m thinking here of Like Me or Darling or even Until Dawn—reflect a very different world and even a different public understanding of horror than existed 10 or 15 years ago.

LF: Well, horror was really the perennial, and it did manage to make money. The cliché is that you can make a cheap horror film because you don’t need movie stars, because the genre itself is the star. So that’s all wonderful. And it’s a playground for young filmmakers to sort of learn their craft, Coppola and so on made early horror films. But at the same time, I do think the genre has grown up. And now you really can see a blend—I’m thinking of It Follows or The Babadook—between an indie sensibility and then something very dark.

Remember, horror is really just speaking of dark things, probably with a fantasy element, or some other layering of artistry, which is why I like it. The genre’s grown up. I’m not really here to complain about that in particular. I feel great about the movies we’ve made. I don’t know if Like Me is really a horror movie, except you could say it depicts a society gone fucking wrong. But the movies we make are challenging, unexpected, off-kilter, and that’s really where cinema can still be vital. In all due respect to the superhero movies, you kind of know what you’re getting into. You know, they might have a little tiny sheen of something forward-thinking when they have people of color or women starring in them and all those things, but those are just sort of cultural shifts. Are they really challenging you? I would say not quite.

AVC: With Glass Eye producing so many of the more noteworthy unconventional and challenging movies of the past decade or so, what would you say has most surprised you about the work you’ve done in that time?

LF: Just how little traction I get. A tiny pocket of very deep love, and I’m extremely respectful and grateful for the people that know my work. But there’s a whole bigger game that I’m not very good at, to sort of get your foothold. Listen, all of this is for the sake of wanting to do your next project, do your work, do better, bring other people up with you. I sort of have done that by getting some young filmmakers their first movie. Some of them I’ve managed to push out the door, like [Jim] Mickel and Ti West, even Kelly Reichardt was my early pal, and we did stuff together. So that’s also a mission. I’ve got to say, you don’t always do exactly what you thought you wanted to do, but I feel like I’m still working that mission.

AVC: It seems like you’ve also discovered some unexpected angles to your own work. For example, I can’t imagine you’d have guessed 10 years ago that you’d have this project four seasons and running that’s essentially resurrected the radio play, complete with live performances at Lincoln Center. [Tales From Beyond The Pale—Ed.]

LF: Oh, yeah, dude. It’s such a pleasure. But you know what? That’s something we can do without the approval of others. We simply do good work and some people care, and they come. By the way, we’re going to put that finally into the podcast format, for the kids. The kids can’t seem to find our CD box sets. We’re losing them. [affected voice] I have some 8-track cassettes here for the little ones. [Laughs.] So yeah, I do that with Glenn McQuaid, and we’re just wildly proud of it. It feels like, while you guys are all raising money, we’re going to show you how this is done and take you in an incredibly immersive world of audio plays that are of every conceivable tone. That’s the thing about horror, it’s a huge umbrella under which there’s comedy, period pieces, grave robbers, toxic waste, giant monsters. Everything wonderful. I’ve made more monster movies on the radio. I assure you, it’s very cheap. All you need is like three growl sounds. [Laughs.]

AVC: That’s what is so great about Tales from Beyond the Pale, it cuts to the heart of the appeal of storytelling. Have you discovered a renewed love for the purity of old-school storytelling, stripped of any visual aspect, through doing that?

LF: Oh yeah. But I do believe some of them are very forward-thinking in terms of structure. That’s the thing—you truly get to experiment in a format that’s not going to break the bank, and if it doesn’t work, so be it. Although, I have to say, they’re all just so refreshingly different. One of the things Glenn and I loved to do is to say, “well, this one, we’re not having dialogue. We’re going to have only sound effects.” And we’ve almost pulled it off. I did one in which this house was expanding and collapsing, and the guys were inside going, “Whoa! What’s happening?” It’s all just sound effects. It’s so fun to imagine you can transport someone through sound. I always like to say this about my bad special effects: The audience has to help. They have to participate in building the monster. Wendigo[’s monster] is famously poor as well, just some awkward effects there. But I believe that the audience has to go along with it. When I grew up, you could see the zippers on half the monsters.

AVC: That was always the thing—whenever somebody says, “Oh, that looks so fake,” or “you can see the plastic,” it seems like their problem isn’t that they can see the seams, the problem is that they’re refusing to surrender to the story, they’re refusing to engage in that world.

