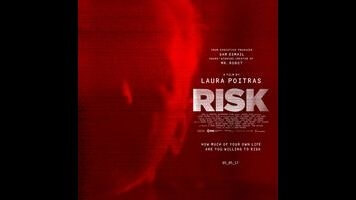

Based on the fact that its timeline of events stretches all the way to the first month of the Trump administration, Risk appears to have been in the editing room until very recently. It’s a patchy and seemingly unfinished film. It has two modes. The first is something like a Don’t Look Back of modern cloak-and-dagger activism, capturing Assange as he attempts to make a phone call to Hillary Clinton, dons a spy-movie disguise (complete with hair dye, false piercings, and colored contacts) to evade possible extradition to Sweden, and expounds about the “tawdry radical feminist” conspiracy against him to a room full of female supporters. This sort of verité skullduggery is Poitras’ forte, and her camera has a way of finding paranoid angles—shots framed through glasses of water, reflections split in double-hung windows, silhouettes in privacy glass. The second mode is a mea culpa that raises more questions about Poitras’ own ethics than it answers about the circumstances behind the making of the film and implicates the documentarian more than it exonerates her. There are times when one wonders whether she should have simply buried the film (or given the footage to another filmmaker) instead of attempting this unconvincing salvage job. In one pull-quote ready voice-over, supposedly drawn from Poitras’ journal, she declares: “I thought I could ignore the contradictions. I thought they were not part of the story. I was so wrong. They’re becoming the story.” But self-exegesis is not Poitras’ strong suit.

When a camera gets involved, impartiality goes out the door. At its most engaging, Poitras’ style is based on fascination with characters like Assange and Appelbaum and with the secretive spaces they inhabit. Her essayistic attempts to interrogate the project itself, however, are flimsy, fitful, and sometimes just intellectually dishonest. But here it is necessary to draw a distinction between documentary and document—because as a documentary, Risk is a failure, but as a document of the cause Poitras became too deeply invested in, it’s fascinating and involuntarily insightful. It is not a warts-and-all portrait. (In fact, it might be the first documentary in which acne has been digitally blurred off of someone’s face. Nice try.) Out of all the moments of real-life cringe comedy featured in the present version of Risk—whether it’s Appelbaum making an AIDS joke to an audience of female Muslim hackers in hijabs or Assange putting on a bad one-man show of paranoia during a conversation in a private park—the one that sticks is a painful interview with the WikiLeaks head honcho conducted by Lady Gaga (of all people) at the Ecuadorian embassy where he has lived since 2012. The scene plays like a reversal of the infamous meeting between Donovan and Dylan in Don’t Look Back, as the pop star remarks that Assange’s messy private quarters look like a dorm and then proceeds to interrupt every one of his deliberate, long-winded answers.

Risk asks haltingly whether it’s possible to separate a set of ideals from its most prominent spokespeople and their not-so-privately held beliefs, but never musters a conclusive stance on the question. But in the Lady Gaga interview sequence, it hints at how organizations that are ostensibly against tyranny can enable unchecked egos. Once you represent an ideal, there will always be someone ready to listen and nod—provided they aren’t more famous than you.