LF: That is a profound truth. And actually, I feel like the nightmare is, that’s what happened to the culture now. It’s such a gotcha, told-you-so society with Twitter. “Oh, I saw this!” You’re like, oh my god—what was the intention? Maybe they didn’t have the budget. Do you still see the ideas? Or are you just trying to “gotcha”? It’s a very entitled culture that we’re in, all sides. Not just the well-to-do city kids. Everybody’s sort of sitting, judging from their lofty place from their silly little Twitter-sphere. It’s terrible. And the whole world’s collapsing around us. The arrogance of humanity!

AVC: But maybe that’s part of it—when people see everything collapsing around them, it’s understandable to say, “Well, what can helpless little me do? I guess I’ll just sit here and make some jokes on Twitter.”

LF: Well, I understand, but I don’t buy it. I always say, when you’re in the lifeboat, and the hole’s there, you got to bail. Just to say you did, even though you’re going down. And that’s how I feel about global warming, and I don’t approve of this sort of “woe is me” attitude. There’s a hundred reasons for it. One of them is called denial. One of them is called self-preservation and avoiding despair. But I’d rather say, let’s roll up our sleeves and see what we can do here, guys.

AVC: Did the years of trying these different outlets for your work, whether it’s directly through activism [Fessenden founded an environmental site, Disconnex] or whether it’s through writing for radio and everything else you’ve done, did it change where your head was at when you returned to directing after six years since Beneath? Because Depraved feels like the work of a guy that’s in a different headspace at this point than your last couple of features. There’s an evolution to your direction.

LF: Well, that’s cool. I’d like to believe I am maturing. Honestly, part of the problem with Depraved is I really, really insisted I had to get it out of my skin, out of my hair, before I could move on. It’s been a bit of a bugaboo, to be honest. Everyone was like, “Well, you have all those other scripts, why aren’t you pushing them?” I’m like, “No, I just got to get this one out!”

You know, I played saxophone in a band and I helped people do music, and I do this and that—and my point is, to me, all the arts are sort of the same, and the political aspect is the same. It’s more about problem-solving. The real question is, how do you make a society work? That, I find a wonderful question. You know, you have to address that when you’re on a set. I always discuss this with my people. Do you rule by fear or by love? I love that question, because it resonates outwards. And obviously we’re dealing with that in the political spectrum right now. Do you make everybody feel uplifted and like they’re participating? If so, therefore, you build a great little society for 30 days when you’re making a movie. To me, it’s the same thing. I don’t really know that it’s different.

Obviously, there are tyrannical directors who are mean and they make good work, and that’s fine. But I always believe that it’s all integrated. So I have an obligation to create an atmosphere so people can flourish and see if they can pull their shit together. To me, it’s all about living. I’m trying to live right. I’m not saying I’ve achieved any of this, I’m saying those are the goals, that’s the conversation, and then you take note of how much you’re failing at it. [Laughs]

AVC: The arguments that people always make of, “Oh, sometimes to make something great, you’ve really got to be a dick and crack heads” or whatever, always seemed to be a very sort of Wall Street mentality. The idea that you don’t care about treating people with respect because something else is important at the moment—it’s like, do you really think they can’t go hand in hand?

LF: Absolutely dude. And it’s because the journey is the whole point. In other words, you don’t even know if you’re going to get to the fucking finish line. You don’t know if your movie will be seen. So all the suffering—you see people lay waste to the location, leave trash and garbage, being jerks, saying, “We’re too busy, we’re making a movie! This is the most important thing! Soon we’ll be at the Oscars!” And you’re like, “Yeah, but what if none of that happens? Then all you’ve done is just fucking made a mess here and acted like an asshole, so get your shit together! You can do both things at once!”

AVC: At this point, you’ve been doing this long enough, you’ve become a fairly ubiquitous character actor for a lot of people. What is the thing you find you get recognized for the most these days?

LF: Oh well, it’s a funny question, because the answer is Until Dawn. Can you imagine? I went to Comic-Con one year after the game came out, and because I’m in it for a minute and a half as a flamethrower guy, I actually felt famous for a brief second. It was absurd! I’m like, “Listen, kid—have you seen my picture Wendigo” He’s like, “What are you talking about?” So unfortunately, it’s video games. Oh, and also Tim Heidecker’s movie [The Comedy]. I once posted about that, which I produced with Brent Kunkle and some others, and oh my god, all the likes I got made me feel very small when I’m just tweeting about myself. So there you go. That’s when you learn how totally meaningless you are.